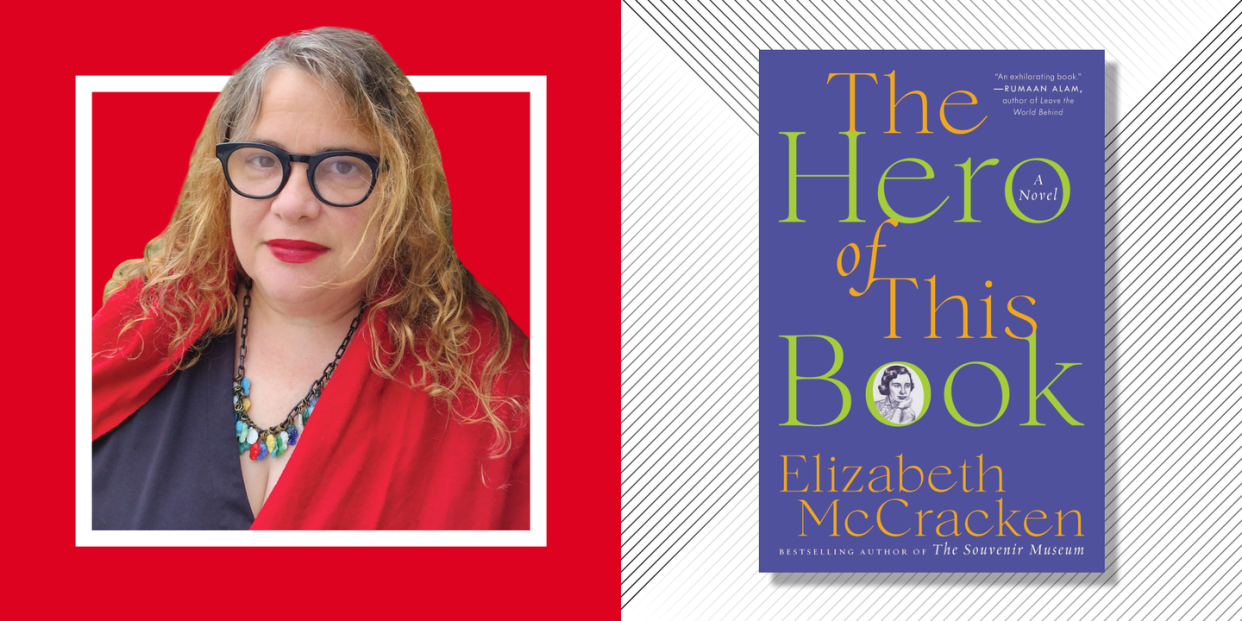

Elizabeth McCracken’s “The Hero of This Book” Is a Loving Ode to Grief and Memory

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

What a time to be alive and reading, when some of our keenest and most eloquent observers of the human heart are reaching the age when their parents die and therefore can—must?—be written about. Is that morbid? Not at all. No writer can fully tell a parent’s story while that parent walks the earth, not least because death completes the tale. Death casts a parent’s life in a new light even as it frees the writer to write. The results can be breathtaking: Margaret Renkl’s Late Migrations, Ann Patchett’s “Three Fathers” and now Elizabeth McCracken’s The Hero of This Book, a boon companion if ever there was one for the great reckoning you can’t avoid except by beating your parents to the grave.

Renkl’s book (a beautiful accretion of poetic prose musings) and Patchett’s clear-eyed yet deeply felt essay (from her 2021 collection, These Precious Days) are autobiographical. McCracken’s book feels autobiographical and reads like memoir (a genre with which she’s poignantly conversant; An Exact Replica of a Figment of My Imagination chronicles the loss of her first child, who was stillborn)—yet the new book’s cover says “A Novel,” and the narrator, a writer, insists that it is one. Some reviewers will doubtless catalog the similarities between the narrator’s life and McCracken’s, and readers may interrupt themselves to google, but really, who cares? Some stories are short, others are longer, McCracken has published both, and this is one of the latter. Fiction or non-, the point is the story’s emotional truth.

The book is set in August 2019, when, ten months after her mother’s death, the narrator goes to London for two nights, “trying to decide what I thought about my life”—London being where, three years earlier, she and her mother roundly enjoyed a museum- and theatre- and libations-filled jaunt together; now the motherless daughter walks around lapping at the places they went. (“I wasn’t moving in our footsteps…but I wasn’t avoiding them.”) The chapters attempt to alternate between the now of London and the many thens and theres of the narrator’s family history and her history as a writer, but her attention proves as fluid as The Thames, with even the present-day sections continually turning back to the past. It may not sound like much to hang a book on—in lesser hands you might call it a walkin’-and-thinkin’ story, and not in a nice way—but in fact there is action aplenty, with all roads (and black cabs and ferries and large cantilevered observation wheels) leading to mother.

“All mothers are unknowable,” the narrator says. Well, yes and no. Her mother was a twin, very short (and proud of it), highly educated, well-employed at Boston University, and her house—meaning the family’s house (the narrator had a father, too: “I miss him. I’m sorry he doesn’t fit in this book”)—was unclean and overflowing to crime-scene levels (though this isn’t a hoarding story). She had a physical disability from birth (in both senses: since birth, and because of it; her own mother, the narrator’s grandmother, referred to it as “a birth injury or a forceps injury”). She walked with two canes for many years, then with a walker, and at the end of her life also used an electric scooter. The book is full of her physicality. Given that it’s also concerned with the nature of writing, you might say the mother’s body was plot and her response to it, character.

About that character: She was abounding in enthusiasms, “a great appreciator,” an eager beholder of life’s rich pageant. She loved the world and herself. She loved restaurants and food. “She loved the singer Tiny Tim, whom she recognized as one of her people: joyful and oddball.” She so loved her own name—Natalie—that she gave gifts to children who happened to share it. And though the narrator says she never said so, she loved her daughter.

As mothers go, she was opinionated but not controlling. “She didn’t (as Mrs. Darling does in Peter Pan) go into my mind to tidy things up, to hide the bad thoughts and plump up the good.” But she lives in her daughter’s head nonetheless. The narrator calls tennis shoes sneakers because that’s what her mother called them. She disdains bedroom slippers because her mother did. When her mother fell down the stairs, she felt the ringing in her own head. “Of course I have a name,” she says at one point. “My mother gave it to me…”

One thing her mother didn’t like? Memoirs, especially memoirs about parents. And so the narrator (although of course she’s writing a novel) worries: about violating her mother’s privacy, about getting her right, even about referring to her only as “my mother, as though that were her most important identity.” But her mother loved a story about herself—and well knew the rules of storytelling where mothers are concerned.

To wit: Twenty pages from the end of the book, we finally learn the truth of her disability, and it’s a shock. Not the medical fact of it, but that it comes so late in the story, as it came so late to the narrator’s knowledge. She was 26 when the truth was revealed (to reveal it here would be a spoiler too far); it had to wait until her mother’s mother died, because the words would have hurt her. “Now my grandmother was dead and my mother could describe herself any way she liked.” And not just herself. In describing the grandmother’s death, the mother can’t stop mentioning that the fatal heart attack caught her with her pants literally down.

The narrator never portrays her own mother in such a compromised position. Or does she? The story concludes with a last internal debate about its own possible crimes—but not before a final litany of the mother’s habits, abilities and traits, a glorious biographical inventory at the end of which, deeply moved, one might have to turn aside and weep. Whoever is doing the writing—fictional narrator or real-life daughter—it’s such a close and loving description that you know she’d rather have the mother than the book.

————

Deborah Way is the creator of the Instagram-based memoir project @thekeepthings, stories of the things people keep to remember lost loved ones. www.thekeepthings.com

You Might Also Like