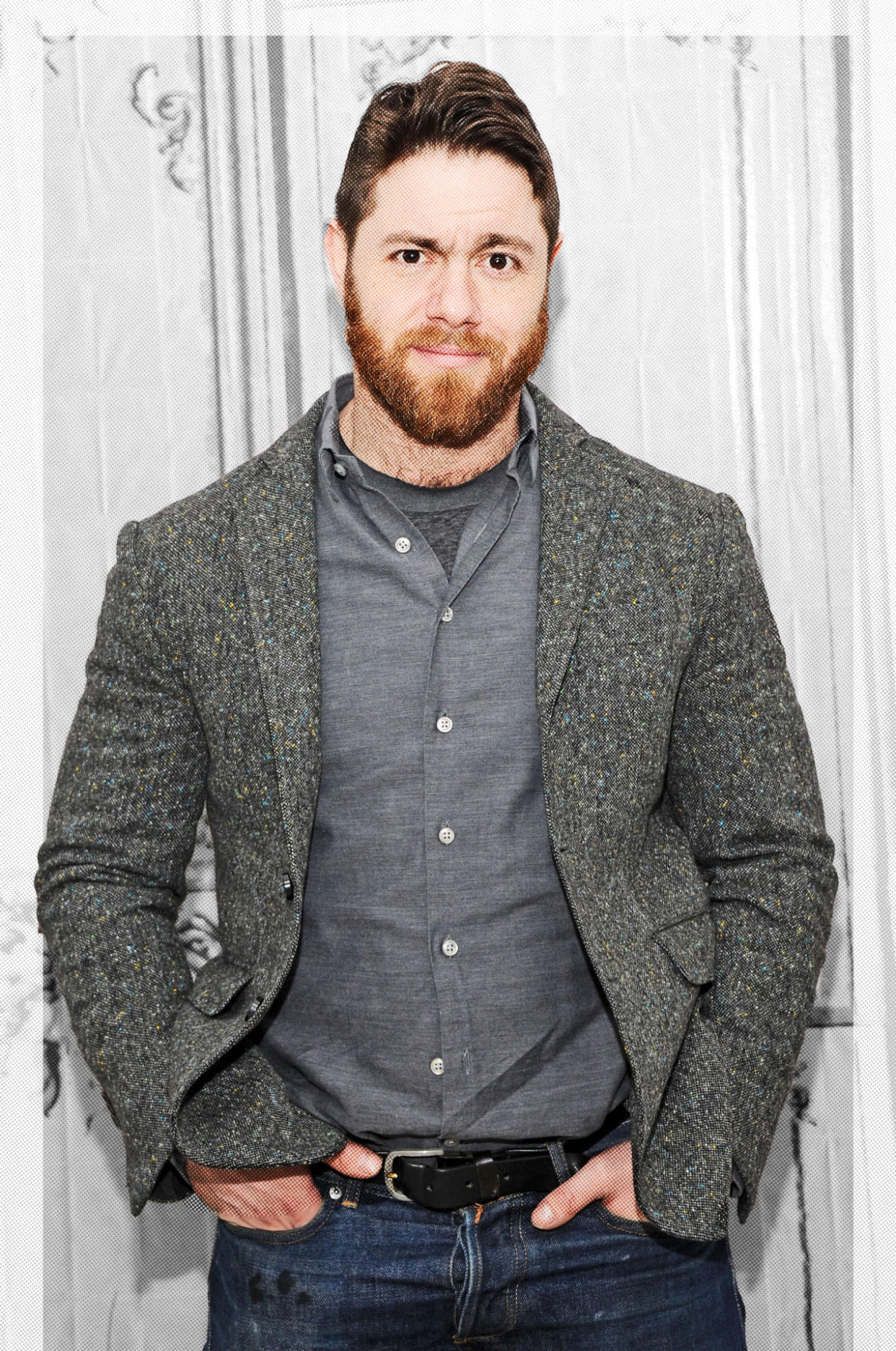

‘Everything Is Copy’: A Chat With Jacob Bernstein on His Mom, Nora Ephron, and His New Film About Her

Writer Jacob Bernstein at the premiere of his film Everything Is Copy. (Photo: Getty Images)

When Nora Ephron, acclaimed essayist, author of Heartburn, and writer-director of beloved classics like Sleepless in Seattle, You’ve Got Mail, and Julie and Julia, died in 2012, the news was shocking. Even those closest to her didn’t know she was ill. Now her son, New York Times writer Jacob Bernstein, has made his own film, Everything Is Copy (premiering March 21 on HBO), interviewing many of those closest to her (including his dad, Carl Bernstein, Mike Nichols, and Steven Spielberg) to unpack just what made Ephron such a magnetic figure.

Yahoo Style: Where did the idea for the documentary come from in the first place?

Jacob Bernstein: In the fall of 2012, one of my editors sent me to go interview Lisa Immordino Vreeland, who had just done the Diana Vreeland movie The Eye Has to Travel.

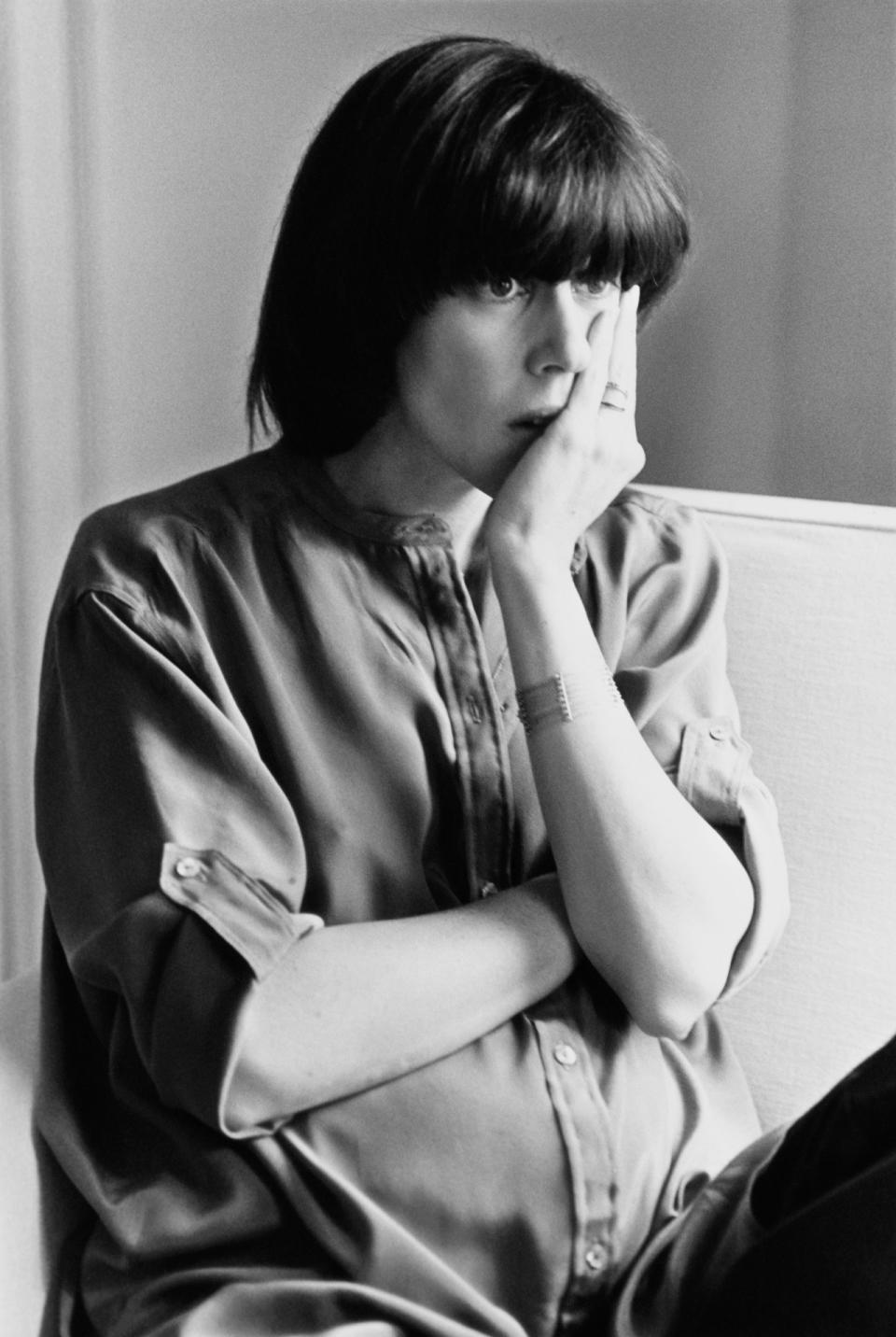

Nora Ephron in Boston in 1978. (Photo: Getty Images)

Right.

At the end of the interview I said to her, “What are you doing next?” She said, “Well, I might want to do a film … about Nora Ephron.” I said, “Well, I think there might be somebody in front of you [who could direct that].”

How did you find the documentary-making process to be once you were in it?

I loved talking to people about her. When she was about to die, I began to call her friends to say that she was shutting down and I described these conversations a little bit in the Times Magazine piece that I wrote about her.

I found it strangely beautiful, those conversations. Her death was a tremendously difficult and sad thing, but I found the act of reminiscing about her and listening to other people and how they processed her behavior really interesting and enlightening. I just wanted to keep doing it. The film afforded me that opportunity.

There were some remarks in the film that toward the end, even friends of hers, who weren’t privy to what was going on, sensed there was a marked shift in her temperament, in her openness, in her ability to say, “I love you. I miss you.” Did you feel like you experienced that, and in what way?

Yes. I think I did experience it, and at the same time I think that I was less aware of it than they were. In part because when it’s your parent or it’s your spouse and you live with them every day, you’re somehow less aware of the subtle shift in behavior than people who perhaps don’t see them as often. It’s almost like when your spouse gets fat and everybody else notices it before you do.

A candid photo of Nora Ephron for the HBO documentary Everything Is Copy. (Photo: courtesy of HBO)

There was also a real moment when you describe Nora’s mother, your grandmother, and how they had an interesting relationship in that your grandmother wasn’t necessarily the doting, warm mom anyone would hope to have. How was Nora herself as a mother to you and to your brother, Max?

Well, I think that my mother was warmer than her mother was to her, but my mother was not a person who coddled people either. I can’t pretend that she was. I think that would be a little … I think that would actually be the thing that would hurt her about all of this, that I can’t quite … I’m not convinced she was a totally different parent in that regard.

Was there any conversation that you and Max had about his involvement in this? Because —

Because he’s not in it.

Yeah, exactly. If I’m not mistaken, he’s not in it.

Yeah, we talked about it a bunch. I think that Max felt a number of things; the first is, he’s not a writer in the way that anybody else in our family is. He’s a musician, so he does write songs. I don’t think that the nature of confessionalism or memoirism, none of that is what he does or feels pulled toward doing. That’s fine. He’s entitled to that.

And of course your father, Carl Bernstein, who famously left your mother for another woman (something she then fictionalized with her novel Heartburn), must not have been keen to get onscreen to discuss it.

Yeah, he held off on being interviewed for a very long time. I think Max had a tough time squaring how he was going to honor my mother without somehow dishonoring my father. This wasn’t the thing that my dad wanted me to do. That was plain. My father has been in a lovely marriage for the last, I think, 10-ish years and they’re very happy. The idea of revisiting this divorce that had happened 30 years ago was not his idea of what he hoped would happen. I think he was particularly concerned about the nature of doing it on camera. Had I decided that I was going to write a book that was in some way a memoir, it would have been less daunting in some ways.

Nora Ephron with actresses Meryl Streep and Jane Lynch in 2009. (Photo: Getty Images)

How did you reconcile your own feelings of your creative output and what your father felt about the whole thing?

For a while we didn’t reconcile it. For a while I just went ahead and clubbed away at it and interviewed other people and hoped that he would come around. I didn’t reconcile it. I mean, how do you reconcile it? My father was not cooperating for quite a while. It was difficult and frustrating and, at the same time, weirdly understandable.

Bob Gottlieb, Nora’s editor at Random House, made a really interesting comment about her absolute need for success. What are your thoughts on that? Was that unsurprising to you?

I don’t think it’s inaccurate. No, I don’t, but I think I will say about my mother and her need for success that there are very few people who are as driven to succeed as she was who do it without making tremendous moral compromises. I think that part of what my mother never liked about the Clintons was that she saw them as people who always believed that the ends justified the means. I don’t think that she lived her life that way. She was so principled and angry and wrote about [her beliefs] in a way that you never could today.

Do you think she suffered repercussions for that?

No. I don’t really. I think she was witty enough and talented enough that there was always going to be a lot of work for her. That is another thing that I found sort of surprising in some way is that she was simpler in certain ways than I expected. I’d always kind of wondered how my mother had done as much as she did, and did she feel ambivalent to things that I didn’t have access to? Ultimately, I think the people who succeed in really huge ways are often able to do it because they don’t have a lot of sleeplessness about things.

I don’t think that she had a lot of sleeplessness about writing Heartburn. I don’t think she had a lot of sleeplessness about going after the people at Esquire. She didn’t get tied up in knots or hamstrung by ambivalence.

Nora Ephron in her home in 2010. (Photo: Getty Images)

About ambivalence, which is another point you touch on in the film: What do you think of the notion that she betrayed her early wit and journalistic sharpness with films that are beloved but not considered as weighty as her previous work? Do you think that bothered her at all?

I think that it bothered her, and I think she also felt that it was unfair and that the criticism missed certain things about the movies. For example, You’ve Got Mail is actually underneath this love story about two people who work together and hate each other and are secretly falling in love — you have this story that’s actually about gentrification and big business. Now, of course Barnes and Noble is doing horribly, but the neighborhood bookstore was actually driven out of business by Barnes and Noble, and then Barnes and Noble basically got driven out of business by Amazon. The point is that the film did have real subtext. Even Sleepless in Seattle, there is a satirical component to this boy who calls in a radio show. It’s absolutely about public confessionalism, right?

I never thought about that, but completely, yes.

I think that all of that was there, and I think that that upset her. At the same time, I think that there’s no question that she shifted in certain ways. I think that every creative person who starts their career in an edgier, angrier place disappoints his or her fans when he or she becomes less edgy and angry. I think it’s inevitable. It’s why we debate whether great rock stars can do their best work when they’re happy or when they’ve gotten married. Is misery the greatest tool of creation?

Jacob Bernstein speaking about his film Everything Is Copy. (Photo: Getty Images)

Do you have a favorite of her films?

Well, I actually like You’ve Got Mail quite a lot. I think When Harry Met Sally is … I understand why that’s the one that makes it on to the most lists and all of that, but I found You’ve Got Mail very sly and interesting. That might be my secret.

Now that your film is complete, how do you feel about the finished product? Is there anything you wish you could have done differently or put in something that was hard to let go of?

No, I think that what I hoped to put in there is in there. I certainly could have played with it longer. I felt letting it go was maybe the most difficult thing. I think having her on a monitor there for two years was a little bit like my two years of magical thinking. She was dead, yet there she was. Then the film was done and she was really gone. Lynn Hirschberg, who works at W and is one of my heroes as far as what a person can do covering culture and entertainment, said to me, “I think you’re going to have a difficult time with this being over.” She said it at the screening of the New York Film Festival. I kind of went, “Oh f***.” Indeed, within about 24 hours, it kind of smacked me in the face that it was done and that this relationship that I was keeping alive was now going to be, at the very least, vastly reduced.

Follow us on Instagram, Facebook, and Pinterest for nonstop inspiration delivered fresh to your feed, every day.