England’s Peak District Has Charming Gardens, Country Homes, and Rugged Landscapes

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Explore stunning natural wonders and fascinating Tudor history on a trip to England’s Peak District.

William Craig Moyes

A sheep at Winnats Pass, in Peak District National Park.Across the street from the great curve of golden sandstone that is Buxton Crescent, against a backdrop of tiered gardens rising toward a war monument, sits a small stone fountain: not the kind that cascades, but the kind you drink from. St. Ann’s Well is so understated, so overshadowed by the crescent’s astonishing 18th-century façade, that I’d spent 24 hours in the town before I noticed it — and that was only because people kept approaching to fill their containers.

The contrasting size and impact of these two stone structures is misleading, because the Crescent, which reopened as the 81-room hotel Buxton Crescent in October 2020 after a mammoth $80 million restoration, would not be there without St. Ann’s Well, part of the natural thermal springs bubbling unseen beneath visitors’ feet. Rainwater spends 5,000 years trickling through subterranean heat, then emerges at 80 degrees with, apparently, marvelous rejuvenating properties.

William Craig Moyes

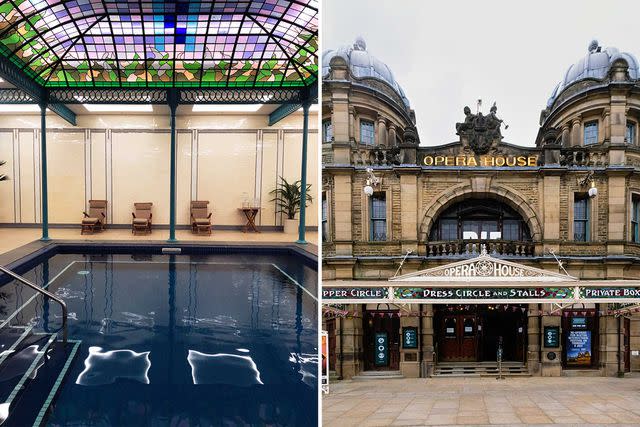

From left: The thermal pool at the hotel Buxton Crescent; Buxton Opera House.I thought I had come to Buxton, a town 25 miles southeast of Manchester, in the county of Derbyshire, to travel five centuries back in time — not five millennia. I have long been fascinated by a number of Tudor women who spent time there, including an imprisoned queen and a powerful countess. But it turns out that this health-giving water, renowned since at least Roman times, trickles through everything. England would not be England without it.

Buxton is almost entirely encircled by the Peak District, the United Kingdom’s first national park and one of its loveliest. The area is well named: the roads tilt around high hills, their patchwork of green dotted with lambs in late spring. When Mary, Queen of Scots was placed in the custody of the Earl of Shrewsbury in 1569, she was just 26 and loved to temporarily escape her imprisonment on his property by riding over these wild lands. Over the course of 18 years, as Mary’s cousin and jailer, Queen Elizabeth I, remained implacable and her hopes of freedom faded, she became ever more sickly, and there’s a plaque on the wall of Buxton’s Old Hall Hotel commemorating her many visits to “take the waters.”

Related: 10 Amazing National Parks in the United Kingdom

The town really became fashionable when William Cavendish, fifth duke of Devonshire, cannily built the Crescent, a complex of hotels, in the 1780s — a deliberate attempt to take advantage of the emerging rage for spas. (The Crescent’s perfect Georgian arc is an imitation of Bath’s Royal Crescent, which was finished the decade before.)

Early wellness had a lot in common with the modern kind. The Natural Mineral Baths on one end of Buxton Crescent, the New Baths (now a shopping mall) on the other, and the elegant marble Pump Room opposite all demonstrate that beautiful surroundings were considered as important for curing the sick as water that “in winter...is as warm as new milk” and “performs many miracles,” as the topographer William Worcester, visiting in 1460, had it.

This health-giving water, renowned since at least Roman times, trickles through everything. England would not be England without it.

Today, the hotel spa is a fabulous underground grotto with three saunas, a cave made from blocks of salt (excellent for clearing the airways, apparently), and two indoor pools — plus a third, partly open-air, on the roof. One pool contains actual Buxton thermal water, heated above its natural tepidity, where guests can soak beneath an elegant decorative canopy of colored glass. “I like to think the blue is the water and the green is the Derbyshire hills,” said the attendant, looking up.

Glass in Derbyshire has an importance all its own, as I quickly discovered. A short walk through the pretty Pavilion Gardens brought me and my husband, Craig, to the double-story glass Pavilion Café. Both were designed by Joseph Paxton, head gardener to the sixth duke of Devonshire.

At Chatsworth House, the Devonshires’ family seat 16 miles east, Paxton created a conservatory that was at the time the largest glass building in the world, and the prototype for London’s Crystal Palace. That achievement was hard for me to appreciate — I’m probably jaded by giant glass museums and skyscrapers — until I went to Hardwick Hall, which stands 30 miles to the east and was built by the duke’s ancestor Elizabeth of Hardwick.

William Craig Moyes

From left: Hardwick Hall, built by Bess of Hardwick in the 16th century; Stella Kisob, chef-owner of Stella’s Kitchen, an Afro-Caribbean restaurant in the village of Eyam.

Elizabeth, known as Bess, was the original reason I had wanted to visit Derbyshire. Born in the 1520s to a small landowner who died before she was one year old, Bess worked her way up, via four marriages and numerous clever investments, to become Countess of Shrewsbury — after the queen, the most powerful woman in England. Immensely intelligent, she turned every setback to her advantage, in an era when women, barely educated and with few legal rights, weren’t supposed to display any brains at all.

Bess was both adaptable and tough, and in this she resembled her native land. The Peak District is part porous limestone, part unyielding sandstone, and those warm springs are forced to the surface at the point where the two meet.

Before seeking her out, I went walking on that sandstone — partly because it is outstandingly beautiful, but also because it’s a route back into England’s past. That warm, bubbling water didn’t just soothe royal bones: since it never froze, it made this the ideal place to build the earliest water-powered factories. And so, a century after my Tudor women died (Mary beheaded for treason in 1587; Bess of natural causes in 1608, at the then-impressive age of 81), men began constructing the Derwent Valley mills that helped to power the Industrial Revolution.

I thought I had come to Buxton, a town 25 miles southeast of Manchester, in the county of Derbyshire, to travel five centuries back in time — not five millennia. I have long been fascinated by a number of Tudor women who spent time there, including an imprisoned queen and a powerful countess.

Derby is the southern gateway to the valley, which runs north through the park; the city’s mills are now a unesco World Heritage site. The Derby Silk Mill, built in 1721 by Thomas and John Lombe, is widely regarded as the world’s first factory. Beside the river Derwent, the mill still looms, a gargantuan brick structure now topped and flanked by glass additions. John Lombe went to Italy to steal the silk-makers’ secrets — early industrial espionage — and increased production to millions of yards of thread a day. The factory was always a tourist destination: Daniel Defoe visited, as did Benjamin Franklin. In 2021, the mill, which had been gutted by fire in 1910, reopened as the Museum of Making, a place that combines the newfangled (interactive tourism) and the old-fashioned (actually building things) in a manner reminiscent of those early industrial pioneers — if without the exploitative working conditions.

On our visit, we saw a giant “grasshopper beam” steam engine from the 1850s (so called because the mechanism resembles the insect’s hind leg) and an early-20th-century loom with spools of cotton still attached. A brass microscope had belonged to Charles Darwin’s grandfather, and a modern artwork was inspired by thread. The concept of making was everywhere: in the many on-site workshops; the full-size airplane engine, built by Derby-based Rolls-Royce, suspended from the ceiling; and in the mill itself, rejuvenated with the help of more than 1,000 volunteers. “Five people cleaned eleven thousand bricks!” Hannah Fox, Derby Museums’ director of projects and programs, told me. In our era of declining industry, it was as exhilarating to witness this creativity as it was to gaze down at the powerful river that started it all.

William Craig Moyes

From left: A white-peach choux pastry at Fischer’s Baslow Hall; Fischer’s dining room.

Nothing in Derbyshire is terribly far from anything else: Derby sits a mere 30 miles from Buxton. So I hatched a crazy plan to cycle along the Monsal Trail, a converted railway line just east of Buxton, to Chatsworth, then follow the roads north to the village of Eyam and picturesque Hathersage. (The novelist Charlotte Brontë stayed in Hathersage in 1845 and drew inspiration for Mr. Rochester’s house in Jane Eyre from a slightly sinister mansion, North Lees Hall, that still stands.) Yes, it would take more than four hours, not including stops for sightseeing and lunch, but it used to take Bess of Hardwick a week to reach London.

Three things deterred me. The first was Craig’s expression: it seemed possible that he, like Mr. Rochester, was considering locking me in an attic. The second was the sneaking suspicion that a place called the Peak District might not prove ideal for a fair-weather cyclist. The third was the tip that I should not leave Derbyshire without eating lunch at the restaurant of Fischer’s Baslow Hall hotel. Sheepishly, I downsized to just the Monsal Trail, an easy 8½-mile bike route. As I biked along, I found that human productivity collided with nature’s industry. Steep banks of moss, fuchsia orchids, and cascades of pink-white hawthorn blossoms alternated with chilly tunnels bored through the hills for the trains. We pedaled across Monsal Dale, a limestone gorge, via a 300-foot viaduct, and paused to look down at Cressbrook, another early factory, a giant white presence in the next valley. The ride was lovely — and flat. And it did not interfere with lunch.

More Trip Ideas: Ravishing Landscapes, Ambitious Restaurants, and a Stylish New Hotel in England's Lake District

We ate extremely well in Derbyshire: cream teas at the Devonshire Arms pubs (there are three within easy reach of Chatsworth); Bakewell’s famous sponge pudding in the ludicrously beautiful village of Little Longstone, a few miles north of Bakewell; modern tapas at the Cow, a low-beamed pub with rooms in Dalbury, near Derby; even a superb goat curry at Stella’s Kitchen, a charming Afro-Caribbean restaurant just a mile away from Eyam. The village itself was poignant, with its plaintive plaques, sprouting among the cottage gardens’ tumbling flowers, that tell the story of an outbreak of plague in 1665 and of the Reverend Mompesson’s heroic decision to quarantine his parish to protect everyone else. A third of the inhabitants died. There is still a hollowed-out stone where parishioners left money dipped in vinegar, the 17th century’s hand sanitizer, in exchange for food.

I hatched a crazy plan to cycle along the Monsal Trail, a converted railway line just east of Buxton, to Chatsworth, then follow the roads north.

Still, none of our good eating prepared me for Fischer’s Baslow Hall. Within this elegant stone manor house, in a sunlit bower where painted birds and plants crept up the wallpaper, each exquisitely presented dish was paired with an unusual yet perfect wine by sommelier Matt Davison. I had known that this sort of lunch would be incompatible with a full day of cycling; I had not realized how the afternoon would flow past in a hazy, delectable stream, until we were too late to visit Chatsworth, despite its being just three miles away. Bess of Hardwick, I feel, would not have approved. But then, even with all her wealth, I doubt she ever ate a meal like that one. The modern world does have a few things to recommend it.

Fortunately, Chatsworth was still there the following day. Back in our car, we rounded a bend past Edensor village to be confronted by a vast structure of golden sandstone surrounded by more than 100 acres of gardens, including the first duke’s fountain, where each of the steps varied to alter the sound of the falling water, and the labyrinth that replaced Paxton’s conservatory, which was so expensive to maintain that it was deliberately blown up after World War I.

The treasures were dazzling: a gigantic fountain built to wow Czar Nicholas of Russia on his planned visit, and the beautiful malachite urns he sent as an apology for not showing up; dizzying ceiling murals; the magnificently detailed Devonshire Hunting Tapestries. At one point I trotted swiftly through a small room and had to reverse sharply: amid various animal drawings, I spotted a Rembrandt.

William Craig Moyes

Higger Tor, a rocky outcrop near Hathersage, in Peak District National Park.Sixteen generations of Cavendishes have lived at Chatsworth. But I couldn’t detect Bess, who married into the Cavendish family in 1547, anywhere — perhaps because the house she built was pulled down and replaced with this 175-room one. Nor was she discernible in Edensor chapel, despite its ornate memorial to two of her sons. I walked up the graveyard’s slope, past Paxton’s tomb, to pay my respects to Kathleen Kennedy Cavendish, who married the 10th duke’s heir and died in a plane crash in 1948. A plaque commemorated her brother JFK’s visit in 1963, just months before he was assassinated.

I finally found Bess, or at least her charismatic ghost, at Hardwick Hall, described as “more glass than wall” because of the size and number of its windows. Beneath a roof that displayed Bess’s initials on every turret, I walked the 167-foot Long Gallery, thinking about the determination required to use so much of one of Elizabethan England’s most expensive building materials, and the hardheadedness with which she judged her son-in-law’s glassworks to be problematic — eventually she set up her own. If she’d lived a century later, she could probably have started the Industrial Revolution on her own. Like quietly bubbling St. Ann’s Well, she is easy to overlook, yet in their different ways, the warm underground spring and the fiery countess powered the story of Derbyshire, the little-known English county that helped create the modern world.

Where to Stay

Buxton Crescent: A feat of restoration that took nearly 20 years has resulted in a luxurious hotel, with curved corridors and a much-upgraded spa, that would have made the 1789 building’s progenitor, the fifth duke of Devonshire, proud.

Where to Eat

The Cow: Cornish fish and Derbyshire meat, including fine pork crackling (an English pub specialty) make a winning combination at this well-designed Dalbury gastropub with rooms.

The Devonshire Arms at Pilsley: The influence of the duke’s family means there are three pubs with this name, all serving good beer, hearty food, and cream teas. This one (which also has rooms) is actually on the Chatsworth estate.

Fischer’s Baslow Hall: A stunning restaurant in an old stone manor in Baslow that’s now a hotel. The menu features inventive dishes, such as barbecued kingfish paired with sake. Unmissable.

Packhorse Inn: Little Longstone is a gorgeous village with the pub to match: the Packhorse has flagstone floors, delicious food, and better Bakewell pudding (a jam and almond sponge, not to be confused with Bakewell tart) than anywhere in nearby Bakewell.

Stella’s Kitchen: Ebullient Stella Kisob, originally from Cameroon, plates up terrific Afro-Caribbean curries in her Eyam front garden while a Haitian black cockerel stalks past your feet. Bring your own alcohol.

What to Do

Chatsworth House: Tour the magnificent 175-bedroom home of the Duke of Devonshire, set in beautiful gardens on a vast estate.

Hardwick Hall: The house Bess of Hardwick built next to her birthplace, Hardwick is less astounding than Chatsworth but much more approachable.

Live for the Hills: Mark and Jackie Sweeney offer bespoke walks in the Peak District that range from Pride & Prejudice tours (part of the Keira Knightley film was made in the region) to visits to historic villages.

Museum of Making: An enormous, innovative museum and workshop in Derby that opened in May 2021 in a former silk mill that is thought to be the world’s first factory.

Peak District National Park: One of England’s largest and most beautiful parks, between the industrial cities of Manchester and Sheffield.

How to Book

For a thorough tour of Derbyshire — including stately homes with stunning gardens, like Chatsworth — contact T+L A-List advisor Ellen LeCompte. Email: ellen@lecomptetravel.com

A version of this story first appeared in the December 2022/ January 2023 issue of Travel + Leisure under the headline "High Drama"

For more Travel & Leisure news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on Travel & Leisure.