‘These Embryos Are Five Years’ Worth of Money, Sadness, and Hope. I Just Want to Be a Mom’

The Alabama Supreme Court ruled last week that frozen embryos are legally considered children, which effectively banned IVF treatment in the state. Following the ruling, several fertility clinics in the state, including the University of Alabama at Birmingham health system, paused IVF treatment due to fears they could face criminal or civil prosecution.

The ruling and its aftermath left thousands of people who are currently undergoing IVF treatment in a devastating limbo, adding even more stress, panic, and heartbreak to what is already a grueling endeavor. Two of those affected are 32-year-old Abbey Crain and her husband, Colby, who have been undergoing fertility treatment for more than five years.

Crain, a journalist and artist who lives in Birmingham, has spent the past several years reporting on the loss of women’s rights to their own bodies in Alabama while dealing with the mental and physical toll of her own private fertility journey. She and her husband had been preparing to transfer their frozen embryos from their latest egg retrieval when she heard the news about the state Supreme Court’s decision.

“It’s insane,” she says. “While I don’t view my embryos as scared children sitting in the freezer calling for their mommy, I do feel that they are mine and no one else's. And right now I can’t, can’t touch them physically, mentally, spiritually, if I wanted to. I legally can’t.”

Here, Crain shares her story in her own words, from the hard-fought road she has taken to get her embryos, to why women in every state need to stand up and fight back against the latest gross incursion on the right to our own bodies.

My husband and I have been trying to have a child since 2018. We were sent to a fertility specialist after trying for a year and being unsuccessful. It just so happened that my first IUI [intrauterine insemination] corresponded to Alabama banning abortion in 2019, and I was covering it as a journalist. So I was taking fertility meds while driving to the Alabama State House in Montgomery, and then watching men in the State House fumble over their words on how a baby is made. The disconnect was insane.

We started gearing up to do our first round of IVF in the spring of 2022, right before Roe was overturned. I was still writing about reproductive justice and begging for people to pay attention, but I also knew the decision was inevitable. And I was like, You know what? I can't do this at the same time. I can’t do it. I stopped writing altogether and pivoted to other jobs in my newsroom. Then, that summer I did two rounds of IVF that were unsuccessful.

Not everyone knows what IVF is like, but many people know what it’s like to wait and want for a kid. Often, it’s all-consuming. It’s full of grief, it’s full of hope, it’s full of pain. When that’s where you’re at, that’s everything in your mind. You’re dreaming, you’re planning. I’ve gone back and forth over these last years—I’ve literally lost count of how many—hoping and dreaming and planning for my future. Then trying to tell myself I need to not focus on this. I need to put something else first so I don’t think about it.

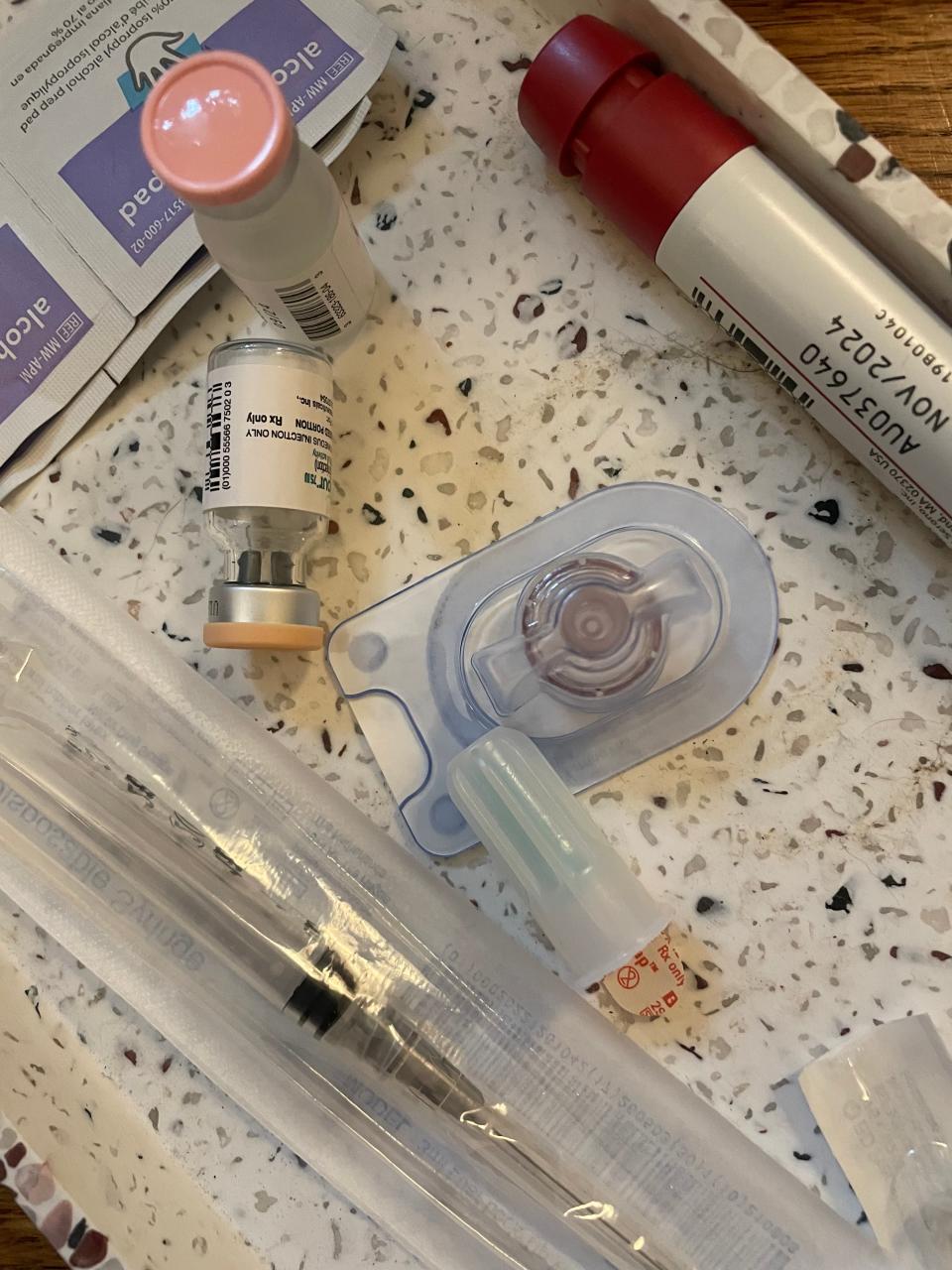

It’s been hell. I have been through war with my body. I’ve been through an unmedicated egg retrieval, which was terrible. There’s been the weight gain. There’s been the emotional side. I’ve dealt with mental health issues my entire life, and having to adjust my mental health medication along with this and how it affects my brain, I gaslight myself the whole time. It’s not fun, and it’s extremely expensive.

Not everyone knows what IVF is like, but many people know what it’s like to wait and want for a kid.

My last retrieval was in the fall, and we hadn’t scheduled an embryo implantation date yet. We were waiting for life stuff to align. I literally saw the news about the hospital pausing treatment on an Instagram post this week. I was like, Wait, hold on. I went to my husband, Colby, and I showed him it, and burst into tears.

In every stage of this journey, I’ve been hopeful and emotional, and full of yearning. And then other times I’ve had to put it away, put one foot in front of the other. That’s how I was when the ruling came, but hearing the news about our fertility clinic opened everything. I started screaming. I was so angry. I was so angry that this man, Jay [Mitchell, the Supreme Court justice who wrote the decision], who lives five miles down the road from me, goes to a church that people in my circle go to, and has children in schools in my community, has more of a say in whether and when I get to be a mom than me. That’s where my mind went. After all of this, it’s come for me. So many women have been feeling this. So many people with a uterus have been feeling this, that their literal rights are being stripped away.

It’s not just theory anymore. They can’t have an abortion. They can’t have their miscarriage managed in the way they want to. And it’s not the doctor’s decision. It’s not their partner’s decision. It’s not their decision. It is now the state’s decision, and that is enough to make me want to light everything on fire. When I found out, I called my best friend Sarah. She drove home from work and picked me up and drove me around and got me lunch, and we sat outside discussing our options. Should we protest in front of this man’s house? Could we organize? Or would it be enough to simply tell my story, how I want to? I’m still a journalist. I want to channel my rage into something, because otherwise I feel like I’m going to explode.

I want people reading this who don’t live in Alabama to know that you are not special and you are not safe. In Alabama we got the same kind of flack that we are getting right now in 2019 when primarily Black women were leading the charge to maintain our rights to an abortion in the South, specifically in Mississippi and Alabama. And then they used the South—Mississippi—to ban it for everybody two, three, years later. That’s the most recent thing, but this has happened all the time. Alabama is the birth of gynecology and the birth of where Black women were experimented upon, and that’s where a lot of our practices still come from.

I want people to know that we’re not backwoods blood-red states who should get what they deserve. Yes, we’re in the Bible Belt, and a lot of powerful people at churches and at the State House have twisted the words of the Bible to fit their Evangelical Christian narrative. And people are moving in fear and people are moving against people actively trying to take their ability to vote away. But I want people to know that while the men here are hell-bent on controlling women’s bodies and LGBTQ+ folks’ bodies and are very explicit about it—and it may happen first here—they live in your state too. They just might not have a Confederate flag flying in front of their house. And the sooner you wake up and join hands with the mostly Black Alabamians doing the work, that is our best bet for saving our rights on a bigger scale. If you’re interested in supporting local efforts for reproductive rights on the ground, check out the nonprofits ARC Southeast, Sister Song, and the Yellowhammer Fund.

While I don’t view my embryos as scared children sitting in the freezer calling for their mommy, I do feel that they are mine and no one else’s. And right now I can’t, can’t touch them physically, mentally, spiritually, if I wanted to. I legally can’t.

I think there are a lot of people saying that pausing IVF wasn’t the intended purpose of this ruling. We’re in the legislative session. There are bills that they’re working on coming up with passing that will make an exception for IVF because this is not the intended purpose. But if that wasn’t the intended purpose, then why did they let it pass? They knew this was going to happen, and if they don’t believe that a life or an embryo in a tube is a child, then show me the line. I want them to look me in my eyes and tell me where the line is. Not just the legislature, but people who believe in this stuff. I want people to know that these are people’s lives you’re messing with.

As far as next steps for my embryos, I can’t even go there yet. I am just mad. I’m hung up on the anger. I don’t care if they remedy this in a week. You have messed with thousands of dollars of medication for people. You have yo-yoed women and people trying to get pregnant, LGBTQ+ couples, who are already in a fraught situation. I thank God that I wasn’t actively on medication and my appointment wasn’t changed. I can’t imagine what those folks are going through and you can’t take that back. Even if they do remedy this, you can’t just move on business-as-usual because that happened. That’s what Black reproductive folks have been saying, that it’s inevitable. It’s by design. It’s like we took a peek behind Oz when we saw what they really wanted, which is control.

These embryos are five years’ worth of money, stress, sadness, hope, yearning. I just want to be a mom. I just want to be a mom and in a state that in its Constitution now says it is a pro-life state. You are actively keeping me from being a mother and I don’t care if you fix it. You’re going to lie in the mess you’ve made.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Stephanie McNeal is a senior editor at Glamour and the author of Swipe Up for More! Inside the Unfiltered Lives of Influencers.

Originally Appeared on Glamour