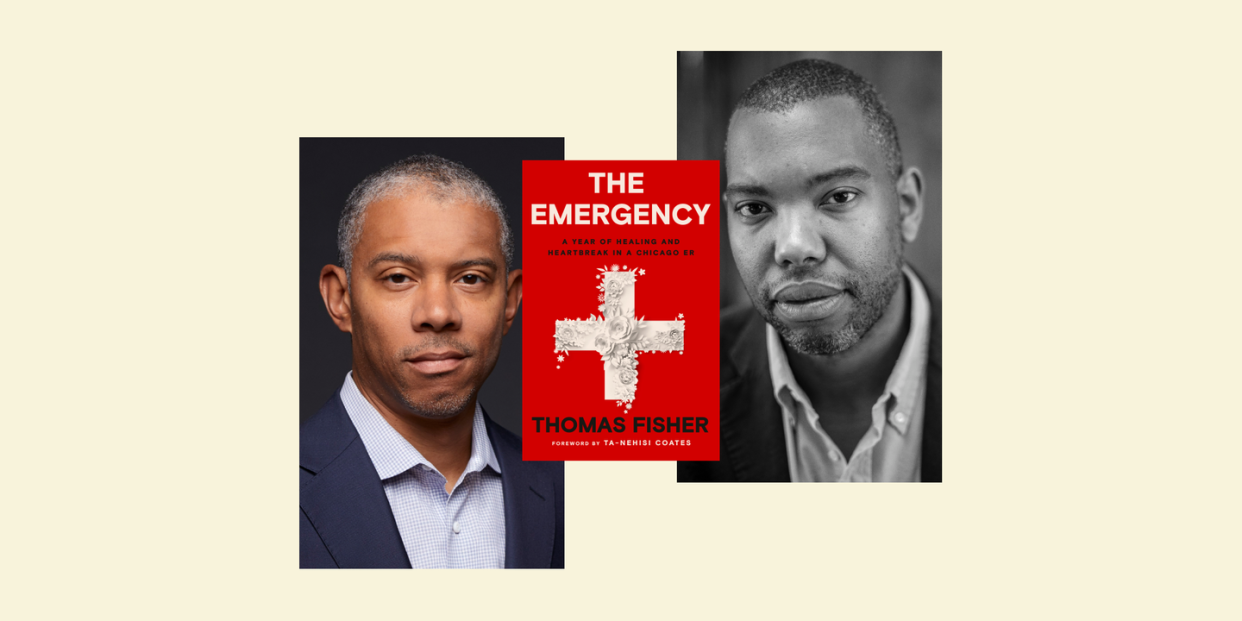

Exclusive: Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Foreword for The Emergency, by Thomas Fisher

“Tom is a direct observer,” writes Ta-Nehisi Coates, a MacArthur “genius” fellow whose novel The Water Dancer was a 2019 Oprah Book Club pick, in his foreword to Thomas Fisher’s galvanizing The Emergency: A Year of Healing and Heartbreak in a Chicago ER, excerpted exclusively at Oprah Daily. “He has seen the machine from every possible vantage—as a doctor operating within it, as a public health scholar studying it.” These two activists have known each other since college, and while they’ve pursued different career trajectories—Coates as an essayist, a journalist, and a novelist, and Fisher on the front lines of medicine—both have devoted their lives, fortunes, and sacred honor to an ever more inclusive and equitable America, elevating those marginalized by race, poverty, and geography. Here Coates eloquently highlights why Fisher remains both a personal inspiration and an essential voice in our healthcare crisis, revealing how the powerful divide and conquer according to caste. “The residents of the South Side who Tom cares for are ostensible participants in the American social contract—its edicts and its bounty,” Coates observes. “But the former land harder on them than the latter.” At a moment in which the Covid pandemic has disproportionately ravaged Black and Latino communities, knocking off three years of life expectancy—triple the level of whites—his words, and Fisher’s searching book, are calls to arms. —Hamilton Cain, contributing editor at Oprah Daily

Foreword by Ta-Nehisi Coates

ONE EVENING IN 2005, I drove over to see an old friend and classmate in the Bronzeville section of Chicago. Natalie Moore—“Big Nat,” as we called her—had attended Howard with me and worked on the school newspaper. As young journalists, we had probably planned an evening of catching up and comparing craft notes. But there wasn’t much craft discussed that evening, if only to keep from boring Big Nat’s other guest: Thomas “Tom” Fisher. Tom and Nat had both grown up on the South Side and had been friends since childhood. I’d met Tom at Howard, where he would occasionally visit Nat. Beyond a love of food, drink, and crude jokes, what the three of us shared was a deep sense that our work must serve our community. For Nat and me, that responsibility manifested itself in our approach to journalism—the stories we told, the people we highlighted, the arguments we advanced. But for Tom, who’d just finished his residency in emergency medicine, that responsibility was always more direct. I remember how we commiserated over takeout and libations.

I remember the “oh my people” jokes we made as music videos scrolled across the screen. But more than anything that happened in that apartment that night, I remember what happened outside it. When I’d first arrived hours earlier, I’d seen a group of young brothers seated on the stoop across from Nat’s apartment. They were having a party of their own. I pulled up, got out of my car, nodded the silent greeting of Black people the world over, and kept it moving. A few hours later, we heard gunshots. There was almost no alarm among us, save for the collective note that the shots seemed rather close. But we kept the party going until we saw police lights strobing through the windows. It was time to leave anyway. When Tom and I stepped outside, what we saw in the streets of Bronzeville was no great shock to either of us—police tape on the sidewalk, the body of a young Black man laid out on the concrete—but the moment is still indelible for me. And whatever weight it put on me, I knew even then, did not compare to what Tom would have to carry.

It was not merely that Tom was an ER doctor directly caring for those affected by the plague of gun violence that covered the country and levied a particular toll on Black neighborhoods. It was that those bodies were rushed into the ER from the streets that Tom called home. He was working not just for the Black community in general but for the same South Side of Chicago where his parents had settled and where he had been raised; he was caring for the lives and bodies of his neighbors. I don’t think it’s too much to say that the lion’s share of Tom’s professional life has been consumed not only by treating the kind of violence we bore witness to that evening, but by an urgent attempt to understand why that violence tends to fall with such weight on the South Sides of America while barely grazing its Gold Coasts. It is those two labors that fill the pages of The Emergency: the work of Dr. Fisher’s hands, treating patients in the midst of a pandemic, and the work of his mind, trying to understand the larger system that delivers so many broken bodies from these streets into his care.

The answers he arrives at are not comforting. African Americans rank at the bottom of virtually every socioeconomic indicator. Healthcare is no exception. Explanations for this tend to focus on individual behavior. Confronted with the shocking death rates befalling Black people in the wake of Covid-19, Surgeon General Jerome Adams asserted that the Black community needed to “step up” and “avoid alcohol, tobacco, and drugs.” “Do it for your Big Momma,” Adams asserted. “Do it for your Pop-Pop.” There is no data that shows Black people drinking, smoking, or drugging more than anyone else (and some that indicates they do so less.) But the point is comfort, not data. And it is simply more comforting to believe that the disproportionate impact of the worst pandemic in American history could have been avoided if Black people were monastic.

But The Emergency joins a disturbing consensus increasingly being reached in the scholarship of power—the vast chasms between the haves and have-nots of America are rarely benign mistakes amenable to behavioralism. The work of Ira Katznelson, Beryl Satter, and Richard Rothstein has demonstrated that the yawning wealth gap is the result not of poor spending habits but of federal policy. Eve Ewing’s research into Chicago’s schools shows how “school reform” in Black communities ultimately destroyed the last outposts of the state, short of law enforcement. Devah Pager’s studies of employment and incarceration show that employers evaluated Black men with no criminal record the same as white men with a criminal record. Moreover, this scholarship has demonstrated that the relationship between the powerful and the powerless is parasitic. The historian Edmund Morgan does not merely condemn American slavery but demonstrates how American notions of freedom depended upon it.

This is the tradition out of which The Emergency emerges. What it shows is that the healthcare chasm is not an accident but a feature of white supremacy and American capitalism. But unlike the journalists, sociologists, and historians who must painstakingly recreate events and power dynamics from archives and interviews, Tom is a direct observer. He has seen the machine from every possible vantage—as a doctor operating within it, as a public health scholar studying it, as a White House fellow working to shape policy, and as healthcare leader trying to implement that policy. He comes to understand that long wait times in ERs like his on the South Side cost lives and allow for the spread of misery; that those wait times differ drastically from those in hospitals mere miles away; that the misery in one ER and the satisfaction in another are linked. He shows how even within a hospital ostensibly serving a poorer and blacker clientele, the relentless laws of capitalism lead the hospital to consider erecting a system of de facto Jim Crow healthcare.

To demonstrate this, Tom unearths a factor that those in power seek so often to obscure: the state. It is a trick of members of the corporate class and their followers to depict their success as the correct outcome of a working market. But The Emergency shows how that enterprise is subsidized by the state— doctor training funded by the public, research underwritten by government grants, patients insured by government programs. And despite the public subsidization of healthcare, the public benefits vary according to class. The residents of the South Side who Tom cares for are ostensible participants in the American social contract—its edicts and its bounty. But the former land harder on them than the latter. And despite being a part of the public that subsidizes health care, they do not get their fair share of the returns.

The Emergency renders the impact of this capricious system in visceral detail. Pain and agony are everywhere, but a look at the system through a doctor’s eyes reveals that Black people do not merely live shorter lives than their peers; their lives are more physically agonizing. And this is not just the agony of illness and injury, but the compounding of that illness and injury by the sheer fact of racism. “Your body, like many bodies on the South Side, began accumulating injury and illness before the bodies of your peers on the North Side,” Tom writes to a patient. “And unlike your peers, you had fewer chances to recover and return to your prior health.”

Through it all, the author moves like a blur, going from patient to patient doing his best to heal the body, “our most important endowment.” He almost always comes up short. And that is because even as a doctor, he is merely an actor within the system, not its author. And at the climax of The Emergency, the system reaches out to touch not just Tom’s neighbors but his family. The Emergency is not just a year in the life of an ER during Covid but a powerful examination of the entire complex of healthcare and the inequalities that bend it. It is worth remembering the early days of Covid’s arrival, when it was said to be “colorblind.” Maybe we wanted to believe that in a true crisis we would find ourselves together, on even footing, if only in our common human frailty. But now here we are, two years later, with Blacks and Latinos having lost some three years of life expectancy over the course of the pandemic—triple that of whites. We should have known better. We should now know better.

The Emergency explains why, be it the plague of gun violence or the plague of Covid, the burden is never borne equally.

From the book The Emergency, by Thomas Fisher. Copyright © 2022 by Thomas Fisher. Reprinted by arrangement with One World, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

You Might Also Like