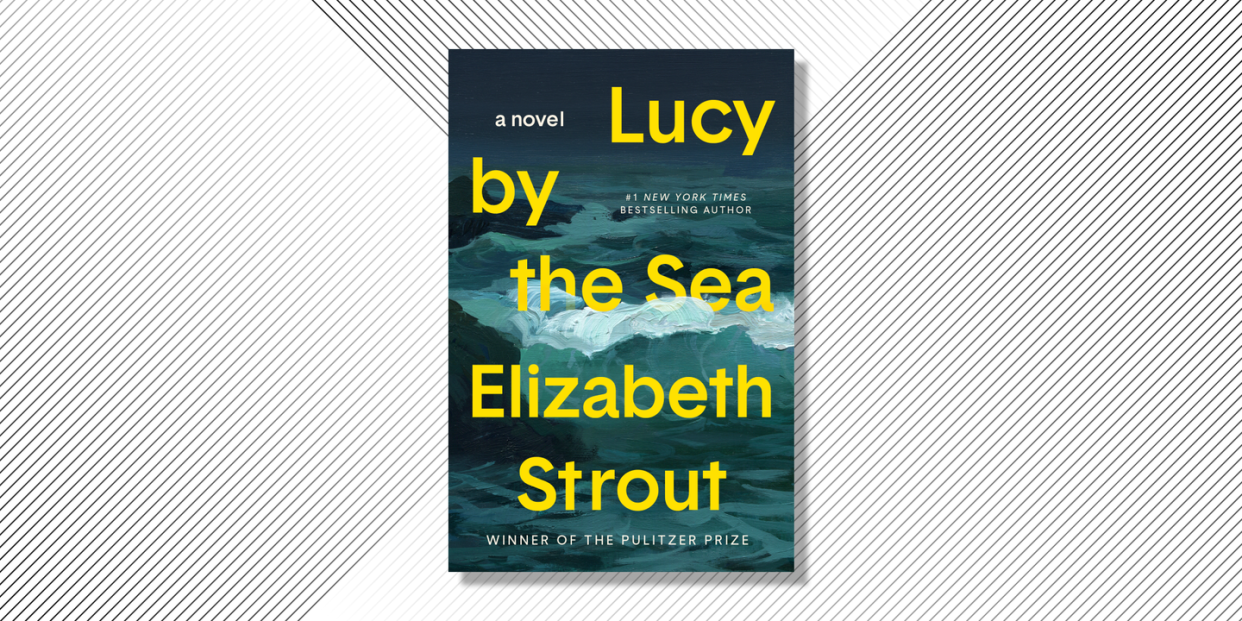

Elizabeth Strout’s “Lucy by the Sea” Is Timeless and Familiar, Like an Old Friend

On the heels of becoming a Booker Prize finalist for her 2021 novel, Oh William!, Elizabeth Strout returns to her iconic character Lucy Barton for her ninth book, Lucy by the Sea, also one of Oprah Daily’s favorite books of the year. Recent widow Lucy finds herself as we all did in March 2020, wholly unprepared for the pandemic. Her ex-husband, William, demands she join him in a rented home in Maine, far from their respective Manhattan apartments. It’s from this removed perspective that Strout tosses us together with these individuals who share two grown daughters, several marriages between them, and a lifetime of history. As they muddle through the days and weeks that made up the early days of the pandemic, so do we. This is a cathartic and gripping novel that explores the depths of our knowledge of others and the lengths to which we will go in order to save the ones we love.

This is, in fact, the fourth book in which Lucy, her friends, and family surface, but please don’t call this a series. Truly, it’s entirely possible to read the books out of order and be completely in sync with the world of these characters. I have done so. It’s a testament to Strout’s clear-minded, direct prose that the reader doesn’t need to strictly follow the plot to empathize with Strout’s characters and their challenges. Like in any relationship, there are times in reading these books when certain stories demand attention, and there are times when personal moments are concealed or suppressed. There is inherent pleasure in that mystery. Her books read like familiar friends: complicated, timeless, achingly human, and compassionate. Strout spoke with Oprah Daily to talk about her writing process and inspiration.

How do your characters develop? Do you keep regular writing hours, or does inspiration strike as you’re going about your day?

Lucy Barton came to me as a voice, much like a thin gold string that was coming down in front of me. I thought, Hmm, if I can hold on to that voice, I’ve got a character here. There’s nothing but her voice to offer the reader, and, to my mind, it was unique. I was very nervous about writing in first person and then very nervous when I made her a writer and so on. But I thought, Oh, let’s just go with it, for heaven’s sake. So I did, and then I realized I wasn’t done with her yet either, because she was so intriguing to me.

I was unloading the dishwasher when all Olive [Kitteridge] to me, but I knew enough even back at that stage that when something comes to me, I need to write it down immediately and do so in a scene because there’s no point in my taking notes and saying, you know, “large woman by picnic table,” because that doesn't have any buoyancy to it. So I have to write the scene as quickly as I can, even if it’s just a paragraph.

Do you keep a notebook on hand?

I have so many different pieces of paper. I’m very disorganized; I’m so embarrassed by how unorganized I am, but I’m not going to change at this point in my life. I just have so many different pieces of paper. I somehow seem to find the right one, if it hasn’t been tossed to the floor.

It’s probably also serendipity, too, if you find what you need. I was wondering how it was that Lucy came to you.

I was just lying on my bed in New York and I sort of started to hear her, so I wrote, like, 30 pages or so, little sketches. I thought I wouldn’t do this because, as I said, I was just nervous about it because it was a different kind of voice and it was first person, but for some reason, I sent it to my editor, [the late] Susan Kamil. I don’t know why, because I never sent her anything before sending it to my first reader or to my agent. And she wrote back immediately; she said, “You have to do this.” She’s the person that gave me permission to—not even just permission, but said, “You must do this.”

How did it ultimately feel right? Has it changed your relationship to writing about writers?

I just realized that I have to get inside Lucy’s head every single time I sit down to work on a Lucy book. This is a woman who stayed after school just to stay warm, and that’s where she would read. And I thought, Oh, my word, these books are going to open up the world to her. And that's why she needs to be a writer. And it made me nervous because I'm a writer, obviously. And I thought, Okay, let’s just see how this works. I liked how it worked out in My Name Is Lucy Barton. And so then I just thought, Okay, she’s a writer. That’s it. You know, she’s not going to be a doctor.

That wouldn’t be true to her at all. At what point during the pandemic did you decide you were going to write Lucy by the Sea? You’d already written three books dealing with Lucy. Were you thinking that you would write another one, or were you working on something that was new to you?

If I had been working on a different book, I’m sure I would have finished that book instead. But I had literally just finished Oh William! The characters were very, very much in my head, and then pandemic began. I realized that I just can’t let these people go. I briefly thought of writing an epilogue to Oh, William! then I thought, no, because I really liked the way the novel ends.

Back then, because nobody knew how long the pandemic was going last, I just started to write scenes. And then as the pandemic continued, I realized, Oh, this is going to be its own book. I never thought I would write about the pandemic. And yet, at the same time, this is a time in history that can’t be avoided, and it should probably be recorded. And if you can do it through Lucy and William, let’s do it.

Do you write from an outline at all?

No, never. And I never write from beginning to end. For years and years, starting back when my daughter was very young, I might only have two hours a day to work—at the most maybe every other day. I learned to write in scene because when I was writing Amy and Isabelle, I began to realize, Oh, I just wasted two hours trying to get Isabel out of the grocery store. Because I didn’t have time, I just jumped into the next thing.

So every time I sat down, I would draw from my own sense of urgency, big or small. There’s always something at any given moment that we are thinking about more than others, so I try and get at that emotion, then transpose it into a character with whatever they are doing. That’s how I learned to write in scenes. I would find scenes with a heartbeat, is how I think of it. The ones that didn’t would get tossed on the floor. But the ones with a heartbeat would sort of arrange themselves, eventually, into a narrative story.

Writing through scenes leads me to think of characters developing through actions and responding accordingly. William is a complicated character who is deeply compassionate and loyal while also deceitful and potentially manipulative. I appreciate the moral complexity of your characters because it presents readers with the challenge to forgive people, and we have the choice to…

…accept them or not, right? The complications of personalities is always what fascinates me. What's one of the funniest things about writing for me is that when I go to the page, I suspend all judgment of them, which is wonderful, because in real life, I'm probably judgmental, because we all are. Honestly, we probably have to be to maneuver our way through the world. But when I when I sit down to write these characters, I love them with the heart of God because I'm just there to report on them, and what they do is just what they do. To not judge them is wonderful for me.

You Might Also Like