An Exhibit on Fashion and Ritual in Colonial Latin America Weaves Lessons Through Textiles

Step back 300 years into colonial Latin America and the textiles are lavish, fashions often akin to couture, and who wore what was determined not just by what they could afford, but by class and race, too.

It’s a setting the exhibit “Painted Cloth: Fashion and Ritual in Colonial Latin America,” opening Aug. 14 at the Blanton Museum of Art in Austin, Texas, will surround its visitors with.

More from WWD

Inside 'Another Justice: Us Is Them' at the Parrish Art Museum

"Diego Rivera's America" at San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

A Look at the Grand Reopening Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego

Through garments, textiles, paintings and sculpture, this trip to 1700s Latin America (the last full century of Spain’s colonial reign in the region; it ended in the 1820s after more than 300 years) is an opportunity to revisit and revise a narrative shaped by colonial rule, and to understand the meaning of fabric and garments in life and religion during the period. With Indigenous groups, enslaved Africans, Spanish colonizers and their mixed-raced descendants intermingling in one form or another, it’s impossible for the story of fashion in the region to be told through Spain’s lens alone.

“Fashion provided agency for all social sectors both in terms of race and class, and despite the goal of the Spanish authorities, who tried to restrict certain garments to specific social sectors, fashion was, as it is today, very fluid,” Dr. Rosario I. Granados, Marilynn Thoma Associate Curator of Art of the Spanish Americas for the Blanton Museum, says. “You can wear things to be perceived in the ways you want to be perceived and that was very much what happened in the colonial period. And I think it’s important because maybe that same conversation about how fashion allows you to navigate from different periods is something that [could help us] start having a conversation about race. Just as gender is very fluid, why don’t we accept that race is also very fluid, that your skin color says something about you but doesn’t limit you to what you need to be?”

The exhibition unfolds in five sections: “Cloth Making,” “Wearing Social Status,” “Dressing the Sacred,” “The Holiness of Cloth” and “Ritual Garments.” Pieces are culled from Mexico, Peru, Bolivia, Guatemala, Venezuela and the American Southwest.

Not ignoring the conflict of highlighting a period that was the foundation of so many still-standing societal inequities in all places that experienced colonial rule, Granados writes in the exhibit’s accompanying catalogue that those living under Spanish rule — and bending those rules where dress was concerned — found ways to use fashion “to deceive the system and turn it into their best interests.”

photo © Museum Associates/ LAC

Citing historian Tamara Walker, who wrote in her own research that enslaved Africans were able to find their own agency by traversing the streets of Lima “prominently in Spaniards’ sartorial elegance,” which gave a nod to their masters’ status, Granados says the “Wearing Social Status” section of the exhibit shows Indigenous groups and those of mixed-race in other parts of Latin America also found ways to use fashion to navigate life.

“In this way, fashion uniquely showcases how colonialism as well as agency were exercised in everyday life,” Granados writes, adding, “It offers a better understanding of the social fabric that led to the very need for sovereignty.”

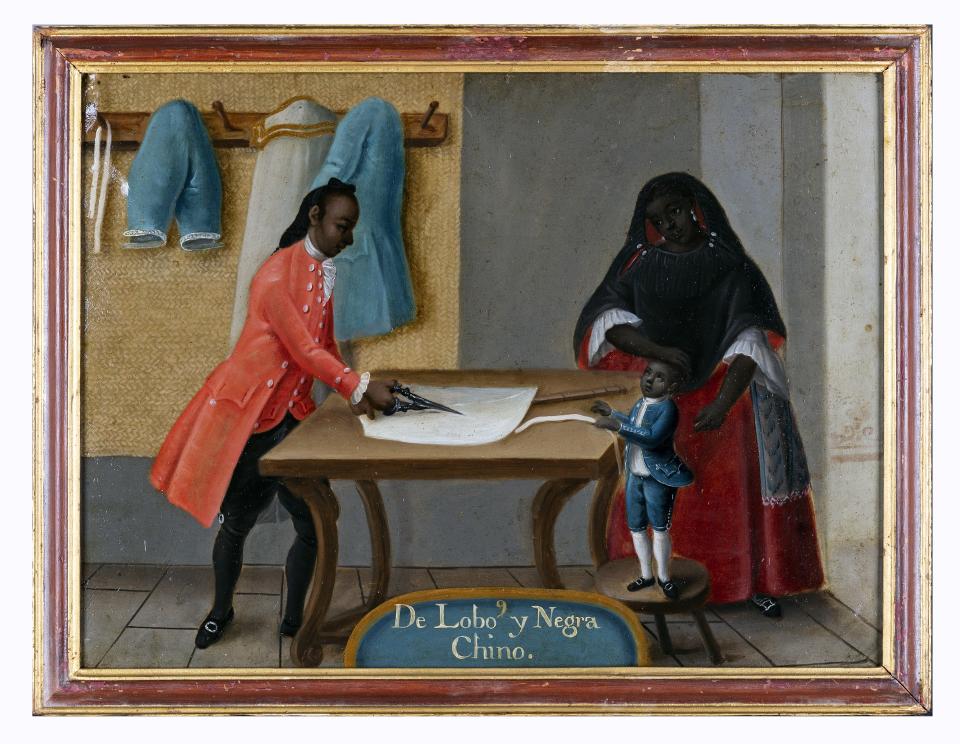

Rules dictated that certain races in particular should wear certain garments so the authorities could retain social and economic control over them.

A 1582 ordinance in Mexico City, for one, ruled that women who were not Indigenous could not wear traditional Indigenous clothing, like the tunic-like huipil and cueitl, a wrap skirt (which would have gotten them out of certain taxes the protected Indigenous populations weren’t liable for, among other freedoms).

What’s perhaps a full-circle moment with today, where artisanal and traditionally made garments are more widely appreciated (if not trendy), Indigenous garments were a status symbol during colonial rule (which Granados admits could have been considered colonial-era cultural appropriation).

Javier Rodriguez Barrera

Non-Indigenous common women were expected to dress in the Spanish style, with an asayo (skirt), a blouse, a rebozo (shawl) and a tapapiés (underskirt). Black women often covered their heads and upper bodies with the tapapiés. Women with greater means might have a corset tied at the front of their blouse, nodding to the influence of French fashion. Indigenous male “commoners” wore straw hats, while nobility wore felt hats. And on and on went the distinctions.

“Each group was supposed to wear specific things so they could be recognized,” Granados says. “The Spanish crown was very worried about how people were just mixing because it was not possible to tax them correctly because it was a problem of identifying in which box each [group of] people was, as it is today and as it is always. And I think this is a big difference to understand how colonialism worked differently in the Americas versus in the United States or India or any other colonial environment.”

Some of these dress distinctions will be visible in the casta paintings on display at the exhibit. These paintings, intended to represent “an ideal version of what colonial society was,” according to Granados, depict different people with different ethnicities and wearing different fashions engaged in various activities corresponding to their class or caste, hence the genre’s name (e.g., nobility doing nothing, working class engaged in commerce). A series of similar-style pieces from Peru will be on display in the U.S. for the very first time at Blanton.

As these various ethnic groups continued to mix, and with Mexico City in particular a center for trade, so did the region’s textiles — which visitors to the exhibition will be able to see, including a set of silk swatches from Mexico sent with official reports to the king of Spain — take on new traits and characteristics.

“Traditional uncus, for instance, those tunics that were made in Peru that were so important for the Inca that were made with wool, they started to be made in cotton with silk embroidery. The huipiles that were made with cotton, they started to be made with silk. Also, the dyes were different. Silk was dyed with local insects, the cochineal [a red-hued insect], for instance. So there was a constant influence between each other,” Granados explains. “We’re going to have in the show a painting of an Indigenous cacique, or leader, that is wearing a huipil, the very traditional women’s attire, and it’s embroidered with an eagle…that’s a [Spanish] royal insignia, so there was constant influence.”

There, again, is the often-contentious line between cultural influence and appropriation. But this exhibit isn’t about digging into that controversy, rather educating to enlighten.

What Granados wants visitors to take away from the exhibit is a deeper understanding of the various influences on fashion and dress during colonial rule, which was by no means solely dictated by the colonizers. She also wants the industry to better grasp Indigenous groups’ contribution to fashion and textiles in the region, which remains a thriving industry today — not a niche to be noted only when a European luxury designer appropriates it for the runway.

“These textile traditions have been changing constantly, but they were very much alive in the colonial period as much as they continue to be today,” she says. “[The exhibit] will also bring the conversation to what the colonial experience in Latin America actually was.”

It’s about visibility, and adding to fashion’s canon what has long been omitted in favor of Euro-centric narratives.

Courtesy Blanton Museum of Art

Among the curator’s favorite pieces? A woman’s anacu (dress) made of camelid (a member of the camel family) fiber and cotton with embroidered edge stitching from the late 16th century, and a silk and cotton rebozo from the late 18th century. Of the latter, Granados says, “It was not an object to be worn every day but it has images of [Mexico City] and I think it is very interesting how this particular rebozo, and also other ones that do that as well, they were used as objects to show the pride of Mexico City at the center of many influences, and you can see the embroidered figures are showing European and Indigenous fashion.”

The “Painted Cloth” exhibition runs at the Blanton from Aug. 14 through Jan. 8, 2023. The accompanying coffee-table book of the same name, with deeper context for those who want to dig in, is available for preorder via the University of Texas Press and will be released in line with the exhibit. On Oct. 21, an adjacent symposium (via Zoom), “The Fabric of the Spanish Americas,” will bring together scholars from across the Americas and the U.K. to continue the exploration of the social role textile arts played in colonial Latin America.

“I really hope it is just the starting of a larger and more meaningful conversation,” Granados says.

Best of WWD

Sign up for WWD's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.