‘It’s an Endless Summer’: What It’s Really Like to Be Captain of a Superyacht

The superyacht industry is arguably the glitziest business in the world, and there is no profession more glamorous than being captain of one of these floating masterpieces.

Not only do superyacht skippers get to travel the world in style, they’re usually paid salaries in the healthy six-figures. They’re also privy to the inner machinations of some of the wealthiest and most powerful people alive, get to command mega-vessels, and match wits with no worthier an opponent than the sea.

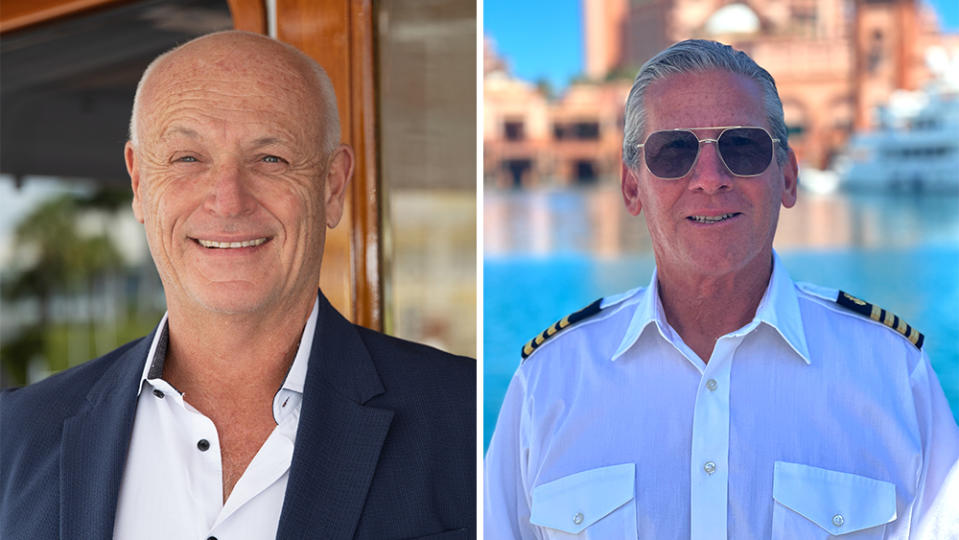

But the road to being top dog aboard a 200-foot Heesen or 450-foot Lurssen is not an easy one. There’s no clear-cut path to the wheelhouse. Robb Report spoke with two captains who worked their ways up the ladder from the lowest rungs.

“I started as a divemaster in Cairns, Australia, where I’m from,” says Capt. Brad Baker of the 146-foot Rena. “Then I was a fisherman and started doing charters on the Great Barrier Reef. I worked every crew job on dayboats and charter boats, evolving with the boats. I came to Fort Lauderdale in 2001, and here I am still, paying taxes in America.”

Click here to read the full article.

Baker’s favorite part of his job: “Getting to change the view and see new destinations. The best thing is that I get to avoid winter.”

Capt. Michael Christian has a similar back-story. He is captain for the Allen Exploration fleet, which puts him in charge of the 164-foot Westport Gigi, that superyacht’s shadow vessel, 181-foot Axis, and 80-foot Viking Frigate. “I came up the hawse pipe,” he jokes.

The former paratrooper started in the merchant marine as an able-bodied seaman, working his way up to become a mate and eventually a master. After running a casino ship, he was hired to captain (and chef) a 156-foot Trinity, before eventually winding up with Carl Allen’s outfit—the three-vessel fleet supported by a Triton submersible, Citation X+ jet, an Icon A5 amphibious plane, and many more support vessels and tools. Christian oversees everything.

What looks like a haphazard career path in any other industry makes sense in the superyacht sector, given the wide-ranging differences between yacht types and ever-changing technology. Switching yachts in ever-greater hull lengths is more than just upsizing boats. It means learning how to work with larger and more diverse crews (the larger boats have engineers, chefs and other specialists), using electronics more common on commercial ships than pleasure boats, and having larger, more complex, engine rooms to deal with.

In the pilothouse, both men point to the sweeping banks of electronics across their helm stations as proof of the complexities of the job. “We have a commercial-grade Wartsila Transas NS4000 plotter that is standard for larger ships,” says Baker, then pointing to the redundancies of other systems. “We also have two radars, double depth sounders, and bow thrusters. For communications, we have satcom, AIS, VSAT, and are GMBSS compliant. The farther offshore you go, the more you need.”

Even with all the state-of-the-art equipment, the boat has paper charts—it’s old school, like someone carrying a roadmap in their car in case their phone goes out. “We never use them,” says Baker. “But it’s another level of security just in case.”

The other thing about superyachts: Technology changes so fast that systems need to be replaced. Baker says the entire pilothouse will undergo a revamp at the end of the next season, with hundreds of thousands of dollars in new electronics replacing the older equipment. “It’s time,” he says.

One piece of equipment that Christian’s Gigi has that Baker is considering for Rena is Starlink. That satellite service will offer seamless worldwide streaming coverage within the year, meaning Gigi could soon conceivably have an uninterrupted screening of Jaws while bobbing in the Weddell Sea in the Southern Ocean, thousands of miles from civilization.

Christian’s job faves are sunrises and sunsets in calm ocean, especially with whales or dolphins in the water, mentoring new captains and, surprisingly, maneuvering in tight quarters. Imagine driving that massive, 20-ton superyacht around a crowded marina, just feet away from other yachts with a collective value of billions. Unlike the highway, water is slippery and marinas are prone to winds and currents that can make docking a nightmare.

“Moving something that’s 180 feet long is challenging,” admits Christian. “But it’s a blast. When I was young and wanted to be a captain, it was just so I could do this. I’m behind the wheel and people are calling the distance between our boat and the dock or other boats. Everyone’s watching. At times, you have six inches to maneuver. It’s crazy but it’s so satisfying.”

Both captains say docking in the Mediterranean is especially challenging. Typically yachts in Mediterranean ports back into slips, sometimes literally pushing their neighbors out of the way with their fenders.

“You often need to wiggle your butt in,” says Baker. “It’s a little scary. When you’re a first mate you don’t get a lot of wheel time, so you don’t necessarily have much docking experience. Then you become captain and the first time you do it is a leap of faith. It might be blowing 30 knots and the current will be running across the marina, but there’s no one to help you. You’re in charge.”

Which is really the bottom line for any captain—they are fully responsible for a huge, bulky, beautiful machine as well as the crew that makes it function. It’s a responsibility that neither man takes lightly. Both list firing crew as one of the biggest drawbacks to the job. “Running crew in general can be tough because they’re often from different countries and they’re living in a boat jail,” says Baker. “You need to work on your conflict resolution skills to try to keep everyone as cohesive as possible.”

Other negatives, according to Christian, are rough weather at sea, which is when guests get seasick, and missing his wife and children on holidays “or when something cool happens,” like birthdays or graduations.

But for both, the captain’s lifestyle has been worth it. “What other job do you get to see these stunning destinations, where the view is always changing?” says Baker. “We migrate with the birds. When they leave, so do we and follow them. It’s an endless summer.”

Best of Robb Report