‘The end of George Michael’: how Praying for Time led to one of the most savage feuds in pop history

It was, by every measure, a curious choice. In the summer of 1990 George Michael was preparing for his big comeback. His debut solo album Faith had just sold 20 million copies and turned the former Wham! singer into a global pop superstar.

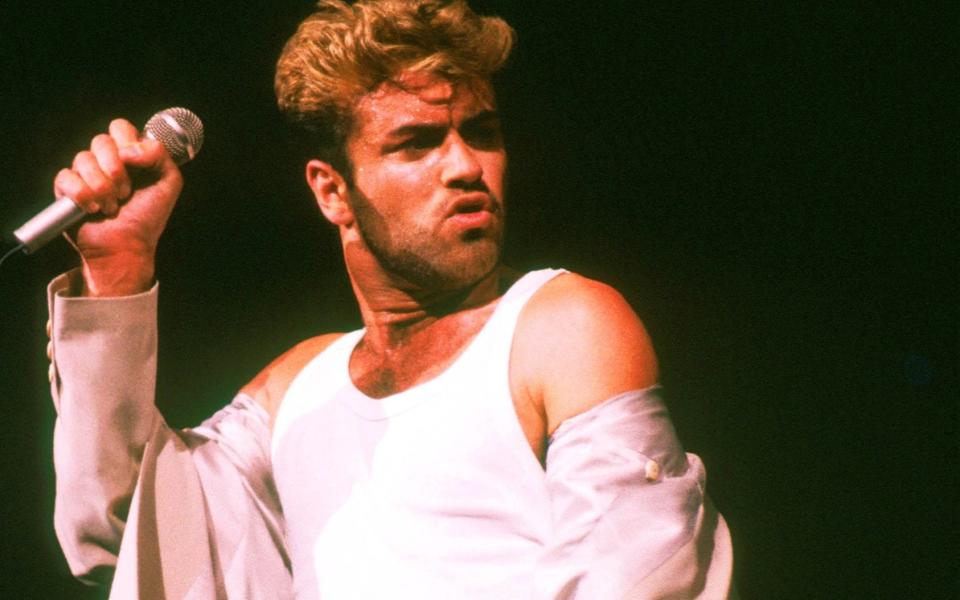

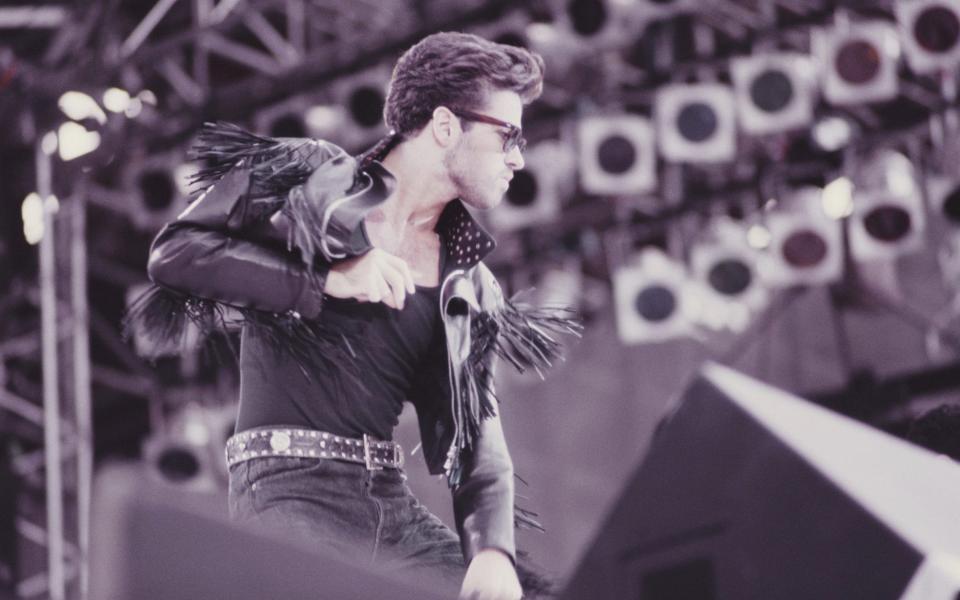

With songs such as I Want Your Sex (Pts 1 & 2) and the album’s title track, the singer from East Finchley had propelled himself into a music superleague populated only by Madonna, Michael Jackson and Prince. Further, the designer stubble, mirrored Aviator shades and leather jacket that Michael wore in the Faith video had turned him into a stadium-filling sex symbol from Tokyo to Tampa Bay. Aged just 27, the world was at his feet. And then he released Praying For Time as his comeback single.

A funereal ballad about the world’s ills with no obvious pop hook or chorus, Praying For Time baffled even those close to the singer. “It was unlike anything he’d done before,” recalls Pete Gleadall, a trusted member of his band and currently the Pet Shop Boys’ musical director. “It’s quite funny, you’ve got I Want Your Sex and then you’ve got Praying For Time. You think, ‘Is that the same person?’”

But the bleak song – released 30 years ago today, on August 13 1990 – wasn’t Michael’s only curveball to the world. He refused to put his picture on the record sleeve and declined to appear in its video, a sacrilege in the glory days of MTV. The star’s deliberately obtuse decisions presaged one of the most bitter fallouts in pop music history.

Desperate to shed his image as a sex symbol and be taken seriously as a musician, Michael wouldn’t let his name or image appear on the cover of the album that followed, Listen Without Prejudice Vol. 1. He refused to promote the record, and didn’t tour as he had done with Faith. The largely acoustic album was a downtempo collection of grown-up soul (seven of its 10 tracks were ballads) and it performed badly in the US compared to its predecessor, selling fewer than a third as many copies.

Listen Without Prejudice’s relative commercial failure led Michael to sue his record label Sony. He accused them of failing to promote the album as punishment for him downplaying his "gorgeous George" dreamboat image and failing to deliver them a more poppy sounding Faith Mark 2.

The ensuing case at London’s High Court struck at the very soul of the record industry: it was about artist versus label, freedom versus control. Michael tried to wrestle ownership of his songs back from Sony and claimed his contract was tantamount to “professional slavery”. Sony argued that “chaos” would follow if Michael won, ceding an unprecedented shift in power towards artists.

Michael lost the case, and his career never recovered. He wouldn’t release another album for six years or tour for another 15.

As professional meltdowns go, it was as spectacular as it was public. The court case marked “the end” of George Michael the superstar, says his former publicist Michael Pagnotta. And yet the entire farrago was driven by Michael himself. “This was a wilful destruction. It was an implosion not an explosion,” Pagnotta explains to me.

But time has shone a forgiving light on the saga. Fans of Michael, who died on Christmas Day 2016 aged 53, may always wonder what might have been if the singer had released albums in those fallow years. But to most objective observers, this isn’t important. Today, 30 years on, Listen Without Prejudice is rightly seen as a masterpiece. By not bending to pop’s fickle breeze in 1990, it sounds timeless.

Everyone from Liam Gallagher and Elton John to Mary J. Blige and Mark Ronson laud the album. Praying For Time is worthy of John Lennon, says Gallagher. The album has an ethereal mystery about it, says John. And the court case, although unsuccessful, at least highlighted to other artists that taking a stand against labels was a principled thing to do. The period was a shocker for Michael, no question. But in many ways it proved him a trailblazer.

The 1988 Faith tour was gruelling. Michael played 109 shows across 16 countries under the intense glare of the world’s media. Fans’ unrelenting attention left him exhausted, unhappy, lonely and lacking what he later called “mental balance”. It was his first solo tour: at least with Wham! he had bandmate Andrew Ridgeley to share the rollercoaster with.

Gleadall was on the tour with Michael as his programmer. It was the early days of music sampling, and Gleadall’s job was to sit underneath the stage with boxes of floppy discs and reproduce Faith’s distinctive sounds in a live setting (including the ickily-suggestive synth squelches on I Want Your Sex).

“He found the whole Faith tour quite a struggle. It’s a lot of pressure on one person to go out there. He was also a straight sex god at that point [he’d yet to come out as gay], which again must have been a struggle. It’s enough to send you mental,” says Gleadall. By the end of the tour, which Michael said had driven him “to the edge of madness”, he’d decided that stepping off the promotional treadmill for his next album was the only way to save his career in the long term.

Sessions for Listen Without Prejudice started in engineer Chris Porter’s house near Guildford before moving to Metropolis Studios in Chiswick. The recording process tells you everything you need to know about Michael’s uncompromising approach to his music. He’d never been a pop star, not really: he was a serious recording artist. He wrote, arranged and produced the songs himself (apart from a cover of Stevie Wonder’s They Won’t Go When I Go), starting with a drumbeat or a sound in his head and building the compositions slowly from scratch. So singular was his vision that progress was glacial.

“He’d stab about on the keyboard to find the notes he’d have in his head and I’d record the performances, often a chord at the time,” Gleadall says. Sometimes when Michael had gone home, Gleadall would re-record the patchwork quilt of chords to make it sound like they’d been played together. Michael constantly toyed with songs’ tempos, would often crash studio computers with his tinkering, and when it came to recording vocals he’d drop them in a word – and sometimes a syllable – at a time.

So idiosyncratic was the drum pattern in his head for hazy jazz number Cowboys and Angels that even a professional drummer couldn't nail it. Gleadall and Porter had to record the drummer’s efforts, cut up the individual beats, and stitch the pattern together using technology. “It took a long, long time to do anything,” says Gleadall, who was left staggered at Michael’s willpower and creativity.

The variety of textures that emerged was astonishing. Although slow, the album featured soul, jazz and gospel, piano ballads and panpipes, funk grooves and flutes. Early flirtations with house music were binned but flashes of the genre remained in the deceptively simple piano part of Freedom 90. James Brown’s Funky Drummer sample – red hot at the time, favoured as it was by Public Enemy and The Wild Bunch – was used on the three uptempo tracks (which, unsurprisingly, have dated the most).

Lyrically, the singer’s desire for artistic independence infused everything. Freedom ’90, the album’s third single, was a howl for liberation. “Today the way I play the game has got to change / Now I’m gonna get myself happy,” Michael sang. In the song’s David Fincher-directed video – which famously featured five supermodels but not Michael – his Faith era leather jacket was set on fire and a jukebox similar to the one he leant against in the Faith video was blown up. The symbolism was clear. Those days were gone.

Listen Without Prejudice performed well in the UK, outselling Faith. But in the US it entered the charts at number 22 and stayed there for less than half the time Faith did. The last two singles from the album failed to chart altogether. Sony were aghast at what they called Michael’s “bombshell” decision not to promote the album (which he later likened to “prostituting” himself). Frank Sinatra even wrote him an open letter, effectively telling him to grow up and get over it.

But Ol’ Blue Eyes couldn’t sway young George. It’s easy to see Sony’s side. Two years on from being the world’s biggest selling artist, Michael had delivered a difficult album with no obvious hits that he was refusing to help sell. Other reasons may have been at play. There was talk of personality clashes between Michael’s UK and US teams. And Sony’s priorities could have been elsewhere: it may just be coincidence, but Sony released the far-more-marketable debut album by Mariah Carey just three months before Listen Without Prejudice (Sony boss Tommy Mottola went on to marry Carey in 1993).

Michael was bruised that the label for which he’d made millions was not buying into his artistic journey. “I didn’t want to pick a fight,” he later said. “I just wanted to work with people who wanted to work with me and who would have some respect for the fact that I was growing up.”

According to Pagnotta, things came to a head in a phone call between Michael, his manager Rob Kahane and a senior suit at Sony. “It got really hot. I can’t tell you verbatim but there were some insults traded. And threats. And at the end of that phone call, from what I was told, George told them that their relationship was impossible to repair,” he says.

To the singer, suing Sony was the only logical next step. If the label weren’t playing ball then he wanted his master recordings back. They were his songs and his property, he figured. Not so, said Sony. They’re ours. Michael was no doubt buoyed by a previous litigation. In 1984, he and Ridgeley successfully sued their label Innervision over a dispute about Wham! royalties, having signed a terrible deal as unknowns in 1982. A distrust of labels lingered. But this was on a far greater scale.

Panayiotou and others v Sony Entertainment (UK) Ltd. – the case used Michael’s real name – started at London’s Royal Courts of Justice High Court in October 1993. In legal terms, Michael argued that his agreement with Sony amounted to an “unreasonable restraint of trade”. The case made the national evening news on the day it opened. Pagnotta would accompany Michael to court when possible. He says the singer was justifiably nervous on the morning of his testimony and paced around a court anteroom. “I said, ‘George, how are you doing?’ And he said, ‘To tell you the truth, I’m shitting myself.’”. The singer then said that he wished he had “a bottle of Jack [Daniels] under the stand”.

But no amount of Dutch courage would have saved him. In the summer of 1994 Michael lost his case on every count. Justice Jonathan Parker ruled that his Sony contract was “reasonable and fair”. Although he lost a reported £4 million in legal fees, the singer vowed to appeal. In reality, he stood no chance. “George was too successful to make his case,” says Pagnotta. Many observers agreed: the legalities aside, it was hard for ordinary people to have sympathy for a millionaire rock star stamping his feet about injustice.

During and after the trial, Michael roamed in a musical no man’s land. Unable or unwilling to release songs himself, he coasted as a vocal gun for hire. Despite this he still enjoyed some of his biggest hits during this period in a series of live duets: Don’t Let The Sun Go Down On Me with Elton John and Somebody To Love with Queen. He also donated three upbeat tracks, including Too Funky, to Aids awareness album Red Hot + Dance. The songs were initially earmarked for a high tempo sequel for Sony called Listen Without Prejudice Vol 2. It was shelved.

But his career never recovered. Music mogul David Geffen bought Michael’s contract from Sony in 1995 and he released the acclaimed Older album the next year. Inevitably, many fans had moved on. “It’s not so much that people blamed George, I just think they kind of stopped paying attention,” says Pagnetta.

The singer later admitted in a documentary that his legal action was “a complete waste to time and I regret it to this day”. Pagnotta is not so sure. “I mean, everybody has some regret about losing millions of dollars and losing a very public court case. But I don’t think it was something he wouldn’t have done again.”

And yet if the legacy of this knotty story was Listen Without Prejudice, then it was pain worth bearing. The album sounds better as the years go by, as if it has grown into its own world-weariness. And in standing up to for artists’ rights, Michael has proved an inspiration to fellow musicians. Everyone from Prince to Taylor Swift have tried to regain ownership of their master recordings from record companies. Michael showed them the way.

“The truth is, artists are so much more empowered today, and a lot of people owe that to George Michael,” says Pagnotta. “He took the stand and he paid the money. So maybe he changed things for everyone.”