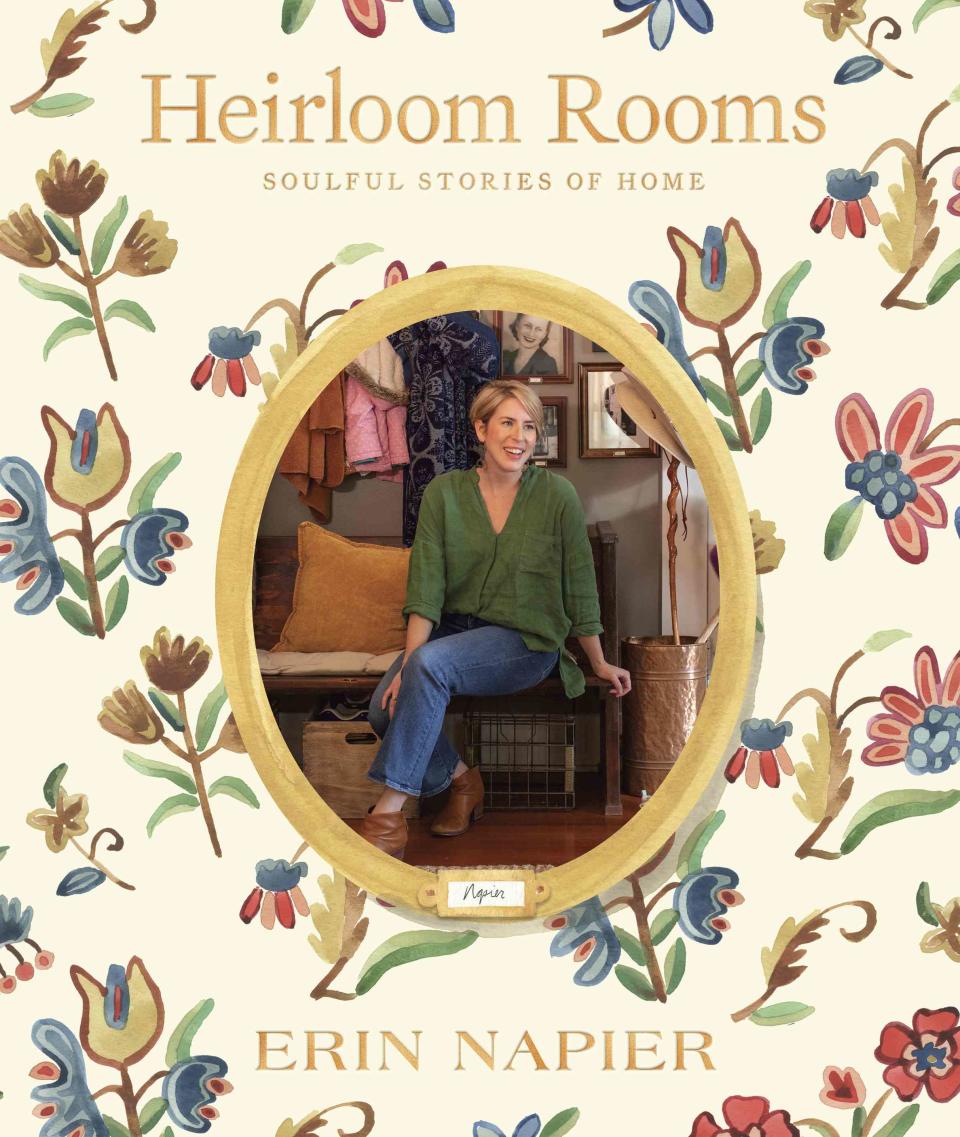

Erin Napier's New Book Was Inspired By This Home Full Of Memories

An exclusive excerpt from her new book.

Erin Napier

The home in Laurel, Mississippi, where my family lived when I was born was built by my grandfather James Rasberry in 1955. This is what I can remember about it: The beige marbled shag carpet in the den, where I have seen video of me in a Playskool car, babbling to my mama; this is where I lay on the floor watching Pippi Longstocking on VHS over and over. The almond and brown seashell-themed guest bath in the hallway, across from my bedroom. The sunken carport turned rec room off my brother’s bedroom, where Clark played Ping-Pong with his friends, and I whined because they wouldn’t let me play because I was nine years younger. I remember the light-blue chenille bedspread that covered me on my parents’ bed, where I slept every night of my very young childhood. I remember the rattan barstools and the burnt-orange Formica countertops and the rust-colored medallions patterning the vinyl floors of the kitchen, where Mama prepared my Eggo waffle each morning, where she made the best strawberry milkshake I’ve ever had (she used a couple spoonfuls of strawberry jam, and it was what love tasted like). Christmas occurred in only one room in my memory: the formal living and dining area at the front of the house. The tree sat, lit with the rainbow of C9 color, in the bay window. There were bamboo sofas with silky floral cushions in shades of green and blue, with piping around the edges. Like outdoor furniture, but used indoors, they had the look of beachy eighties elegance. The brass peacock guarded the fireplace box, sooty from the rare and few fires Mississippi weather allowed. The formal dining table, where I once played with a brand-new electric typewriter, sat under the glow of the wood and glass china cabinet.

Erin Napier

Erin Napier

I cannot remember what was inside the china cabinet. I cannot remember if the floors were oak or pine in that room. I cannot remember the color of the hallway that kept us safe during the Glade tornado. Was it wallpapered? Was there paneling? I cannot remember exactly where my armoire sat in my bedroom, or if there was a closet inside my parents’ bathroom. These things I cannot remember don’t matter, not really, except that forgetting them feels like I am forgetting the eye color of someone whom I loved very much. I remember being loved and finding the first seedlings of my imagination and creativity in that house. I pass that house all the time, where baby swings now hang on the front porch. I wonder if there is still carpet in the den that those babies crawl on.

In 1992, when a local dentist made an offer on the old brick ranch, my parents built a new house next door, and we moved. It was southern traditional and very much in vogue for the 1990s in Mississippi. I slept there for the first time as a seven-year-old, and I am there two or three times a week still. I don’t have to remember everything about this house because it is not in the past yet, but I find myself taking photographs of things I will miss someday. It might not always be ours, so I must own what I can from it: making a tiger costume with my mom at the breakfast table from a foam mattress topper, paint, and electrical tape; learning from my parents how to strain a mountain of berries to make one perfect pink jar of mayhaw jelly over the ceramic-top stove; the memory of Mama dropping a pickle jar on the Saltillo tile floor the week we moved in. The crash as it tumbled from the countertop sounded like the end of the world, a movie sound effect. She warned us to stay out of the kitchen until she had cleaned it all up to save our bare feet from a billion razor-sharp splinters of glass scattered like birdshot. We still found the glitter of it years afterward when the fridge was replaced. It comes to me now that when we remember the homes we grew up in, we are really remembering the ways we felt in them, the people who lived in them, and the ways they cared for us.

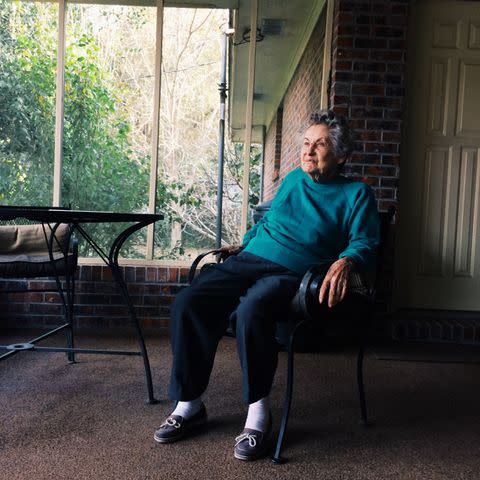

In 2015, my grandmother moved to assisted living after more than a decade of living alone since my grandfather’s passing in 2001. In 1982, after selling my parents the original 1955 ranch (the one I was later born in), my grandparents had built another brick ranch on the back of the family property, over the pond and through the woods, in a thicket of pine trees, beside the two-acre garden they planted. Their house was the place my family had gathered every Sunday and holiday since. As my grandmother’s spark and health became more fragile in 2014, I had the thought to photograph a few rooms of her house with my phone—her ordinary rooms, unchanging since my earliest memory, except for the addition of a walker. I looked at the images days later and felt haunted by them. Though she wasn’t pictured in all of the photographs, she is there in every one. These photos became the impetus for writing this book, where by walking through each room and memory in the home Ben and I made together, we keep our life there alive forever. I hope it encourages you to walk through yours—rich with milestones and love and remembrance that outlasts trends and rugs and sofas—as well.

There is grief in letting a house go. This is what I wrote in March 2015, the day I realized my grandmother’s home would soon be a new beginning for a stranger who wouldn’t know that the piano in the living room, which we played on sick days spent at her house, was out of tune; a stranger who would eventually cook and eat and sleep there and paint the rooms different colors than the ones in the background of my memories:

Erin Napier

Tonight, my heart is at her tidy little brick house just across the pond from my parents’. It’s on her back porch, in the white rocking chairs where it always smells like four-o’clocks in bloom. It’s in her bathroom with the red heat lamp that she would click on when I would spend the night as a child and take bubble baths with those flowery Avon potions. It’s in the glass pitcher of fresh sweet tea, always in her refrigerator, with a crumpled, homemade aluminum foil lid. It’s in her wallpapered and country blue dining room, and in the ring of bricks in the side yard where she would build campfires and roast marshmallows for me and my cousin Jim when we got to sleep over. It’s in the red-and-white striped flannel blanket we would use to build forts in the living room with chair backs and rubber bands. It’s in the Reader’s Digest condensed book hardbacks with the illustrated endsheets of ships and pirates that sit on the bookshelves in the living room. It’s in the secret passageway to the garage beside the fireplace, where they kept the firewood stacked for cold winter days. It’s in her utility room with the wall of canned figs and tomatoes, empty Ball jars ready for summer’s bounty. I know that those places aren’t her, that a house does not make a home, but right now it feels like it.

And months later, I wrote about moving her objects, her belongings, her life lived well, out of that house:

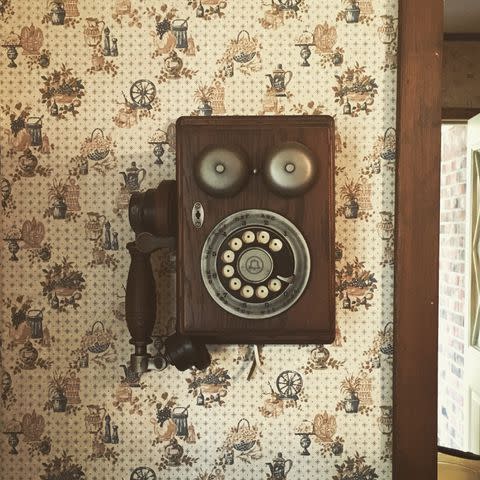

But the things I wanted pertained to my memories with Mammaw in her kitchen, where she taught me to make biscuits, her spicy rice, pie crust cookies. We would have late-night snacks when I slept over (mild cheddar cheese and Ritz crackers, with hot chocolate if that’s what I wanted), and though she was the greatest cook in the world (fried chicken! macaroni and cheese! Spaghetti and meatballs!), the only dish she never cared for enough to master was the grilled cheese sandwich (microwaved, yikes!). Those are the memories I return to the most of my time with her, and so today I brought home the things that made my heart cry out when I saw them: her Blue Willow and Currier and Ives china. The Christmas cookie jar she bought in 1997. The silverware we used at every Sunday lunch. One wooden chair, from the guest bedroom, sturdy and lovely. The red Dutch oven, the crevices and edges tarnished black from years of hot grease. The heavy cobalt blue canisters for flour, sugar, tea, and cornmeal. Inside the canisters I found her last ingredients, the old plastic scoops buried, ready for baking. The antique rotary phone on the wall by the door that I used to call my mama and say “Good night!” when they were away on overnight trips, leaving me with Mammaw and Pappaw to build campfires, chew sugarcane, put together puzzles. Thirty-one years of my life spent visiting my grandparents, and I pulled out of the driveway today with only a precious few things, an armload, that it felt like their souls are still attached to, even if a little dusty.

Erin Napier

Erin Napier

Ben and I believe so passionately in restoring old houses because it feels like we have a responsibility to keep the memory of people and places from being swept away. We recognize the humanity in a house: brokenness is not permanent, anything can be redeemed. Like people. I think that is why, back then walking through the emptied rooms of my mammaw’s house, and still at the start of every demolition on Home Town, I find the raw vacancy of a house hard to look at. In the same way it must take surgeons time to get used to the sight of the blood of their work, the sight of a ramshackle vacancy is unsettling to me. Houses are built with intention and personal preference; they are human creations that reflect human longing: living rooms and babies’ rooms, kitchens, porches—they are designed to keep us safe as we go about living and loving each other.

And so, this book is an exercise in documenting the home where Ben and I first became a family, and I invited other friends and family to do the same in their homes. We have taken staged photos of our home before, and those pictures portray a version of the truth—the most aesthetically pleasing truth. But people are not perfect, and neither are the homes that keep them. I asked these friends to photograph their rooms the way they actually live in them, unstaged, imperfect. I asked them to tell me what moments made their houses feel like family members, and I hope it will encourage you to do the same. It is not only perfection that is worth documenting, but what is personal. Your home does not look like a magazine article, and it was never meant to. It is an ever-evolving heirloom keeping step with the humans who are the custodians of it. We are passing through, but our homes live on after us; they are passed down and re-envisioned. Document the experience of your evolving home as if it were your growing baby even when it is an imperfect composition of unsorted laundry and broken toys; capture its dimples and first steps, its smells and sounds. There is so much joy in opening up the baby book, isn’t there? To compare the little black footprints to the shoes in the hall? Life is forever evolving, and our homes are proof. Look at how far we’ve come.

About Heirloom Rooms: Soulful Stories of Home

Erin Napier, designer, host of HGTV’s Home Town, and author of Make Something Good Today, returns with a gorgeously illustrated and one-of-a-kind celebration of the homes we live in and love. To buy: Heirloom Rooms: Soulful Stories of Home

Related: Erin And Ben Napier Share Their Dream Home In The Mississippi Countryside

For more Southern Living news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on Southern Living.