Elizabeth Lesser on Why We Need More Statues of Women Doing Everyday Things

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

From the book CASSANDRA SPEAKS by Elizabeth Lesser. Copyright © 2020 by Elizabeth Lesser. Published on September 15, 2020 by Harper Wave, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Reprinted by permission.

Recently, I spent the night at a friend’s house in New York City, and I got up early the next morning so I could walk through Central Park to a meeting in Midtown. I entered the park at Fifth Avenue and Sixty-Seventh Street and immediately came upon a large bronze statue. I had passed by this statue many times before, but I’d never stopped to examine it. It was a fine fall day, and I wasn’t in a hurry, so this time I stopped and came close and read the inscription on the base of the monument: “Seventh Regiment New York, One Hundred and Seventh United States Infantry, in memoriam, 1917– 1918.” World War I. A war memorial. Seven larger-than-life soldiers, young men with their helmets, holding bayonets, one soldier carrying a dying, bloodied brother in his arms.

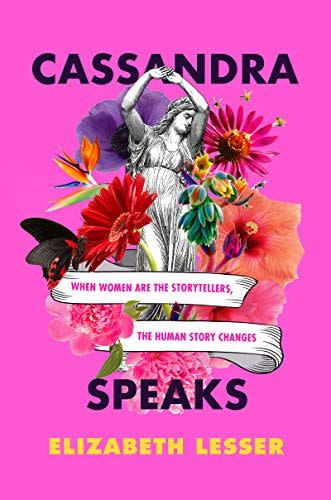

Cassandra Speaks: When Women Are the Storytellers, the Human Story Changes

amazon.com

$15.59

amazon.comAs I stood in front of the statue, I took in the whole scene: the autumn trees, the women and men rushing to work, the nannies pushing strollers, the traffic whirring and honking in the street. I thought how interesting, how strange, that humanity singles out war as the one form of boldness to memorialize. I kept walking, and before long I got to Grand Army Plaza, the gateway to the park at Fifty-Ninth Street. There, rising tall above the crowd of pedestrians, was a statue of the Civil War Union general William Sherman, perched high on a horse, being led by an angel. Sherman is a somewhat polarizing historic figure. He is known for liberating the South from the Confederate Army, and he is also credited with the mass destruction of Atlanta during his notorious March to the Sea, as well as other scorched-earth tactics in the Civil War. He used that same military philosophy as commanding general of the Indian Wars. His policies included the first establishment of reservations, the killing of those who resisted relocation, and the starvation of remaining free-roaming Plains Indians by the mass eradication of buffalo herds.

Again, I stopped to behold this statue; it’s hard not to pay attention to it. General Sherman, and his horse, and the angel, are covered completely in twenty-four-carat gold leaf. It’s a gorgeous piece of art, created by the famous American sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens. I sat on a bench, studied the statue, and wondered, Why, of all the people in the world, does General Sherman get to sit on a gilded horse forever in Central Park? And why is this the same all around the world?

It doesn’t matter where you are—in Paris passing the Arc de Triumph; in Volgograd, Russia, beholding the massive war statue The Motherland Calls; in Cambodia, in the temple ruins, where mile-long walls depict religious battles; or on the Mall in our nation’s capital. Wherever you are on this planet, it seems to have been decided long ago that history would be annotated by the warriors, and that courage, boldness, and strength would be associated with a willingness to fight and die—to put your life on the line for your ethnicity or religion or country.

I used to wonder about this as a kid. Why in school did we have to memorize the dates of a long list of battles and wars, or the names of the men who invented the atom bomb, but not the names of the people who invented things like washing machines, or solar panels, or birth control pills? Certainly, these discoveries (which, by the way, all involved women inventors and investors) also changed the course of history. Who chose violent conflict as the one human activity to laud over all others? Later on, when I was in college, getting my degree in education and doing my practice teaching in an inner-city school, I wondered, What if, alongside the marble tombs for the un-known soldiers, there were also monuments to the countless unheralded teachers who educate our children, keep them safe, prepare them as best they can to be good citizens?

When I became a midwife and witnessed the courage of laboring women, I wondered, What if, next to a statue of a warrior holding his bloody comrade, sculptors had also been commissioned across the ages to represent a woman delivering a baby—strong and noble and, yes, bloody. Does that sound preposterous, gory, gross? Why? Blood is blood, whether it is spilled on the battlefield, as a young person dies, or in the delivery room, as new life is born. Now, I’m a realist—I know that human behavior can become so twisted that if allowed to reach a boiling point some kind of force is required to stop it. But that does not mean we should celebrate violent force as the penultimate definition of being bold, of being heroic. What happens to human consciousness when we memorize the dates of battles, and we pass the war memorials, and sing anthems with lyrics laced with bombs bursting in air?

José Ortega y Gassett, the nineteenth-century Spanish philosopher, said, “Tell me to what you pay attention, and I will tell you who you are.” We have paid a lot of attention to vi- olence and warriors. Search online for “the top ten events in American history.” I did this. On the first site, all ten events were wars or attacks or assassinations. Same with the second list. The third list had the Apollo flight to the moon, plus nine violent incidents. Really? These are the events we want to know ourselves by? Tell me to what you pay attention, and I will tell you who you are. Tell me what would happen to us as a culture if a statue of Rosa Parks were placed right next to the Lincoln Memorial—and Miss Parks was as big and bold as the commander-in-chief? Or if next to the Vietnam War Memorial there was a similar wall with thousands of names of the people who have honed other ways of dealing with conflict—like maybe communicating, forgiving, mediating? Working for justice so that the economic and social conditions that spawn unrest are transformed before they explode? How about monuments to the pioneers in mental health who are helping people heal internal wounds before they inflict external wounds on others?

Tell me to what you pay attention and I will tell you who you are. Are we not also people who create shelters for those battered at home so their kids don’t re-create the cycle of violence? Are we not also the caretakers of our culture—the nannies and home health aides and hospice workers; the farmers and earth stewards; the everyday citizens who feed and house and give jobs and hope to others?

There are twenty-nine sculptures in Central Park and not one honors historical women. A few feature female angels or dancing girls, and there’s one of Alice in Wonderland and one of Mother Goose. Not that I have anything against angels, dancing girls, and fictional characters. But I was happy to learn that an organization called Monumental Women launched a campaign in 2014 to construct Central Park’s first monument representing real women. Because of their persistence, the New York City Public Design Commission finally approved a statue honoring Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Sojourner Truth. The monument will be the first in Central Park’s 166-year history to depict real-life women and will celebrate the largest nonviolent revolution in our nation’s history—the movement for women’s right to vote. Won’t it be great for little girls and boys to walk through the park and see those images and ask their parents, “Who are those ladies? What did they do? How did they do it?” Tell me to what you pay attention, and I will tell you who you are.

In December 2012, just weeks after the massacre at the Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, I was invited to speak at a forum for townspeople who were drowning in shock and grief. A parent whose children attended the school had read my book Broken Open. She thought the message in the book might be a balm for the people of Newtown—the message that if we stay open during difficult times, as opposed to becoming hardened and bitter, we might stay afloat, we might find healing, and eventually we might find our way to a new shore, a new life. We might even use the pain for inner growth and for the betterment of our hurting world. I told the parent who invited me that it was probably still too early for those suffering such severe trauma and loss to consider anything but how to sleep at night, how to take one painful step after the other, how to breathe. Still, she wanted me to come, and so I accepted the invitation.

Since then, I have stayed in touch with many of those Newtown parents and friends. I have watched with great admiration as they have chosen, over and over, to keep their hearts open, and not only to find their way to a new normal, but also to use the pain to fuel something good. To honor their children even as they mourn them every day. Recently, I went back to Newtown to speak again, at the invitation of two of the parents who founded a research and activism organization in their daughter’s name—the Avielle Foundation.

Avielle was only six when the gunman took her life. I am calling him the “gunman” because I do not want to memorialize his name by mentioning it here. I never wanted to know his name. He left a trail of trauma and sorrow in his wake. His violence continues to ripple out. Just weeks after my last visit to Newtown I learned that Avielle’s father had taken his own life, once again proving how violence begets more violence, and the cycle continues.

How do we break that cycle? One way is to change what we pay attention to—what deeds we honor and what names we know. There are many worthy names of people who meet adversity with love and optimism that never make it to the news. Instead, we are bombarded with the names of those who do harm. I am a news junkie. I read and watch and listen to the steady stream of negative stories every day. I feel it is my responsibility to stay informed. Throughout the ages, uninformed, head-in-the-clouds citizens have allowed motivated despots and hate mongers to rain travesties down on their communities and nations. An informed populace is the bedrock of democracy. But . . .

If all we do is immerse ourselves in the stories of bad people doing bad things to each other and the planet, we will sink under the weight of a lopsided story. We will feel alone and outnumbered, when really, there are so many doing wildly imaginative, kind, and brave things at this very moment. This is why I try to eat a balanced news meal every day. You may have to search for the hopeful stories, but they are hiding in plain sight. Once you find them, you’ll be so nourished you will want more, and you will want to share those stories, and even get involved. You will have less time for the nasty stories, the mean-spirited ones, the destructive ones. You’ll want a creativity diet, a hope diet, a wisdom diet. You will not want to fill your mind with violent television shows and movies that are really glorified shoot-’em-up video games. You will get tired of superheroes that continue to meet violence with more violence. You will want to know the names of a different kind of superhero.

You will want to know her name: Antoinette Tuff. Do you know it? You should. She was the bookkeeper at an Atlanta elementary school who prevented another massive school shooting from happening. How did she do this? Not by being armed, not by threatening more violence. Rather, by staying in a small room and calmly communicating with a deranged twenty-year-old gunman, even though she had many opportunities to escape. For more than an hour she spoke to him from her heart, persuading him from using his loaded AK-47- style rifle on the hundreds of children right outside the room. “Don’t feel bad, baby,” she said, according to the tape of her 911 call. “We all suffer. My husband just left me after thirty-three years,” she told the troubled young man. “I got a son with multiple disabilities. If I can get over tough times, so can you.”

Later, when asked how she had done what she did, Ms. Tuff said she practiced what her pastor called anchoring. First anchoring in one’s inner strength, and then letting empathy and compassion lead the way. “I just let him know he wasn’t alone,” she said. “I kept saying, baby, we don’t want you to die today. You belong to us. Just put your guns down. I won’t let anyone hurt you.” And that’s exactly what happened. He put the guns down, and Antoinette guided the SWAT team to come in gently and take him away. Anchored strength in service of compassion averted a national tragedy. But whereas stories that end in violence remain in the news for years, the very kind of action that worked—and could be funded and taught—was presented in the media as a sweet story and then lost after a few days. Antoinette Tuff. Anchored in strength and compassion. Know her name.

Malala Yousafzai. You may know her name already, but it’s a name to keep on the tip of your tongue. She’s the girl who was shot in the head by the Taliban because of her persistence in going to school and encouraging other girls in Pakistan. At a speech at the UN, on her sixteenth birthday, Malala spoke of love and education as the only remedies for hate and violence. She ended her remarkable speech by saying: “The Taliban shot me through my forehead. They shot my friends, too. They thought the bullets would silence us, but they failed. Out of the silence came thousands of voices. The terrorists thought they would change my aims and stop my ambitions. But nothing changed in my life except this: weakness, fear, and hopelessness died. Strength, power, and courage were born.” Malala. Anchored in strength and compassion. Aware of a different kind of power. Know her name. Every time someone trots out a news story featuring the well-known name of a killer, or a criminal, or an elected official doing daily harm, say Malala’s name. Tell her story.

Tammy Duckworth. There are so many reasons to know her name and to tell her story. She is a Purple Heart veteran who lost both of her legs in the Iraq War when her helicopter was struck by a rocket-propelled grenade in the autumn of 2004. She was the first disabled woman ever to be elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, the second female Asian American to be elected to the Senate, and the first female senator to give birth while holding office. Of that first, she said, “It’s about damn time. I can’t believe it took until 2018. It says something about the inequality of representation that exists in our country.” From her hospital bed after giving birth, she began to advocate for expanded parental leave benefits, writing that “parenthood isn’t just a women’s issue, it’s an economic issue and one that affects all parents—men and women alike. As tough as juggling the demands of motherhood and being a Senator can be, I’m hardly alone or unique as a working parent, and my children only make me more committed to doing my job and standing up for hardworking families everywhere.”

Ten days later she rolled her wheelchair into the U.S. Senate chamber to cast a vote, newborn baby in her lap. The Senate had, only the night before, voted unanimously to change the admission standards and allow Senator Duckworth to bring her child to work. That’s my favorite reason to know Tammy Duckworth’s name: she was the first woman or man to vote on the chamber floor holding her baby. Fearless in confronting archaic rules that diminish women’s power, Duckworth was instrumental in changing the admission standards, allowing her and all mothers and fathers who also happen to be senators to bring their babies with them so as not to miss important votes. Similarly, she introduced the Friendly Airports for Mothers Act that compels large airports to include lactation areas for traveling mothers. She is committed to changing the story about motherhood, fatherhood, and work.

When I saw the image of Senator Duckworth wheeling herself onto the Senate floor, I was brought to tears. That image told a new story. A disabled, Asian American, nursing mother, who was just doing her job, and doing it passionately, excellently, vocally, and proudly.

Tell me to what you pay attention, and I will tell you who you are. I search the news, and I search my town and workplace, for names to pay attention to so that we might change the story of who we are. I want to know the names of people anchored in strength and compassion. “I’ve never been interested in evil,” Toni Morrison said, “but stunned by the attention given to its every whisper.” It’s up to us to deny evil the attention it seeks. It’s up to us to demand stories of love and justice, to read and watch them, to validate and elevate them. To pay attention to the women and men who are doing power differently, and to know their names.

Elizabeth Lesser is the author of Cassandra Speaks: When Women Are the Storytellers, The Human Story Changes as well as the bestselling Broken Open: How Difficult Times Can Help Us Grow and Marrow: Love, Loss & What Matters Most. She is the cofounder of Omega Institute, has given two popular TED talks, and is a member of Oprah Winfrey’s Super Soul 100.

You Might Also Like