When Elvis saved America from Polio: how celebrities can help conquer vaccine fears

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

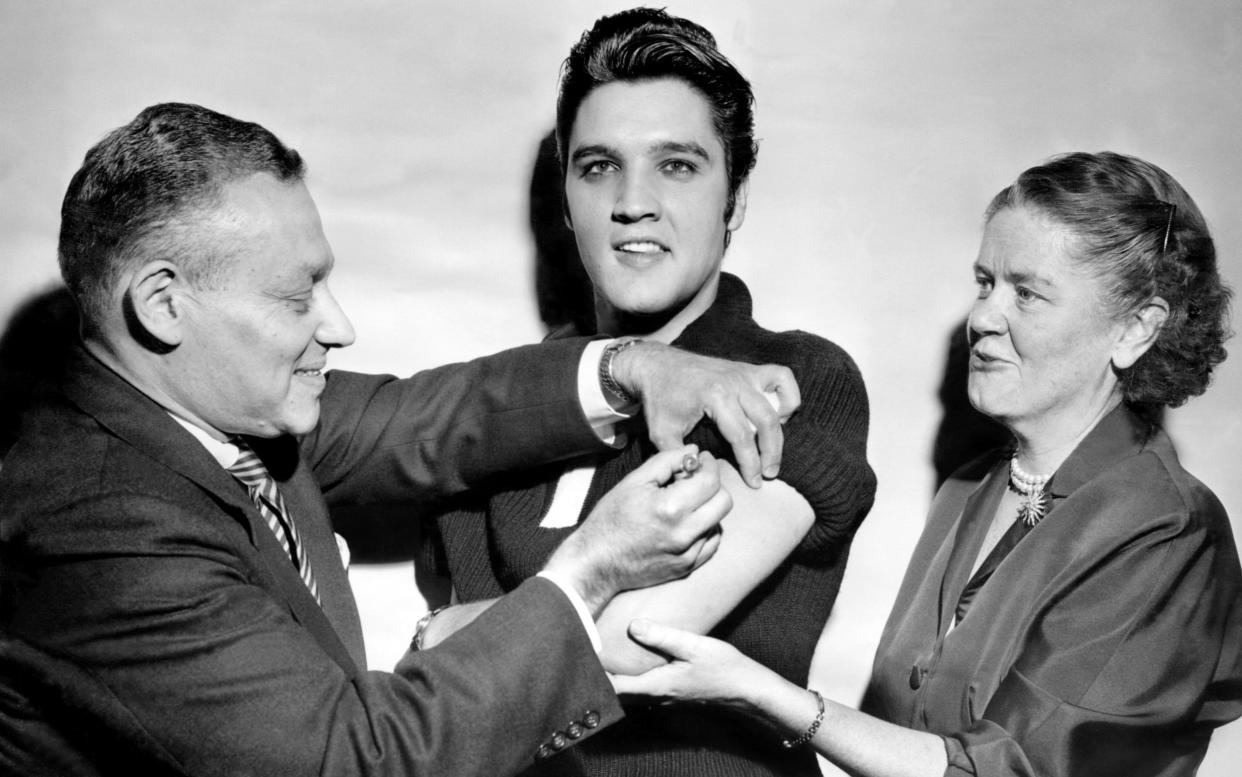

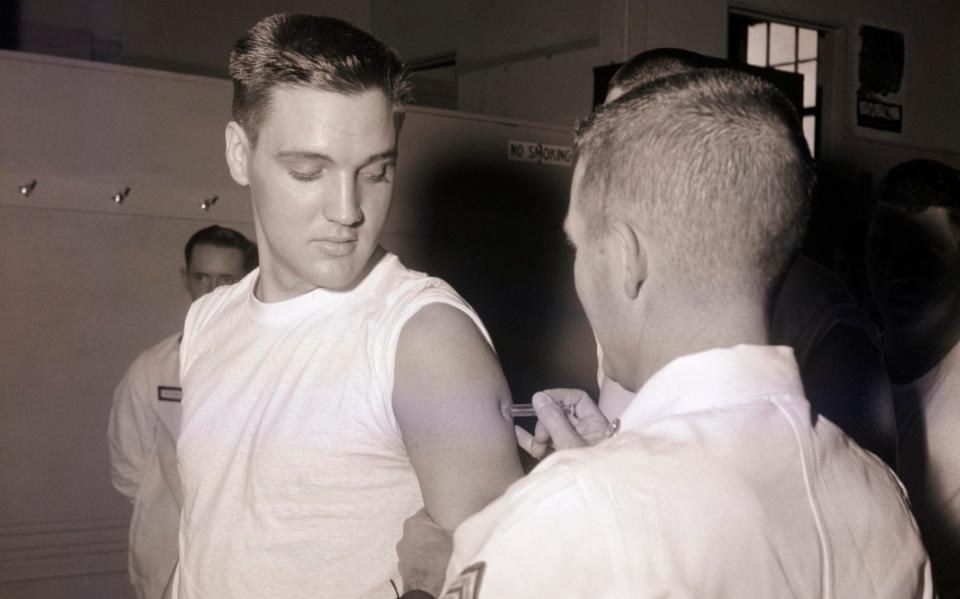

It’s late October 1956, and a man stands on a TV set in New York City. He’s got a toothy grin and a magnificent cock’s comb of brylcreemed hair. There’s a shiver in the air - even now, after only a few hits, the man is a star; his aura palpable. He rolls up his sleeve and bares his arm. A doctor steps smartly forward and sticks a needle in his bicep. Applause - and a sigh from the producers. They’ve got their money shot: Elvis is in the building. Elvis has had the polio vaccine.

In 1956 America was gripped by a Polio epidemic. The grisly disease was a terrible threat to the country's children - in 1954, nearly 40,000 were infected, and 1,450 died. Many who survived were paralysed; they were confined to coffin-like "iron lungs" which pumped breath into their bodies because theirs had failed.

The US government needed widespread take up of the vaccine, which had been developed by University of Pittsburgh virologist Jonas Salk in 1955. Elvis getting the jab on the The Ed Sullivan Show was the coup they craved. The singer’s fame had gone meteoric with the hit Heartbreak Hotel, released in January 1956. "Presley Receives a City Polio Shot," boomed the New York Times. The stunt paid off: a year later, there were just under 5,500 cases, and only 221 deaths. Where The King went, others followed.

Elvis and other celebrities also threw their weight behind the 'March of the Dimes'. They encouraged the public to donate small amounts of money to the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, a health charity formed in 1938 by President Franklin D Roosevelt, himself a Polio victim. The influence of rock 'n' rollers like Elvis, Chuck Berry and Little Richard was used by the Foundation to cut through to teen audiences, tapping into the increasingly differentiated teen culture of dates, dances and soda bars.

A campaign group, Teens against Polio (TAP), was formed. They put on dances with free entry for those who could flash a vaccination certificate; and teens crippled by Polio gave talks at schools to encourage their peers to brave the needle. There was even a move to nudge girls into denying boys dates who didn't get the vaccine - "No shot? No date, buddy."

There’s a tradition of using cultural icons to promote public health messages. It has something to do with the peculiar atmosphere of the 20th century - a combination of the growing cachet of celebrities, a sparse media landscape and widespread acceptance of the idea that the public’s health was worth preserving.

In 1986, the children’s author Roald Dahl wrote an open letter about the death of his daughter, Olivia, aged seven, from measles. She died in 1962, “twenty-four years” before the letter was published. Nonetheless, it is heart-wrenchingly vivid:

“Are you feeling all right?” I asked her. “I feel all sleepy,” she said. In an hour, she was unconscious. In twelve hours she was dead. The measles had turned into a terrible thing called measles encephalitis and there was nothing the doctors could do to save her.

He goes on to ask that “parents insist their child is vaccinated against measles”. No punches are pulled: “What on earth are you worrying about? It really is almost a crime to allow your child to go unimmunised.”

Could similar endorsements work now? The government certainly thinks so. Ministers and the NHS are in discussions about a roster of "very sensible celebrities" to front a public messaging campaign, according to The Guardian. Setting aside the formidable logistical challenges, the main obstacle to comprehensive inoculation is public opinion. In May this year, researchers in the US found that 23 per cent of Americans would refuse any Covid vaccine. And in the UK, a fifth of Britons said they wouldn't take a vaccine, with 2 per cent opposed to vaccines on principle, according to YouGov.

These figures are frightening. The UK lost its "measles-free" status last year. The jump in infections was blamed on a false 1998 claim that the measles, rubella and mumps vaccines were linked to autism.

It's been a tough year to be a famous face. For every Marcus Rashford, successfully brow-beating the government into u-turns on free school meals, there's been a Gal Gadot and her gilded pals: subjecting a house-bound populace to a queasy rendition of John Lennon's Imagine. Celebrity has never looked more ineffective - or hollow.

So who best to lead the anti-Covid charge?

“David Attenborough would be a great role model for the coming vaccination,” believes Professor Susan Michie who advises SAGE’s behavioural sub group. “There is a consistent evidence base on the effectiveness of role modelling on behaviour.”

Professor Stephen Reicher, another advisor to SAGE, is more ambivalent: “I think it’s tricky. The problem is that we now have lots of celebrity anti-vaxxers and so if someone makes a show of getting vaccinated, then it might simply lead to others being more vocal in opposition.”

Fragmented, fractious and fiercely divided: our media landscape is markedly different to that of Elvis’s day. Social media and hyper-partisan news networks amplify fringe views and batty theories. So while Barack Obama could reach his 127 million Twitter followers with a pro-vaccine message, his remarks might turn off an equally large number who intuitively revile him - and anything he endorses.

Conformity theory compounds this problem. As popularised by psychologist Solomon Asch, it argues that consensus is the glue that holds social interactions together. Asch found that people are willing to ignore reality and give incorrect answers in order to conform to the rest of the group.

In addition, notes Professor Reicher: “If just one person out of seven differed, then the effect is greatly reduced. Group consensus brings influence. Break the consensus, and you lose influence.”

A loud-mouthed anti-vaxxer, therefore, might drown out a chorus of earnest pro-vaccination voices.

Lastly, we face the question of messaging. With Elvis’s appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show or Dahl’s letter, there was a clear narrative, a consistent format and an instantly recognisable face. Achieving all those things today will be far harder.

The government’s handling of Covid-19 communications has already proved this, argues Professor Clifford Stott. “‘We need a greater level of clarity,” he says. “We are trying to build agency among people - adherence without compliance. We need a more nuanced approach that understands the relevance of particular celebrities to communities. Will a celebrity have the same effect in working class estates in Bristol? Or West Indian communities in Leeds? The idea that we can do it generically is problematic to say the least.”

A hashtag which celebrities shared on social media might be effective, then. Provided it gained sufficient traction among diverse cultural icons and their respective communities. Or maybe an apolitical figure with truly global reach, like the Queen or Sir David Attenborough, could be seen to get the jab.

Professor Stott warns: “Political opportunists are using the anti-vax agenda to gain purchase in disaffected communities. And when you have the President riding that ticket then you’ve got a bit of a problem.”

Sadly, Elvis ain't coming back. And persuading the public to get vaccinated may pose a greater challenge than logistics. The stakes, though, could not be higher. Sleeves up, Sir David.

Read more: