This Egyptian Desert Oasis Is a Destination Most Travelers Skip — and That's Exactly Why You Should Go

In Egypt’s Western Desert, the ancient oasis of Siwa is home to one of the world’s most extraordinary hotels.

Manuel Obadia-Wills

Adrère Amellal, a hotel in Siwa, Egypt.From the plane, I looked down on a patchwork of emerald palm groves, rows of silver olive trees, and vast salt-ringed lakes that seemed to glow in psychedelic shades of cerulean and aquamarine. Surrounding these pockets of lushness was an ocean of sand, and the combination filled me with a sense of isolation that was almost overwhelming.

I was about to land in Siwa, an oasis in Egypt that includes a town of 20,000 people, a few historically significant sites, and a handful of small hotels. It lies about 350 miles west of Cairo as the crow flies, and 30 miles east of the Libyan border.

My journey had been more than 20 years in the making, sparked by a conversation with Peter Beard, the legendary photographer, artist, and writer. He had told me that one of his favorite hotels was a place called Adrère Amellal, which resembled a fortress made of sand in Egypt’s Western Desert.

Manuel Obadia-Wills

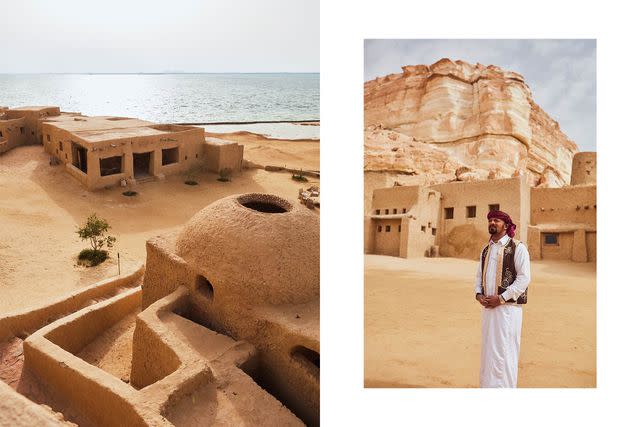

From left: The buildings of Adrère Amellal, which sit beside Siwa Lake, are made of a mixture of salt and clay; the hotel’s manager, Mohamed Gegal, with White Mountain in the background.The hotel was in Siwa, a place that, he explained, was part of Egypt but had the feeling of an independent state: for millennia, generations of Berber tribes had lived there under their own laws. The heart of ancient Siwa was Shali (now also known as the Old Town), a fortified village built in the 13th century to protect the community from attacks by neighboring tribes.

In 1926, a series of massive rainstorms destroyed many of Shali’s buildings, which were made kershef, a mixture of salt and clay. And while some of those structures still stand, the residents of modern Siwa — the majority of whom are descendants of the Berbers — live nearby in homes made of stone. The streets buzz with motorbikes and vendors selling falafel and fresh aish baladi, the ubiquitous traditional flatbread.

From a distance, the buildings appeared to emerge organically from the sand, and then later to disappear into the nearby cliffs of the giant, table-topped White Mountain, which towers over the hotel.

The Old Town, meanwhile, resembles an archaeological relic, although it is slowly being restored by private citizens. One of them is Adrère Amellal’s creator, Mounir Neamatalla. A Cairo native who holds a Ph.D. from Columbia University, he founded Environmental Quality International (EQI), a consulting company that is the driving force behind some of the country’s most significant preservation projects. Neamatalla and I shared a common friend in Louis Barthélemy, a French artist, who lives part-time in Cairo. He caught wind of my fascination with Siwa last year and offered an introduction— and the impetus to finally make a trip.

A quick phone call was all it took to garner an invitation from Neamatalla to join him at Adrère Amellal over Easter weekend. There are no regularly scheduled commercial flights to Siwa, so I joined a charter, which brought us from Cairo International to Siwa’s tiny military airport in 90 minutes. (Going by car from the capital takes 12 hours along the coast on bumpy, mostly empty roads. Drivers often break up the long journey with a stop in the resort town of Matruh, which sits on the Mediterranean Sea. Aside from the glorious white-sand beaches, history buffs can examine several World War II shipwrecks along the coast.)

Manuel Obadia-Wills

From left: A guest dips her toes in the salty waters of the lake; thick walls shield guest rooms from the desert heat.After more than two decades of anticipation, arriving at Adrère Amellal felt almost surreal. From a distance, the buildings appeared to emerge organically from the sand, and then later to disappear into the nearby cliffs of the giant, table-topped White Mountain, which towers over the hotel.

My room, which overlooked a lake and a grid of organic vegetable beds, was simply furnished, with a packed-earth floor covered in handwoven rugs, a comfortable king-size bed, and a fireplace. Most of the furniture was made with palm fronds, and thoughtfully placed windows allowed the circulation of even the faintest breeze — an important detail in a place where daytime temperatures in the summer can reach 100 degrees. There is no air-conditioning or electricity; at night, guests make their way by the light of candles and lanterns. A massive spring-fed pool was perfect for taking a cooling dip.

Related: This New Luxury Nile River Cruise Is a Gateway to Egypt's Ancient Wonders

Over mint tea in one of the hotel’s lounges, Neamatalla — casually but impeccably dressed in a linen shirt and pants, with a safari hat to shield himself from the Egyptian glare — explained how he came to Siwa.

In 1996, Neamatalla was 50 years old and at a crossroads in his career. EQI was up and running, and he had been working for decades with the government to create a more sustainable waste system for Cairo. When an anthropologist colleague suggested he visit Siwa and explore its ruins, Neamatalla readily agreed.

Manuel Obadia-Wills

From left: Off-roading on desert dunes, a popular excursion in Siwa; Adrère Amellal’s spring-fed pool.“We arrived after twelve hours of driving, and the sun was about to go down,” he said. “I remember lifting my eyes and seeing White Mountain, and directly in front of me the fortress of Shali. I immediately recognized that my fate was tied to these two places.” The seemingly mystical pull that Siwa had on Neamatalla led to the idea for Adrère Amellal, which means “White Mountain” in the local Berber dialect. The purpose was to create a sanctuary, a place where his friends and acquaintances could get away from modern life in the vastness of the desert.

More Trip Ideas: Morocco Is a Perfect Family Adventure — With Desert Camps, Motorcycle Rides, and Camel Rides

Construction of the complex, which took nearly four years, was guided by its relation to the mountain. “Every morning I would look at the volume of the proposed architecture, and if I felt something was intruding on the mountain I would take it away,” he said. Neamatalla gives much credit to his longtime collaborator and cousin, the Iranian-Egyptian architect and designer India Mahdavi. “The creation of Adrère Amellal was possibly the freest way of building there is,” Mahdavi told me from her office in Paris. “Construction took place without blueprints. We made traces on the soil before mud and salt blocks were piled up to raise an edifice that is in consonance with its environment.”

Manuel Obadia-Wills

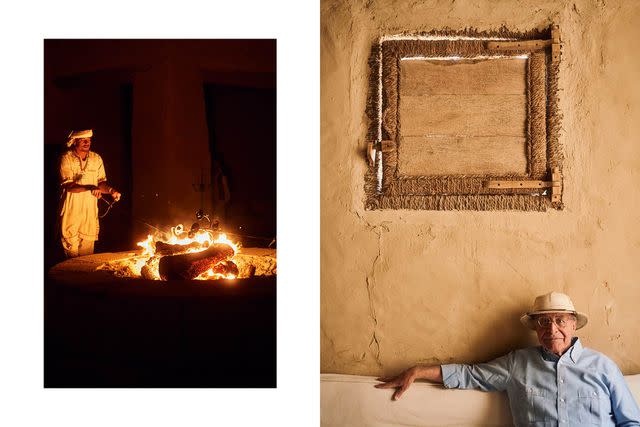

Adrère Amellal, in Siwa, Egypt, as seen from neighboring White Mountain.At dusk on my first night, I followed a winding path of flickering lanterns to a firepit where drinks were being served. A couple of gin and tonics later, guests were led to a series of tables set for eight people. (“Eight is the ideal number for unified conversation,” Neamatalla told me.) I would find out that dinner locations change every night, but are often outdoors, under the stars. Instead of printed menus, a three-course meal of vegetable-dominated, Mediterranean-inspired dishes would appear, served on vintage silver platters. All of the organic produce and herbs used are grown on site. My favorites included hibiscus risotto and zahret koussa — zucchini flowers stuffed with vegetables and fragrant herbs — along with a delicate date soufflé.

The hotel offers more activities than I could fit into my three-day stay: hikes up White Mountain, desert 4 x 4 drives; dips in salt lakes; and excursions to extraordinary historic sites like the Temple of the Oracle of Amun, where Alexander the Great paid homage in 331 B.C. Surprisingly, I found that I didn’t miss electricity or Wi-Fi at all, and in the evening, their absence not only seemed to heighten my senses but also allowed for a profound sense of peace amid the desert landscape. In a post-pandemic world, I thought, this is really what everyone is searching for — a place to disconnect and reconnect.

The hotel offers more activities than I could fit into my three-day stay: hikes up White Mountain, desert 4 x 4 drives; dips in salt lakes; and excursions to extraordinary historic sites.

Part of that connection is creative collaboration. For the past two decades, Neamatalla; his sister, Laila Neamatalla, a jewelry designer who champions Egyptian craft; and Mahdavi have commissioned work from locals like the salt-carving artisan Sayed Aboul Qassem Omar and master embroiderer Faiza Soliman Abdel Salam. Their work is sold both at the hotel and in Cairo’s top design showrooms, thanks to Laila’s connections. Barthélemy also collaborated with Siwa craftswomen on a fashion line, Udjat, that is now sold at the property.

On my final morning, I drove the half-hour from Adrère Amellal to Old Town to see the fruits of EQI’s long-standing project, the Siwa Sustainable Development Initiative. It encompasses several building renovations, where locals are trained in kershef building techniques. I was met by crumbling façades reminiscent of jagged teeth, like a sandy-hued Dalí painting come to life. Amid the ruins, the three dozen fully restored buildings stood triumphant. These included two ancient mosques and a space that is used as a health clinic.

Manuel Obadia-Wills

From left: A staff member preparing candlesticks—an important resource at this electricity-free hotel; Mounir Neamatalla, founder of the hotel.Neamatalla has also partnered with Egypt’s Ministry of Tourism & Antiquities to create a pioneering museum. The Siwa Fine Art Museum’s master plan is to exhibit a collection of artifacts from Siwa in a labyrinth of former dwellings, with each room dedicated to a single object. It is set to open in 2025.

“An oasis like Siwa is a design laboratory where we learn, on a micro scale, the results of sensitive interventions,” Neamatalla told me on my last night over shish kebabs and pumpkin couscous. In a place that’s defined by the ancient, it felt as if Siwa was also a harbinger of what thoughtful stewardship could mean for the future.

Where to Stay

Adrère Amellal: The vision of Mounir Neamatalla, this 39-room hotel is a compound of nine structures, all built by hand, with a spring-fed swimming pool. There is no electricity or Wi-Fi, so guests are able to fully connect with the desert surroundings.

What to Do

Shali Fortress: This historic village, founded by Berbers in the 13th century, offers a glimpse of Siwa’s ancient life.

Temple of the Oracle of Amun: The ruins of this religious structure dedicated to Amun — one of the most widely worshipped deities in the ancient world — was a pilgrimage site of Alexander the Great.

How to Book

T+L A-List travel advisor Chris Bazos (chris@ travelous.com; 888-495-5925) can arrange all the logistics for a Siwa trip, including a charter flight from Cairo.

A version of this story first appeared in the April 2023 issue of Travel + Leisure under the headline "Sand Castles"

For more Travel & Leisure news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on Travel & Leisure.