Everyone Has a Tom Pritchard Story. Only I Have His Bike.

Let’s open this story with my bike, because this is a cycling magazine and because it might be helpful to begin with something tactile. To call it a bike seems so informal. It’s like calling a ’67 Pontiac GTO a car, or Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers a band. This is a bike, yes, in that it has two wheels and can get you from here to there. But it’s more than that. And I can’t tell you why just yet, but I promise I’ll get there. Meanwhile, take a look at the bike. It is finished in metallic black so subdued you have to lean in to see the sparkle; and if you do, you’ll notice a few scratches and dings on the tubing. It’s 44 years old, after all, older than me by two years. The frame is held together by Prugnat long-point lugs. Run your fingers over the hand-brazed butted tubing, the sloping fork crown, the 16.5-inch chainstay. Caress the Avocet Touring I saddle, the Satri-Gallet seatpost, the Cinelli handlebar, and the Campagnolo Record calipers

What you won’t find anywhere is a serial number or a badge or a sticker, or anything flashy suggesting a brand. From what I’ve learned about the builder, that is as it should be. If 330 million Americans walked past this bicycle, maybe 10,000 would take a closer look. Maybe a thousand would try to steal it. And I’ll bet fewer than a hundred would be able to determine its provenance. That’s all guesswork, of course, but go with me: Just .00003 percent of all Americans could recognize the value of this piece of craftsmanship.

GET THE BEST OF BICYCLING DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX EACH DAY! 📧

I love riding this bicycle. It rides hungry, sturdy, and smooth as a cat, and if you close your eyes it feels like you’re skimming the edge of a dream. If my apartment caught fire, I would make every attempt to salvage it.

I’ve called it mine, but that’s not exactly accurate. I didn’t buy it. Maybe it belongs to the universe. I feel like it found me. And that’s this story. The bike came to me by death, but this is a story about a life, one life, really lived.

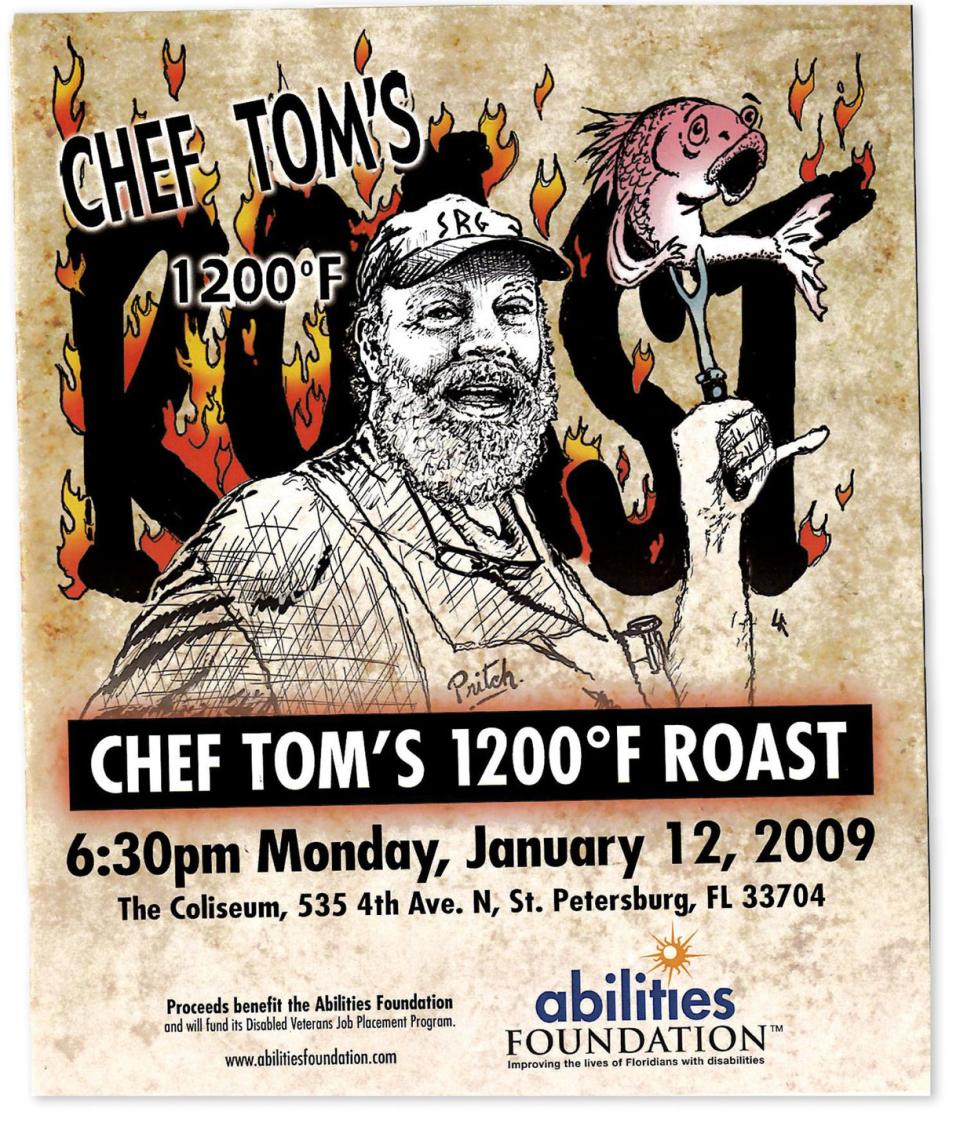

In late 2008, I got an assignment. I was working as a features reporter for the St. Petersburg Times in Florida, and my editor asked me to profile a local chef who was the subject of an upcoming charity roast, a fundraiser for disabled veterans. The guy’s name was Tom Pritchard, but everybody called him Chef Tom.

Earlier that year I’d broken a story on a different chef, a fabulist named Robert Irvine, who had a Food Network show called Dinner: Impossible and a new cookbook from HarperCollins. He had plans to open a restaurant in St. Petersburg until I reported that his impressive-looking résumé was cooked up: He had not been knighted by the Queen of England, nor did he have a Bachelor of Science degree from the University of Leeds, nor was he friends with Prince Charles. Irvine lost his TV show and canceled his restaurant plans, and I won an award from the Association of Food Journalists. I was licking my chops at the chance to fact-check another chef.

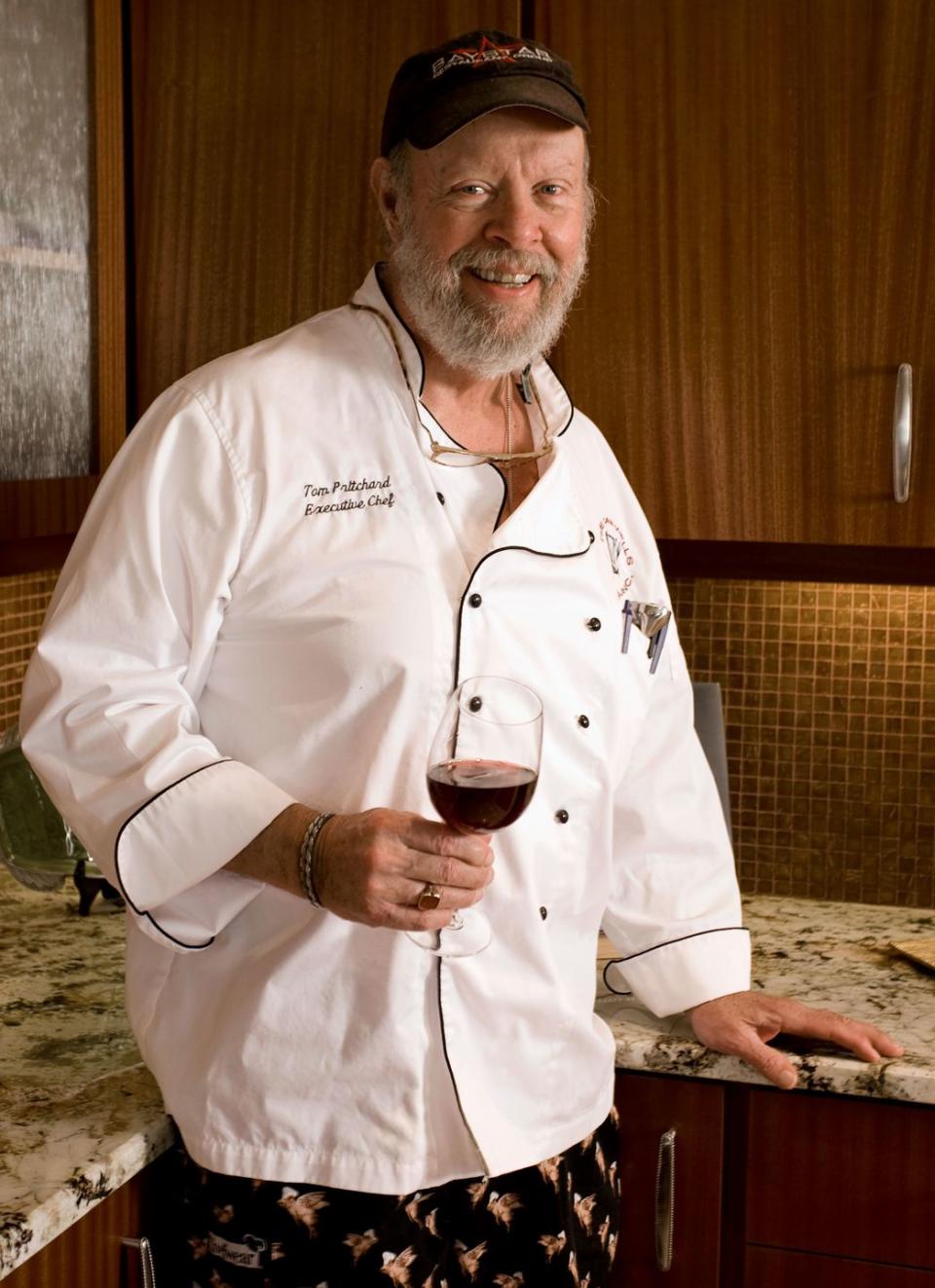

I read everything I could find about Tom Pritchard in the local newspapers, which amounted to a handful of rave reviews of restaurants he had run: the 94th Aero Squadron, the Grill at Feather Sound, and Salt Rock Grill. According to Times food critic Chris Sherman, Salt Rock Grill was the best new restaurant in the area: “...so far above beach condo bland I am tempted to invoke a word rarely heard in these parts, ‘hip,’” Sherman wrote in 1997. It took a few phone calls to get myself invited to a planning meeting for the roast. When I arrived, I found a crowd hovering around Tom. He was 67 then, and sat slouched in a patio chair, wearing shorts, sandals, and a dirty T-shirt. The breast pocket contained an assortment of ink pens, a small notebook, and a meat thermometer. The people around him were urging him to tell a story, like kindergarteners.

Tom’s bushy white-and-au jus beard couldn’t hide his grin, but he seemed uncomfortable with the attention.

Tell the one about snorting Tabasco sauce, someone said.

Tom looked up. “Anyone can drink Tabasco,” he mumbled.

Thus began the Tabasco story. He’d found himself in Aspen, Colorado, in a hard-boiled-egg-eating contest against the 400-pound hard-boiled-egg-eating champion of the world. To win he would have to cheat, and he needed something that would strip the lining of his mouth and make him salivate. So he stuck a straw through a cheese puff into a bottle of Tabasco sauce and snorted.

“I got so far ahead of him,” Tom said, “but by the end, he almost caught me because I ran out of hot sauce.”

The crowd around Tom slurped it up.

He had so many stories. He’d tried to smuggle hash into Spain in a size 13 cowboy boot box, got spooked, and dumped it. After serving in Vietnam, he’d worked as a mercenary on top-secret missions to undisclosed locations. At the Jamaica Inn on Key Biscayne, he personally thanked Richard Nixon for working out a trade deal with Mexico that allowed the free flow of tequila across the border. He once served heavyweight legend Sonny Liston seven pounds of carp.

“Every story he’s told me is beyond convincing,” a financial advisor named Howard Sachs told me back then. “He’s as close to Forrest Gump as anybody I’ve ever met.”

One of Sachs’s favorite things about Tom, he said, was that he was humble, always underdressed in his wrinkled T-shirt and shorts. “If the occasion calls for a name tag, it never says Tom Pritchard. It always says Gorilla Monsoon or Tom the Busboy,” he said.

I spent the next few days getting to know Tom, thinking the whole time that I was going to catch him lying. He met me one day outside his waterfront home in St. Petersburg. In the driveway sat his 1981 Jeep, with a stone crab claw cracker mounted on the back and a chrome pitchfork poking out the top. “That’s not a pitchfork, it’s a dung fork,” Tom said. “One thing about chefs: We’re all full of shit.”

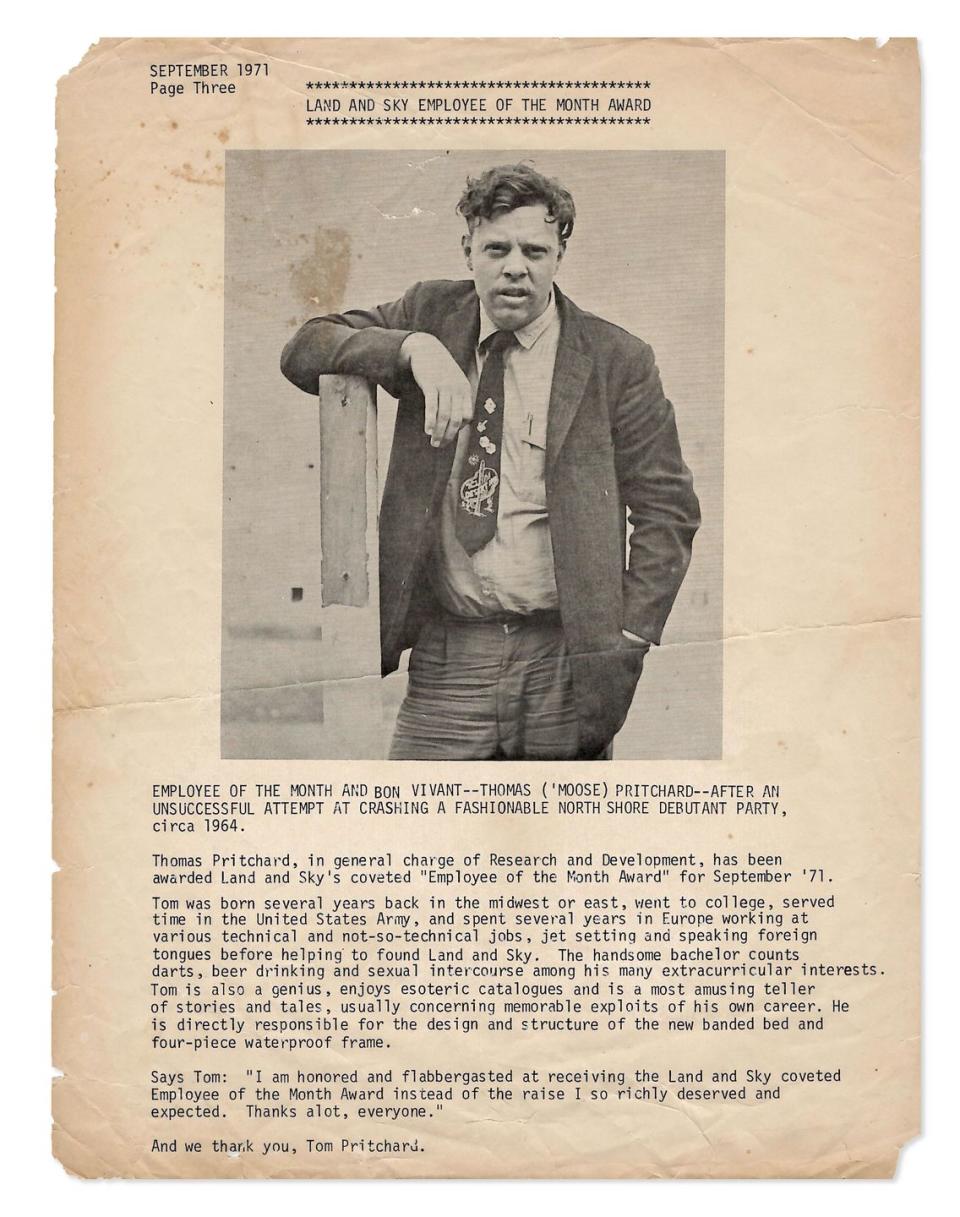

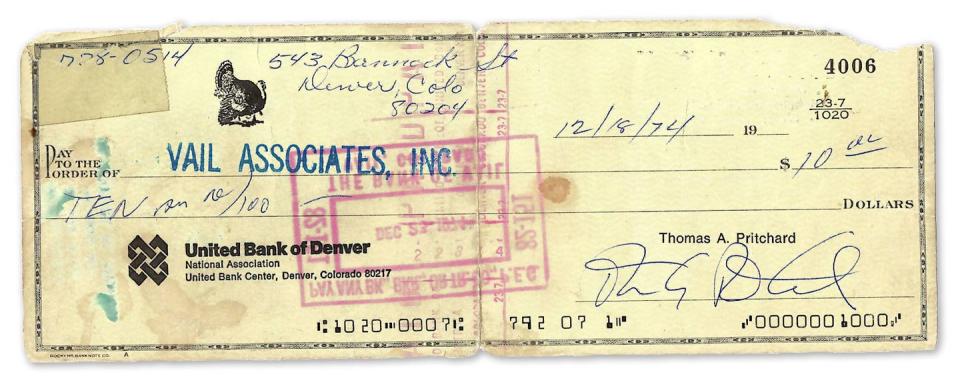

He told me his first job was shucking oysters for the bandleader Guy Lombardo at the East Point House on Long Island in the mid-1950s. He left for college, got drafted into the Army in ’64, and then traveled the world before settling on the Spanish island of Mallorca. He fell in love with an American heiress whose millionaire father had sent her overseas on account of her affinity for Johnnie Walker. After a few mysterious years abroad, Tom moved back to the States and went in with a partner on a company in Denver called Land and Sky Waterbeds. This was the early 1970s, before waterbeds were big, and the company scored an order from Playboy’s Hugh Hefner for 3,000 of them.

“I walked into the United Bank of Denver and got a huge loan with Hugh Hefner’s letter,” Tom told me. He wouldn’t say what happened to the money, but the deal went bust and he stole the loan application and fled to Mexico, where he lived for a while under the alias Moose Mazaraka.

When the coast was clear, he got a job as a cook at the Rusty Pelican in Miami with a fake résumé and no culinary training. But he was learning, always, fake it until you make it. He entered cooking contests under pseudonyms (typically, Milo Wellington—“Milo sounds sophisticated, Wellington sounds like something you eat,” he said) and hung at the elbow of famed British wine writer Clive Coates at a wine seminar. He told me that the secret to learning is hanging around people who are smarter than you.

Soon Tom was hired as executive chef for Specialty Restaurants Corp., which owned a portfolio of restaurants across the country. In 1991, he settled in Tampa Bay and launched his own place, then partnered with a seafood distributor to open his flagship Salt Rock Grill and four other high-end restaurants.

The beauty of listening to Tom was that he seemed guileless and void of pretension. Someone once wrote of Charles Bukowski that “he combined the confessional poet’s promise of intimacy with the larger-than-life aplomb of a pulp fiction hero.” That sounded like Tom. He spoke slowly and he mumbled, like he had a mouthful of marbles. You had to lean in. He was never the hero of his own stories. He often stumbled his way into some kind of fascinating situation. But there were just so many stories.

I tried to poke holes in them—to do my job—but they seemed to hold up. Richard Nixon did spend a lot of time at the Jamaica Inn on Key Biscayne.

“You hear these stories and you think they can’t possibly be true,” Tom’s longtime partner, Jody, told me in 2008, “but then years later I’ll run into somebody and find out that they’re true.”

Brad Dixon, who worked for Tom for years before becoming sommelier of one of the world’s largest wine cellars at Bern’s Steak House, told me what he calls the Confirmation Story. Brad was pouring wine for a customer named Harvey one night when Tom walked in. Harvey looked like he’d seen a ghost.

“He says, ‘Who is that?’” Brad told me. “I say, ‘That’s Chef Tom, he’s a partner here.’ He says, ‘Tom Mazaraka? Moose?’ I’m thinking, ‘Wait a second. What if Moose stole this guy’s money? Or what if Moose slept with his wife?’ Those Moose Mazaraka stories were crazy. So I go over to Tom and tell him this guy is asking about Moose Mazaraka. Tom says, ‘Oh, shit! That’s Harvey. He was vice president of the waterbed company!’”

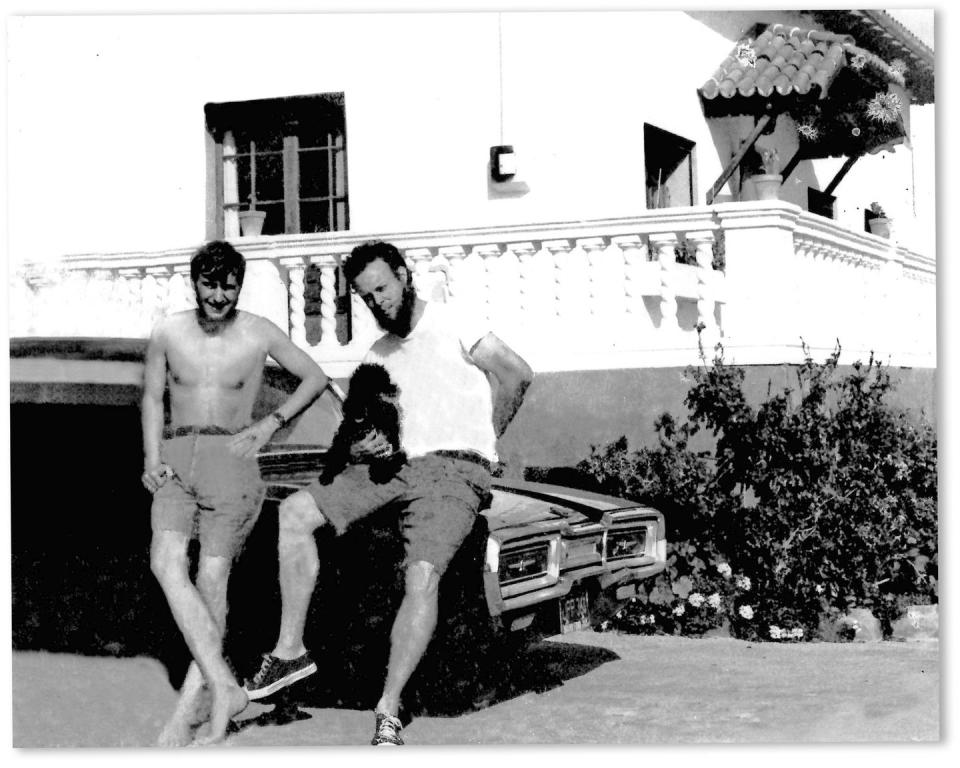

I asked Tom for more proof. He fetched a black-and-white photograph of himself in front of a villa in Mallorca, leaning on a Ford Thunderbird. He pointed to a shirtless man beside him. “He can verify everything,” Tom said.

The guy in the photo was Mike Boren. I tracked Boren down in Terlingua, Texas, on the Mexican border.

“I don’t know why the fuck he had you call me,” Boren said, “because I know where all the bodies are buried.”

Boren confirmed the bit about the American heiress and her $5,000-a-week allowance, the part about being mercenaries, about smuggling hash in the cowboy boot box. He told me Tom once cooked Thanksgiving dinner for 300 people in Mallorca on a whim. “Everybody thinks [Tom] is full of shit,” Boren told me. “He’s not full of shit at all. He’s just bigger than life.”

Most stunning about the man’s life was the sheer number of people he had helped in the cutthroat food industry. It seemed like everybody running a kitchen in Florida had either worked for Tom Pritchard or somehow benefited from his support. He was Thomas Wolfe’s “huge hinge of the world, and a grain of dust; the stone that starts an avalanche, the pebble whose concentric circles widen across the seas.”

My story ran in January 2009, headlined Moose and the Myth. That’s when things got weird.

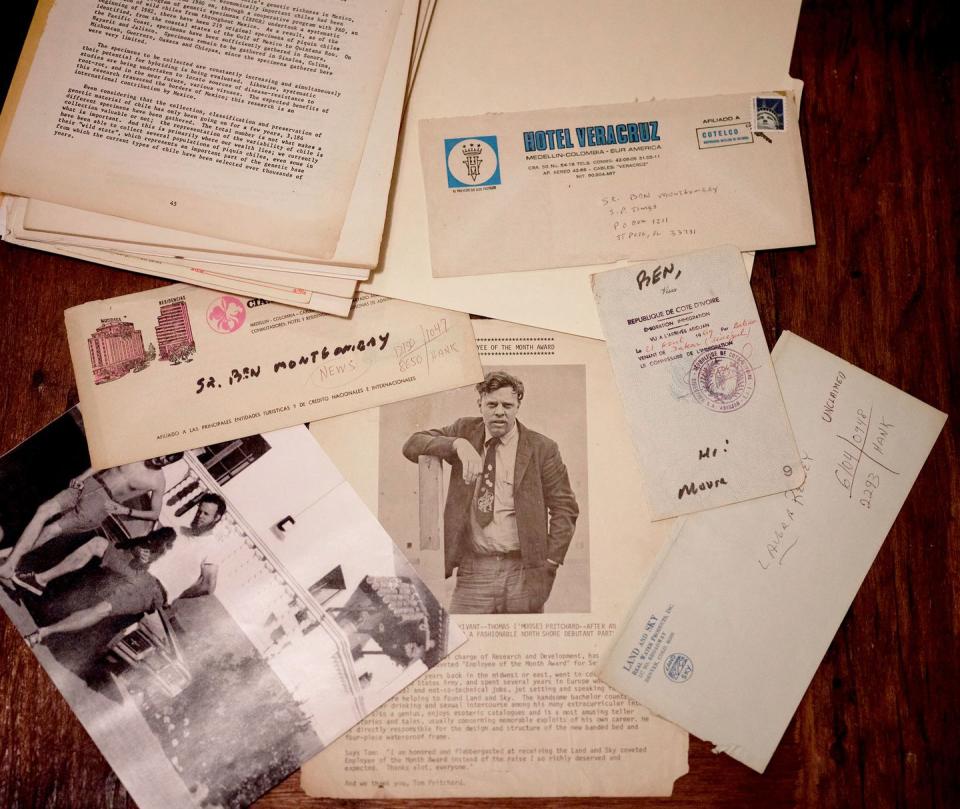

The first note arrived a few months after my story ran, in a weathered envelope from Hotel Veracruz in Medellín, Colombia. Inside was a page ripped from a passport book, with a stamp from République de Côte d’Ivoire marked 1969. In black Sharpie, it said:

BEN,

Hi!

Moose

Then came another, a few months later, in an envelope from “LAND and SKY Real Water Products, Inc.” on South Broadway in Denver. Inside was a canceled check for $10 dated December 1974, signed by Thomas A. Pritchard. On the back he had written:

BEN --

Aha

TP

And so it went. Every few months for the next five years, Tom would drop me bits of mysterious ephemera, each one a piece of the puzzle of his incredible life, some corner of confirmation that the stories he told were true. He sent me a page from a Land and Sky company newsletter, which designated him employee of the month in September ’71: “The handsome bachelor counts darts, beer drinking and sexual intercourse among his many extracurricular interests,” it read. “Tom is also a genius, enjoys esoteric catalogues and is a most amusing teller of stories and tales, usually concerning memorable exploits of his own career.” (Genius? “Tom’s a genius,” Mike Boren told me. “A real, honest-to-god, super-IQ genius.”)

Why had he waited? The story I wrote left open the possibility that he was full of shit, but here was proof—in dribs and drabs—that he was telling the truth, that he was some nonfiction version of Forrest Gump.

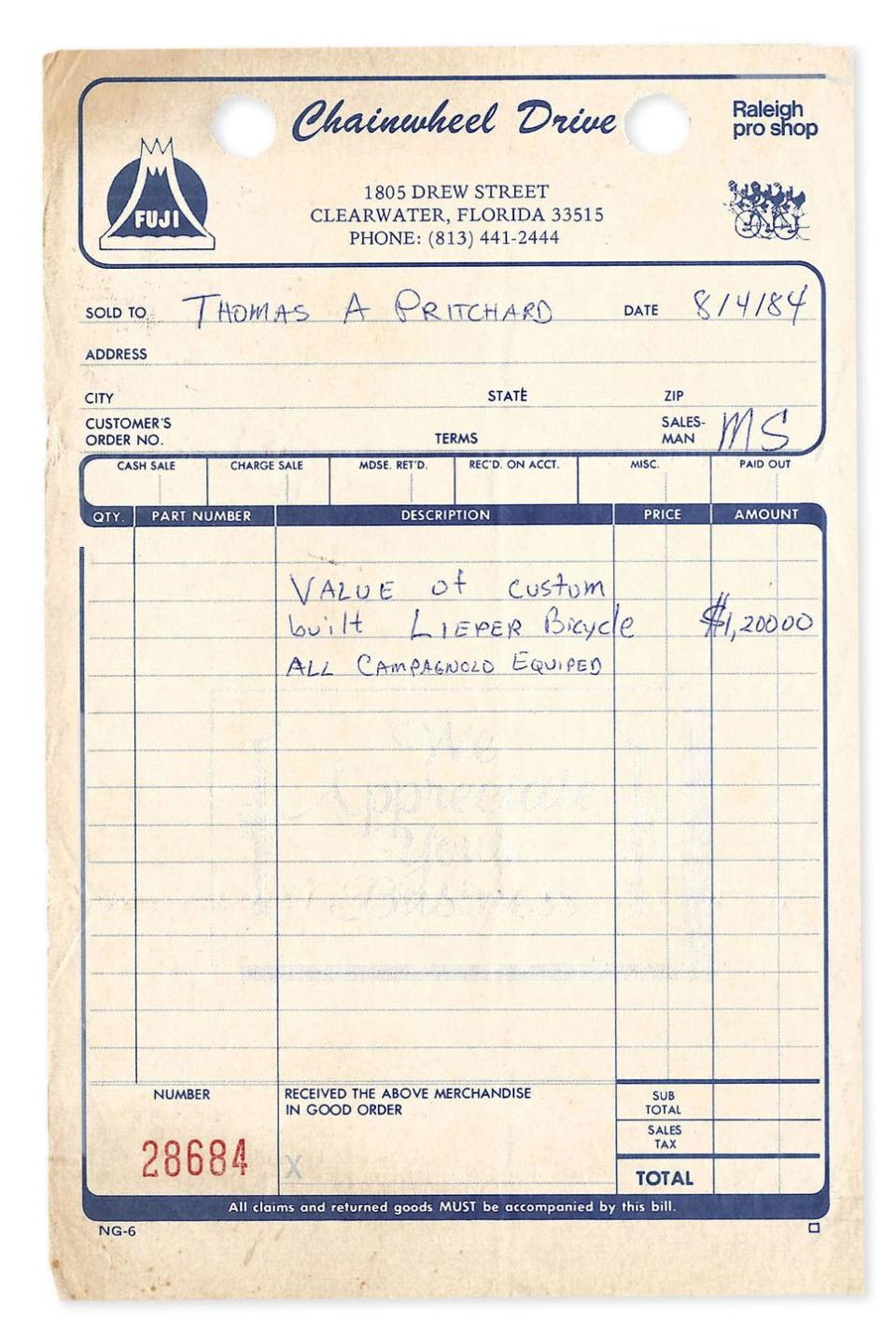

It was around 2012 when he first mentioned the bike. I’d been riding more, and he said he’d bought a bike in Denver in the mid-’70s. Like every Tom story, this one was special. He said he was trying to get the attention of a beautiful young woman who was a serious cyclist, and he couldn’t just ride up on a Schwinn Varsity. So he went to a shop expecting to spend a little money, but wound up dropping some serious dough on a very nice bike. And it worked! He got the girl.

A few weeks later, another piece of ephemera showed up in my mailbox, a note on a sepia bike shop receipt. He’d evidently had his bicycle appraised in 1984, and the appraiser valued it at $1,200—close to $3,000 in today’s economy.

He’d eventually lost the girl, but he still had the bike after all these years.

Over the last years of his life, Tom and I became good friends. My story about him had been anthologized in a book of food writing called Cornbread Nation, and Tom got a real kick out of that. Once, he took a limo from St. Pete to Tampa to take me out to Bern’s Steakhouse, where we drank wine from our birth years. He showed up randomly at one of my book talks in 2014 and bought five copies for me to sign. I called Tom when some big-shot writer friends came to town—guys like Chris Jones from Esquire, and Parks & Rec co-creator Michael Schur—and he invited us to Salt Rock and treated us like kings. He gave my buddy Wright Thompson a free pour of his Screaming Eagle, a cab that costs as much as a car.

The closer I got to Tom, the more stories I heard. Bjorn Brunvand, Tom’s friend and lawyer, told me about meeting Tom for dinner in 2008 at a fish shack on the beach. When Bjorn arrived, Tom was sitting at the bar beside an old man, and he introduced the two. Bjorn, who is from Norway, didn’t recognize the man’s name, but told his wife after dinner that he’d eaten with Tom Pritchard and John Prine. John Prine! she exclaimed. “I had no idea who he was,” Bjorn told me.

By early 2015, Parkinson’s was wrecking Tom. One hand shook terribly. He needed a walker to get around. The last time I spoke to him by phone he told me he was working on a cookie recipe. White chocolate, macadamia nuts, Dr. Pepper.

I soon learned that he had elected to have some kind of experimental surgery to reverse the effects of Parkinson’s, and things hadn’t gone well. I saw him in the hospital in October 2015. His face was swollen and blood pooled around his eyes, like he’d lost a bar fight. He recognized me but could only mumble. A nurse wiped his mouth.

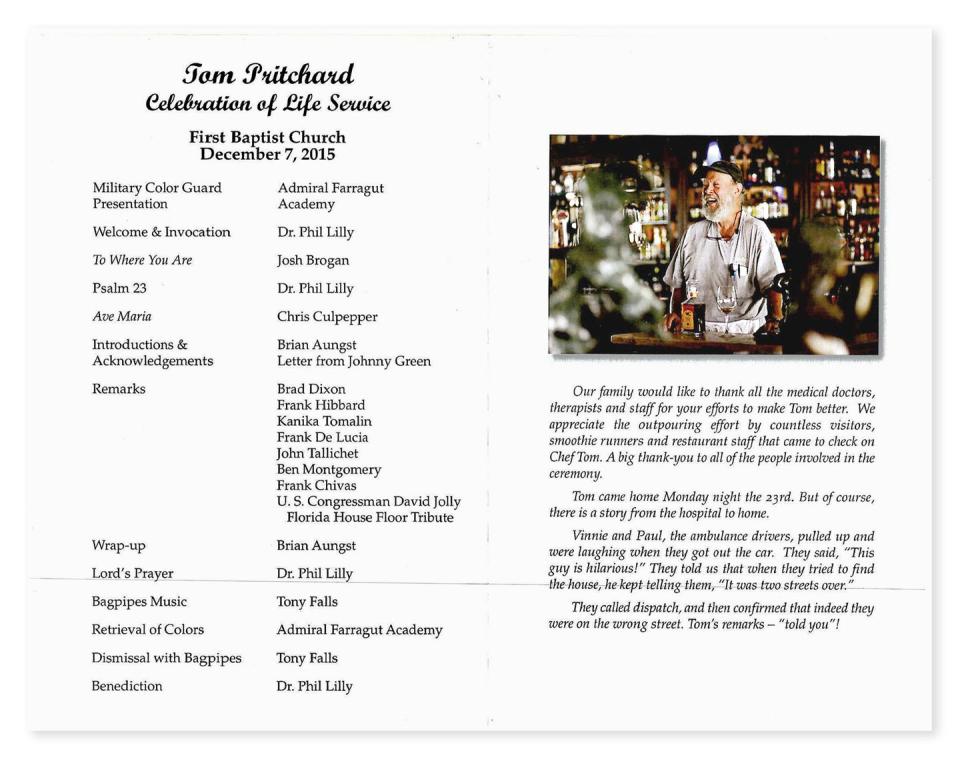

He died the day before Thanksgiving that year, at age 74. Congressman David Jolly read a tribute on the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives, calling Tom “larger than life.”

His funeral, attended by hundreds, was sad and hilarious. I took notes but kept just one page. I can’t remember who said it, but this is what I wrote: “Every man’s life ends the same way. It is only the details of how he lived that distinguish one man from another.”

The funeral was also more proof that Tom was telling the truth. Mike Boren showed up from Texas. Harvey from the waterbed company was there too. Cooks who’d been helped by Tom in ways big and small told stories about his kindness and chicanery. It wasn’t the scene at the end of the movie Big Fish, but it was close.

It occurred to me that my disbelief never bothered Tom. He knew his stories would outlive him, and that I’d learn the truth.

I sought out Jody, his old partner, and asked about his storied bicycle. I told her I’d buy it if she planned to throw it away or sell it at a garage sale. She promised to call.

Another year ticked by before Jody reached out. She’d finally cleaned out Tom’s storage unit and found the bicycle. It was mine if I wanted it, she said. I drove over.

The bike was a cobweb-covered mess. Rotten tires, rusted spokes, broken chain. I thought maybe I’d hang it on my wall as an art piece, to remember Tom. I knew it meant something to him, but I could barely recall the specifics of this one story.

Back home I dug through my Tom Pritchard stuff, through all the letters and passport pages he had sent me over the years. I found the appraisal scratched on a sales receipt from Chainwheel Drive in Clearwater, Florida. “Value of custom-built Lieper bicycle, all Campagnolo equipped: $1,200.”

Some quick googling schooled me on the level of respect cyclists have for old Campagnolo parts. But what kind of bike was it? I asked around about Lieper bicycles. I scoured the Internet, digital newspaper archives and impassioned bike forums. I turned up nothing at all about Lieper (or any similar spelling) bicycles. Maybe Tom or the appraiser was just confused. Maybe that referred to something else altogether. I studied the frame but couldn’t find a serial number or marking of any kind. I noticed lettering beneath the paint on the dropouts, but it said Campagnolo too. The only possible identifier I could find was a metal bike license plate fixed to the saddle with a twist of wire.

5826 D.B.T. 1976

I phoned the Denver police, but they didn’t have records that far back. I took the bike to a friend who owns a shop called Vélo Champ in Tampa and told him the story. “You’ve definitely got something special here,” he said. He posted photos on Instagram to see if anyone recognized the craftsmanship.

I called Tom’s old friend Mike Boren to ask him if he remembered the bike. He’s 77 and still lives in West Texas.

“I don’t remember the girlfriend part,” he told me. “I just remember Tom being really proud of getting this bicycle that was out of this world.”

I started cleaning it up, polishing parts. On a whim, I googled “oldest bicycle shop in Denver,” and turned up Turin Bicycles. On the map it was a mile from the old Land and Sky headquarters. Who knows? I’ve made crazier phone calls.

The man who answered sounded like he had a few years on him. He was Alan Fine, and he’d opened the shop in 1971. I said I was trying to figure out the history of an old bicycle left behind by my dear friend. I started to tell Tom’s story about buying the bike and using it to win the love of a beautiful woman.

“How do you know it came out of Denver?” Fine asked.

“The guy it belonged to told me,” I said.

“What guy did it belong to?” he asked.

I almost said Moose Mazaraka.

“Tom Pritchard.”

He didn’t miss a beat.

“I know Tom,” he said.

Of course he did. Forty-one years had passed, but nobody forgets Tom Pritchard. What is four decades but a blink for a transcendent story? We remember Gilgamesh, and Odysseus, and Jesus Christ.

“And I know the girl he was after,” Alan Fine told me. “She was my girlfriend.”

I laughed and almost cried, and noticed that my arms were covered in goosebumps. He was telling stories from the grave now. I could see Tom, younger, his hair a mess, walking into Turin Bicycles so full of audacity, knowing he was about to buy a bike from a man in order to get the same man’s girl.

I emailed Fine a link to Tom’s obituary and some photos of the frame, just to be sure.

“The bike is definitely an Eisentraut ‘Limited’ produced exclusively for the Turin Bicycle Co-op,” Fine wrote after looking at the photos I sent, “and sold to Tom at our store here in Denver.”

(By the time I tried to get more detail on what Fine thought about Tom chasing his girl, he had sold the shop in Denver after nearly five decades in business and retired. I couldn’t track him down. It was one more loose end in the enigmatic life of Tom Pritchard.)

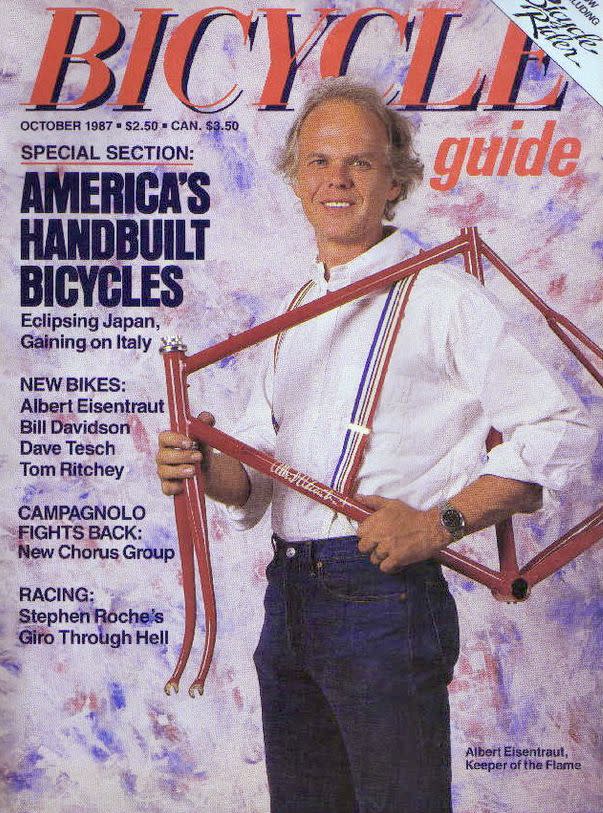

Bicycle Guide put Albert Eisentraut on its cover in 1987 and called him the “keeper of the flame.” The cycling writer Owen Mulholland wrote that Eisentraut had built more than 2,500 frames since the late 1950s and had taught a generation of American framebuilders their trade. “To the temple… came everybody who was anybody and [many] returned home with an Albert Eisentraut jewel in hand,” he wrote. “John Howard, Mike Neel, Flip Waldteufel, Lindsay Crawford—these were some of the more prestigious names mounted on ‘Trauts’ in that era.”

Eisentraut trained Bruce Gordon, Joe Breeze, Skip Hujsak, and Mark Nobilette, among others. But even if Eisentraut was the “midwife-become-godfather to the renaissance in American framebuilding,” as Mulholland wrote, he would never be widely known.

In his review of Eisentraut’s “Limited” road bike in this magazine in April 1976, writer Wallace Clements noted that the “excellent” bike was “sparsely adorned with nameplates and decals: no nameplate at all in the usual place on the front of the head tube.” He went on: “This was one of the least labeled bicycles I have seen—a refreshing change.”

That was Eisentraut’s way, and why Tom’s bike was an enigma for so long.

“Bicycles are not built to be used as status symbols,” Eisentraut himself wrote in a chapter on framebuilding for a book called Bike Tripping, published in 1972. “The cyclist should ride his chosen bike, instead of bullshitting about its angles or its chain stay length.”

Tom would approve. Even when he was well known, cooking for charity functions, his nametag always said something like “Tom the Busboy.”

That’s what I like most about his bike. And when I ride it around Tampa, I think of him. I can see big Tom in Denver, pumping hard, trying to catch up to a woman and hoping she notices his bicycle that is unadorned yet amazing, without pomp but of supreme quality, understated but for the story it tells, a perfect match for the man in the saddle.

You Might Also Like