Everything You Need to Know About Ulcerative Colitis

“Hearst Magazines and Verizon Media may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below.”

Table of Contents

Overview | Causes | Symptoms | Diagnosis | Treatment | Complications | Prevention

What is ulcerative colitis?

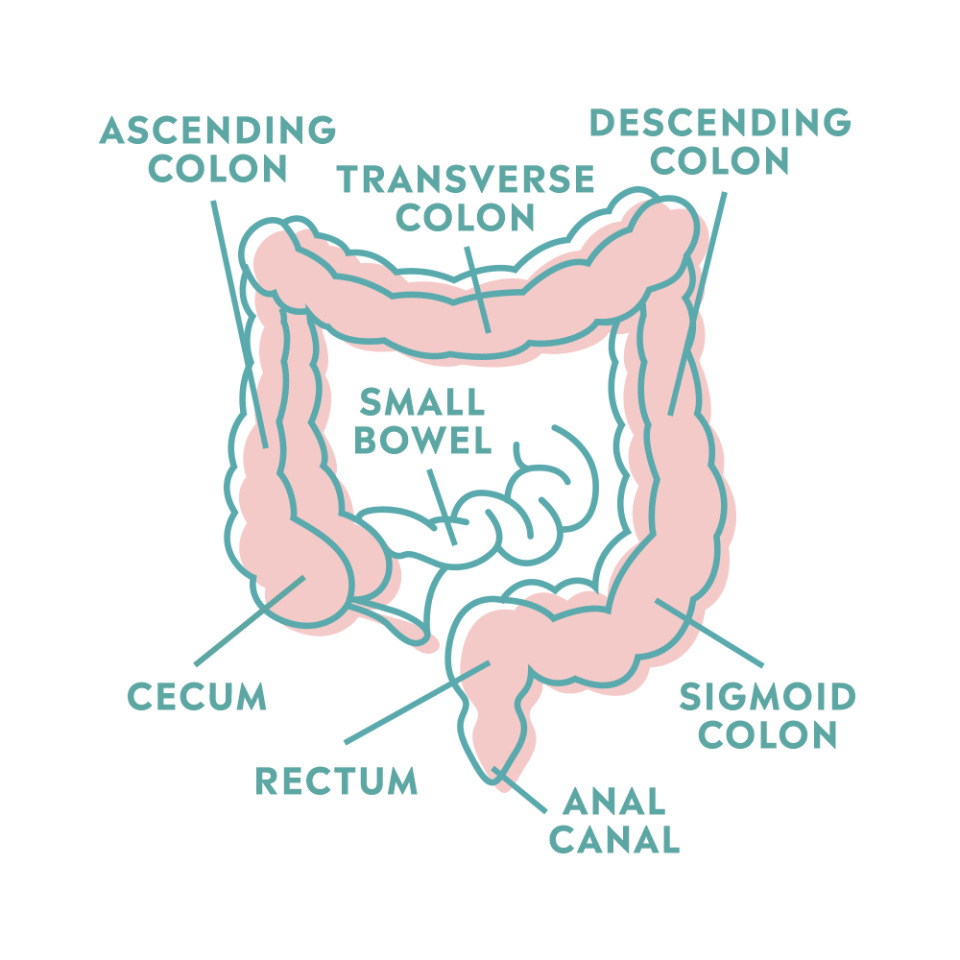

Ulcerative colitis (UC), which affects between 600,000 and 900,000 Americans, is a type of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) characterized by chronic inflammation that typically impacts the rectum and sometimes, other parts of the colon. It’s considered a superficial condition because it does not impact deep tissues and does not affect other parts of the digestive system. That makes it different from Crohn’s disease (another type of IBD that it’s often confused with), in which inflammation can occur anywhere within the digestive system and can extend deep into the tissue.

Ulcerative colitis can cause abdominal pain, diarrhea, blood, or mucus in the stool, as well as rectal bleeding and bowel urgency (a strong need to defecate). These symptoms often develop over time and can wax and wane. Alternatively, they may worsen over time or improve and go away.

[1,2,3]

What are the types of ulcerative colitis?

The different types of ulcerative colitis are defined by the location of the inflammation, explains Aja McCutchen, MD, a gastroenterologist at Atlanta Gastroenterology Associates. The four types of UC are:

[3,4]

What are the causes and risk factors of ulcerative colitis?

It’s still unclear exactly what causes ulcerative colitis. It’s thought that it occurs when the immune system malfunctions and attacks healthy cells in the digestive tract. [1] This change in immune function may be caused by imbalances in the gut microbiome, the bacteria that naturally live in our digestive system, Dr. McCutchen says. If the microbiome is off-balance, the intestinal barrier may allow particles to pass through it more easily. When that happens, it can mess with the mechanisms needed for maintaining a well-functioning immune system, she explains.

Whatever the cause, some factors appear to make certain people more likely to develop UC. These risk factors are:

Family history. People with a close relative (a parent, sibling, or child) with UC or other types of IBD are more likely to have ulcerative colitis. [1]

Age. There tends to be a peak in diagnoses in people ages 15 to 30 as well as those ages 50 to 70, Dr. McCutchen says. If you are genetically predisposed to UC, certain bodily changes that occur as you grow may cause the condition to develop. It’s unclear why older adults also get UC in higher numbers. It may have to do with exposure to antibiotics, Dr. McCutchen says. Additionally, the immune system weakens with age. [5]

Race or ethnicity. While anyone can develop UC, Caucasian people are more likely to develop UC compared to other races, and people of Ashkenazi Jewish descent are at the highest risk. It’s unclear what’s behind these differences. [1]

What are the symptoms of ulcerative colitis?

Most symptoms of ulcerative colitis involve the digestive system. Symptoms include:

If you notice any bleeding or blood in your stool, see a gastroenterologist, Dr. McCutchen recommends. Symptoms tend to be somewhat progressive and then may get better and then worse again, she adds. “However, most patients say they see a change in their bowel habits and know something is going on,” she says.

[1,6]

How is ulcerative colitis diagnosed?

The first step to diagnosing ulcerative colitis is to go over your medical and family history with your doctor. “Also, be prepared to discuss when you first noticed more frequent bowel movements or changes from your typical bowel movements,” Dr. McCutchen says. Keep in mind that symptoms can ebb and flow, so what you thought was a stomach bug might actually have been the first signs of UC. And when thinking about family history, “consider any inflammatory bowel disease, including UC but also Crohn’s disease,” Dr. McCutchen says.

After reviewing your history and conducting a physical exam, your gastroenterologist will likely do some tests, including: [7]

Blood work. This can test for UC, anemia (low red blood cell count, a common side effect of UC), and other infections or digestive conditions.

Stool tests. Doctors can examine a stool sample to check that there are no other infections or parasites that may be responsible for your symptoms.

Colonoscopy. This is the “gold standard” to diagnose UC, Dr. McCutchen says. You first consume a solution to clean out your colon. Then, while you’re under anesthesia, a doctor will insert a thin tube with a light and camera at one end to examine the colon and typically the small intestine and look for inflammation. The doctor may also take a small sample of colon tissue (a biopsy) to examine under a microscope and look for signs of UC.

The risk of complications with any of these tests is rare, Dr. McCutchen says. “If you have a biopsy and have an inflamed colon, you may have some post-op bleeding, but the risk is low,” she adds.

Ulcerative colitis treatment

Medication is the first line of treatment for ulcerative colitis; if that doesn’t help, surgery may be necessary. “The first goal of treatment is to get the patient into remission where they’re not having a lot of flare-ups—a worsening or return of symptoms,” Dr. McCutchen says. The second goal, she adds, is to see healing of the lining of the rectum and colon when examined internally during a colonoscopy.

Medications

“Most medications aim to decrease the inflammatory response in the intestines,” Dr. McCutchen explains. The exact medication depends on where the disease is located and how severe the inflammation is, she adds. Options include: [8, 9, 10]

Aminosalicylates. Most often used in mild to moderate cases, these work in the intestines to decrease inflammation. These medicines are given rectally and/or orally depending on where the inflammation is located.

Corticosteroids. Used in moderate to severe cases of UC, steroids also reduce inflammation.

Biologics. Made of protein, sugars, nucleic acid, or a combination, [11] biological medications alter the immune system response so that it stops promoting inflammation.

Surgery

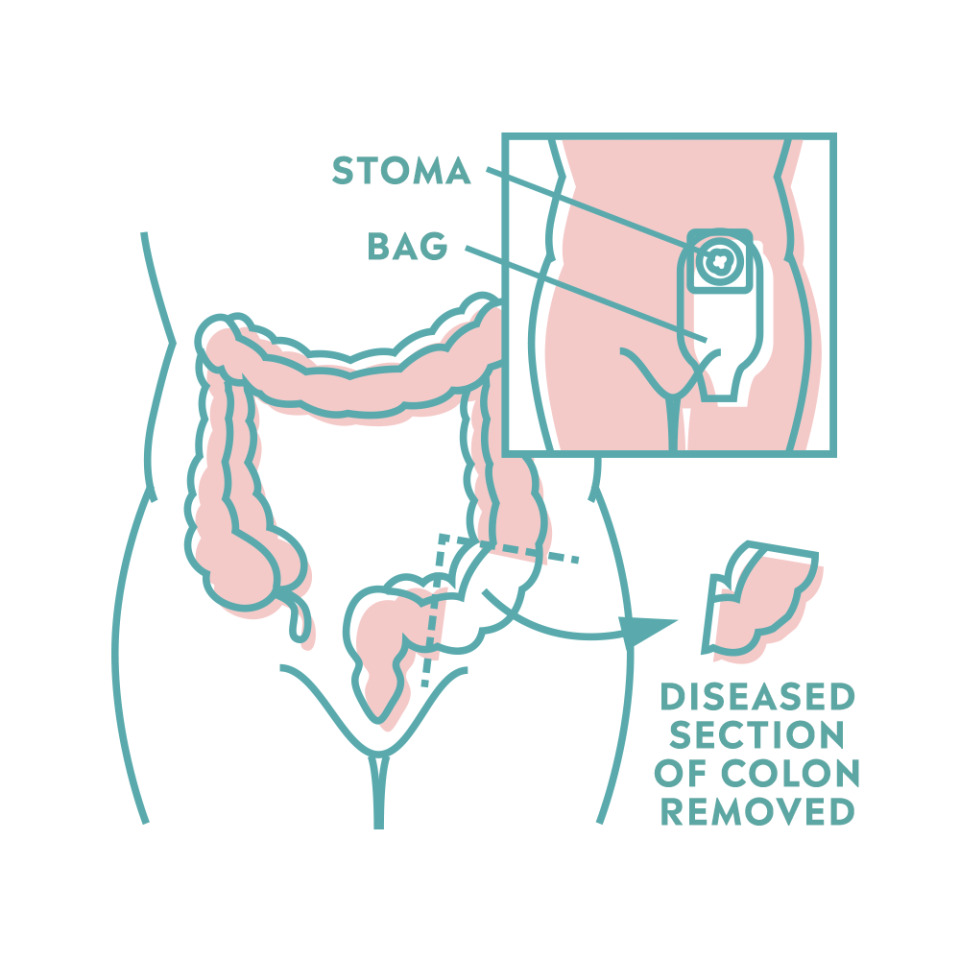

If medications don’t work, it may be necessary to remove the colon and rectum. “You can live without a colon or rectum, but this is a last resort,” Dr. McCutchen says. Two types of surgery for ulcerative colitis exist: [9, 10]

Ileoanal reservoir (J-pouch) surgery: After removing the colon and sometimes the rectum as well, surgeons will create a pouch from the end of the small intestine. Then they attach the pouch to the anus. With this surgery, you can have normal bowel movements though they will likely be more frequent.

Ileostomy: In this instance, after removing the colon and the rectum, or parts of the small intestine, surgeons attach the end of the small intestine to an opening they create in the abdomen (called a stoma). An ostomy pouch attaches to the stoma and collects waste from the small intestine. You empty the ostomy pouch as it constantly fills throughout the day rather than having bowel movements.

[9,10]

Complications of ulcerative colitis

Ulcerative colitis can lead to other problems, including:

Anemia. The loss of blood can lead to this reduction in red blood cell count, Dr. McCutchen explains.

Colorectal cancer. This is particularly a risk for anyone whose UC has progressed beyond ulcerative proctitis. The risk also increases after having UC for eight years, Dr. McCutchen says. Gastroenterologists typically perform annual colonoscopies and surveillance biopsies to screen for colorectal cancer, she adds.

Toxic megacolon. This rare complication of severe colon disease causes swelling, severe stomach pain, fever, increased heart rate, and diarrhea. Call your healthcare provider if you notice any of these symptoms. If left untreated, toxic megacolon can be life-threatening. [12]

Liver disease. If UC isn’t properly controlled, the liver can also become inflamed. This can lead to liver conditions such as fatty liver disease, hepatitis, gallstones, and inflammation of the bile duct system. [13]

Low bone mass or joint problems. Long-term use of steroids to treat UC can lead to bone and joint issues. [4]

A hole in the wall of the large intestine (called a perforation). [4] If this happens, you’ll need emergency surgery to remove the colon, Dr. McCutchen says. As with the surgeries above, after this, you may or may not need a pouch to collect your stool.

How to prevent ulcerative colitis

Unfortunately, there’s no way to prevent ulcerative colitis. The best thing anyone with UC can do is work to prevent flare-ups making lifestyle changes:

Dietary changes. Most nutrient absorption occurs in the small intestine, which doesn’t play a role in UC, so there’s no universal diet for this condition, Dr. McCutchen says. It can help to keep a food journal so you can note when flare-ups happen. You may notice that certain foods, such as those high in fiber, sugars, or fats, exacerbate your symptoms. Discuss any dietary changes with your healthcare provider or a registered dietitian experienced at working with people who have UC. [14]

Stress management. Stress also appears to increase the likelihood of flare-ups. [15] “I really encourage IBD patients to see a therapist or mental health provider who is versed in IBD and can help them manage their symptoms,” Dr. McCutchen says. Additionally, things like yoga, [16] regular exercise, [17], and mindfulness practices [18] (like meditation) may help manage the symptoms of ulcerative colitis.

Medication changes. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (ibuprofen, naproxen, etc.) can cause flare-ups. Ask your doctor about alternative options for pain management when needed. [19]

References

[1] https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/ulcerative-colitis/symptoms-causes/syc-20353326

[2] https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/10351-ulcerative-colitis

[3] https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/digestive-diseases/ulcerative-colitis/definition-facts

[4] https://www.atlantagastro.com/provider/aja-s-mccutchen-md/

[5] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2914180/

[6] https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/digestive-diseases/ulcerative-colitis/symptoms-causes

[7] https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/digestive-diseases/ulcerative-colitis/diagnosis

[8] https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/ulcerative-colitis/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20353331

[9] https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/digestive-diseases/ulcerative-colitis/treatment

[10] https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/10351-ulcerative-colitis/management-and-treatment

[12] https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/toxic-megacolon

[13] https://www.crohnscolitisfoundation.org/sites/default/files/legacy/assets/pdfs/liver-disease.pdf

[14] https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/10351-ulcerative-colitis/prevention

[15] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6821654/

[16] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0022399919309195

[17] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6884387/

[18] https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-63168-4

[19] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4703528/

You Might Also Like