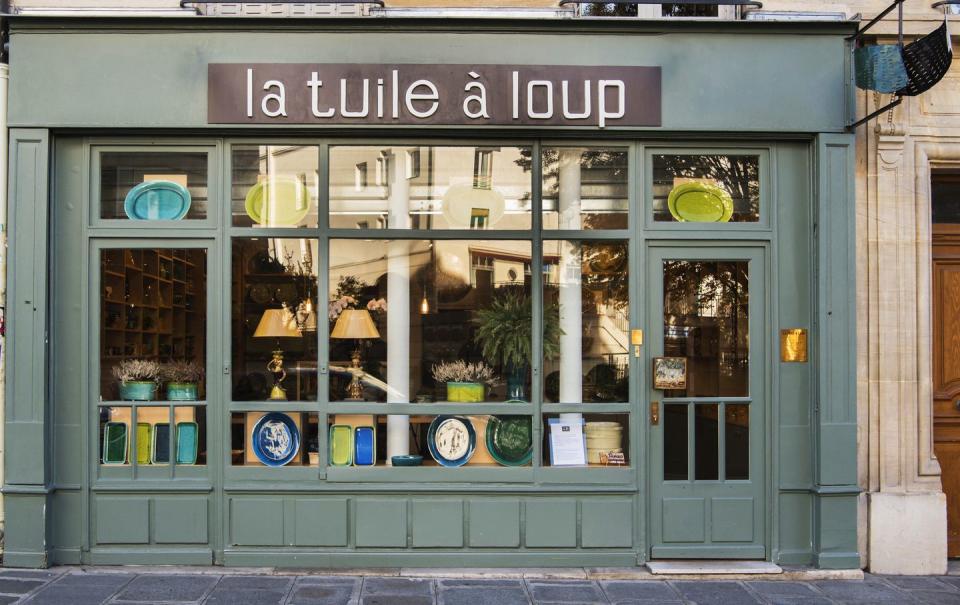

Eric Goujou Keeps the Art of French Ceramics Alive With His Boutique La Tuile à Loup

Eric Goujou watches the way we entertain. The owner of celebrated ceramics boutique La Tuile à Loup studies what appears on our tables from one year to the next, from one corner of the world to another. He can tell you, for example, that modern French hosts are bypassing big, commanding salad bowls in favor of smaller dishes “to offer more of a variety.” Today’s in-demand soup bowls, he contends, are deeper and smaller than their predecessors (more suitable for popular Asian-style soups), he says, and Americans are unwavering in their love for blue-and-white dishes of all shapes and uses.

He isn’t in pursuit of trends, but rather, permanence. “The French grew up with aptware, marbleware, and folk art pottery, and have grown to love the elements, the colors, the familiarity,” he says. “They aren’t looking for pieces that feel new. They want well-crafted pottery that fits their daily routines.”

Think of Goujou, then, as an artistic historian, resolute in ensuring French ceramics traditions retain a place in 21st-century meals, gatherings, and decoration. In his 5th arrondissement shop, he represents roughly 30 artisans, many of them baby boomers with thousands of hours honing their crafts in workshops well outside of Paris—places like Burgundy, northern Provence, Savoy. “They cannot create in a world with so much going on, information coming in from all directions,” he says. “They need to step back, build in their bubbles.”

Goujou is the bridge, setting out by train or car to the countryside to see one or two artists at a time. “Often I bring pictures of the things that I see, and I ask them to explore these ideas,” he says. “Maybe they do it, maybe they don’t.”

He is gradually merging modern life with an old and rather rustic art—without interrupting it. Technique remains untouched, as does the purity of the craft. “They are masters, and creative freedom is the most essential element,” says Goujou, admitting a fascination with “the human element of the work.” It’s what drew him to the “vocation,” as he calls it, in 2006, when he traded private banking for ownership of the shop, which has been around since the 1970s. “When you go to a kiln opening, you never know what you will get. Sometimes, the work is perfect. Other times, it collapses, and it happens to the best of artists. That’s the human part of it. It’s what makes the work so valuable. Nothing is guaranteed.”

Featured in our January/February 2020 issue.

You Might Also Like