Espresso: Britain’s Coffee Revolution

This article originally appeared on Peloton Mag

Coffee and cycling are so symbiotically connected that it is tempting to think that the two cultures must have developed in unison. Of course, coffee has been around for thousands of years and bicycles are very much the junior partner. In Great Britain, the now-widespread coffee culture, with all its intricacies and trends, has only been around for the last quarter of a century. The arrival of corporate behemoth Starbucks on London's Kings Road in 1998 was arguably the biggest factor in Britons becoming used to decent coffee. Before that the British mainly drank freeze-dried instant coffee from jars or, if they were trying to be posh, plucked up the courage to tackle a cafetiere.

British cyclists are only very recent converts to coffee. Across the country, amateur cycling clubs have traditionally been based around the Sunday club run, an out-and-back ride into the countryside. When I was growing into my trade-team cycling jerseys in the late 1980s, the weekly club run was a fixture in my weekly routine, something to be relished, and sometimes feared. Only the nastiest weather could put off my father and me from turning up. Invariably, the target (and, if you were suffering, a very sweet relief) was a village cafe where tremendous quantities of tea and cake would be consumed. So far, so quintessentially British. This was when cycling was a niche activity. Now cycling is as popular as golf and there are thousands more cyclists on the lanes every Sunday morning. The bucolic sound of birdsong is accompanied by the buzz of freehubs. In the cafes, now, cyclists sip skinny lattes and crunch on biscotti. So how did Italian coffee take over our lives?

The central London district of Soho is not big, less than one square mile. Yet it is so densely packed with history that with every step its visitors sense some very famous ghosts. While Soho--along with neighboring Fitzrovia--was home to the cozy pubs in which great writers of the 1930s and '40s got quietly sloshed, it was during the '50s that the area really came to life. After World War II, London was a gray, damaged place, badly in need of an injection of energy. A maze of narrow streets and courtyards, Soho is bordered to the north by Oxford Street, to the south by Shaftesbury Avenue and to the east and west by Charing Cross Road and Regent Street respectively. The area had long attracted bohemians. Percy Bysshe Shelley and William Blake both lived on Poland Street. On these streets aspiring musicians mingled with poets, journalists and artists. The notoriously drunk columnist Jeffrey Barnard could be found propping up the bar in the Coach & Horses alongside artist Francis Bacon. In the 1950s, that spirit was about to be reignited. The birth of rock 'n' roll would put Soho at the center of a teenage revolution.

Early in the decade there was an explosion in the number of music venues putting on skiffle, jazz and folk nights. Instrument shops and recording studios followed. On Wardour Street, the Marquee Club opened in 1958 and soon became the flagship venue for new rock bands to play. During the following decade it played host to The Rolling Stones, The Who, Jimi Hendrix and many more. The Beatles recorded The White Album in 1968 at Trident Studios in St. Anne's Court. Over the following years the many recording studios around Denmark Street attracted artists like the Sex Pistols, Queen and David Bowie. For jazz fans, there was Ronnie Scott's basement club on Frith Street, and the proliferation of folk clubs drew musicians such as Bob Dylan and Peggy Seeger. Music was very much the driving force behind the regeneration of Soho.

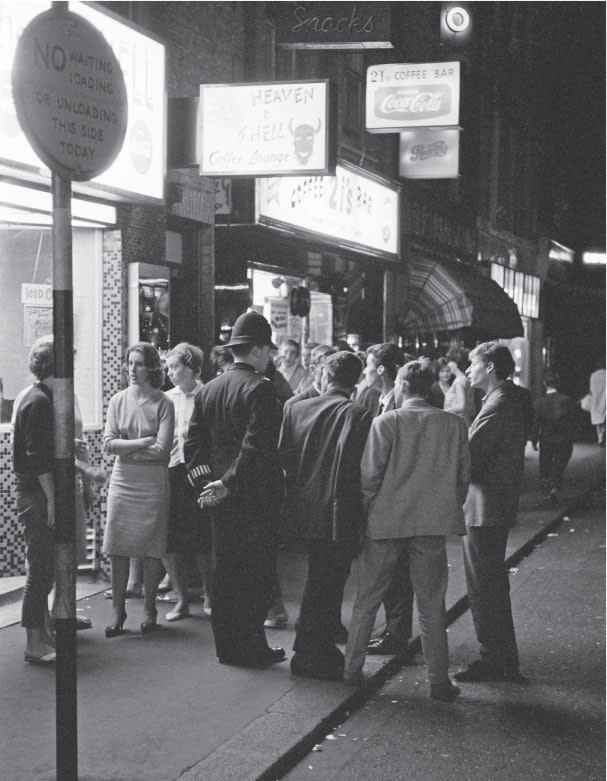

And all the teenagers drawn to this happening area needed somewhere to hang out, to talk and flirt and put off the journey home to the suburbs. To cater for them, a new type of cafe began springing up: the coffee bar. Before the early 1950s cafes in London served tea, cake and hearty, heart-attack-inducing fare such as fried breakfasts, sausage, fries and sandwiches. Ranging from the genteel to the downright scruffy, the only distinctions in their respective clientele was along class lines. And they were all polite, stuffy places. In the 1950s the new coffee bars of Soho aimed for young customers, irrespective of class. They played rock music and opened late to catch the post-gig trade.

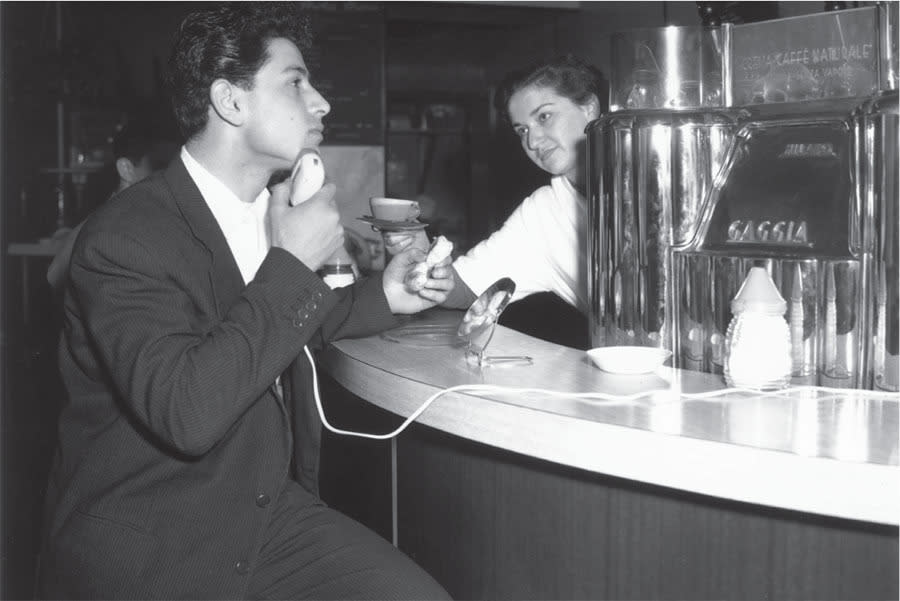

In 1953, the Italian actress Gina Lollobrigida officially opened London's most influential Italian coffee bar. The centerpiece of the Moka Coffee Bar on Frith Street was a new Gaggia coffee machine. And London was not so far behind Italy in this respect. Although Achille Gaggia filed for a patent for his espresso machine in 1938, it would take a further 10 years for La Classica to go into production. From 1948, coffee bars across Milan were getting to grips with all those newfangled (but very effective) levers and buttons, and the revolution was about to head north.

The unlikely hero of our story is an Italian dental equipment salesman named Pino Riservato. As he traveled through England for his work in 1951, Riservato was appalled by the coffee (often made from chicory) being served in cafes. Through a family connection he was able to start importing Gaggia machines to London, but he failed in his early attempts to persuade cafe owners to invest in what must have been a rather intimidating machine. Undeterred, Riservato decided to set up his own coffee bar, the Moka. He found a bombdamaged launderette on Frith Street and fitted it with a Formica bar, bright lights and metal stools. The Moka quickly became popular, serving over a thousand cups of coffee a day. Riservato's plan worked. Soon, coffee bars were popping up across Soho, all with a spluttering, steaming, shining Gaggia.

A template soon evolved; there was a long wooden bar, behind which sat a huge gleaming Gaggia coffee machine. In the public space, the owners squeezed in as many plastic or wooden tables as they could, though they often left a space for dancing, or a small stage for bands to perform. A jukebox loaded with the latest hits was an essential feature. As the number of coffee bars in Soho grew, their owners went for bright exterior designs and outlandish themes, aimed at attracting customers in what was becoming a very competitive market. In the 1950s and '60s London architects rarely lowered themselves to working on shops and coffee bars, so the designers of coffee bars had an amateurish enthusiasm that largely ignored the prevailing Modernist aesthetic.

Le Macabre on Meard Street was a good example. Here, the hip young crowd could drink cappuccinos while sitting in a coffin, surrounded by cobwebs and skull ashtrays. On the walls were paintings of naked girls being pursued by skeletons. Long before Goth and Emo, London's morbid teens could hang out here and pretend to understand existentialism.

Today, there are few traces left of Soho's coffee bar explosion. By the mid-1960s the hip coffee bars seemed outdated and many went out of business. Soho remained the center of London's counterculture throughout the '70s and '80s but soaring rents and an influx of corporations--including advertising agencies attracted by the creative atmosphere--blunted the edge of the place. But the legacy of Signor Riservato and his colleagues lives on. Throughout London, throughout the whole country, it is now possible to get a really good espresso. So much so that we take it for granted. As legacies go, that's a pretty good one.

For exclusive access to all of our fitness, gear, adventure, and travel stories, plus discounts on trips, events, and gear, sign up for Outside+ today.