'The Ed Sullivan Show' Turns 75! Looking Back on the Show's Legacy

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Ed Sullivan was 46 years old and a relative unknown when, on June 20, 1948, the CBS television network introduced him as the host and co-producer of a new Sunday night variety program called the Toast of the Town. Leaning heavily on the show-business connections he’d cultivated over the years as a New York-based newspaper columnist, Sullivan’s lineup that evening included the then-breaking-big nightclub comedy team of Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis, Broadway giants Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein, a ballet dancer, a classical pianist, an interview with a boxing referee, and, for local color, a Bronx fireman who’d won a community singing contest.

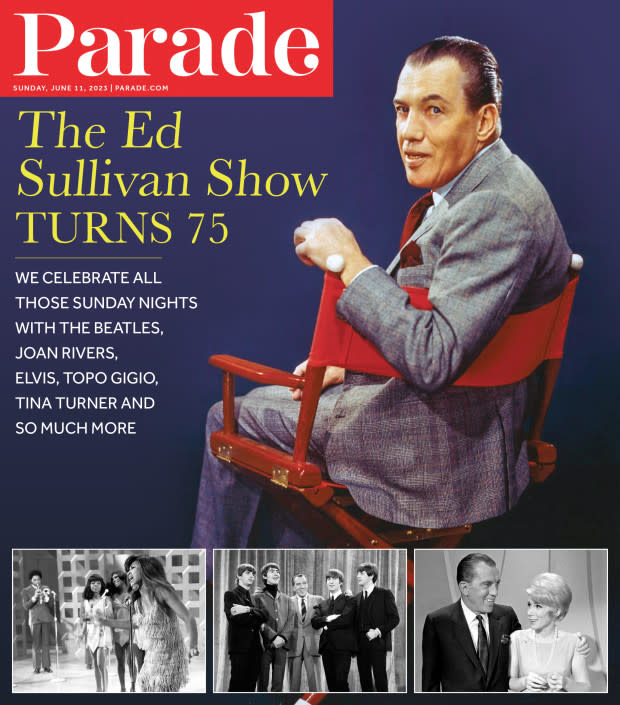

COVER PHOTOGRAPHY COURTESY THE ED SULLIVAN SHOW; INSETS: CBS/GETTY IMAGES (2)

On paper, the mix made little sense. Yet, from that night on, as Ed Sullivan continued to present his hand-picked but seemingly random assortment of performers—and notably continued to fumble his way through between-act segues and commercial announcements—the program began to attract a steady following.

Sullivan’s Toast of the Town was, by the end of 1948, one of early TV’s highest-rated programs. At the time, there were fewer than half a million TV sets in operation, mostly in neighborhood bars and taverns. Over the next few years, as sets came down in price and began taking their places in living rooms across the country, Sullivan solidified his position as one of the nation’s premier showmen.

It was a perch he would go on to occupy for more than two decades.

A Cultural Gatekeeper

At the height of his popularity in the late 1950s and ’60s, Ed Sullivan’s program averaged an estimated viewership of well over 40 million. It was a testament to his unfailing knack for assessing, on a weekly basis, the entire width and breadth of the entertainment galaxy—highbrow, lowbrow, and everything in between. He then chaperoned its best and/or brightest to a general audience whose overall tastes he understood, and ultimately helped shape.

In so doing, Sullivan served as perhaps the most important cultural gatekeeper for multiple generations of Americans. He brought viewers showcase performances by acts ranging from the Bolshoi Ballet to Johnny Puleo and His Harmonica Gang; Sam Levenson to Señor Wences; Richard Burton to Richard Pryor; Mahalia Jackson to The Jackson 5. And, of course, from Elvis Presley to The Beatles. To paraphrase Frank Sinatra’s “New York, New York,” for just about any entertainer on the planet, if you could make it there—on The Ed Sullivan Show— you could make it anywhere.

By any imaginable standard, Sullivan was easily the most unlikely “star” in the history of television. He was a master of ceremonies whose presence on his own show was so devoid of showbiz pizzazz and personal charisma that he was often referred to as, simply, “Old Stone Face.” And yet, for one hour every Sunday night for nearly a quarter of a century, Sullivan was welcomed into living rooms across America with a loyalty that remains unequaled since his show went off the air in 1971.

How did he do it? Sullivan once said he followed a simple formula: “Open big, have a good comedy act, put in something for the children—and keep it clean.” That formula was informed by Sullivan’s innate sense of good-willed age-, race- and ethnicity-blind inclusion, a product of his upbringing. Born into a devout Irish-Catholic family in New York’s East Harlem, he was raised in Port Chester, NY, a mostly working-class community. Excelling at sports, he played with and against a diverse group of area athletes, which instilled in him important social values. (“On the field, your name or color or religion cut no ice,” he’d later recall. “You stood or fell on your own performance.”) As he grew up, Sullivan also got his first taste of the allure of show business, watching medicine-show salesmen successfully hawking their wares in Port Chester’s public squares. He attended local vaudeville shows, where he marveled at the talents of comedians, jugglers, acrobats, magicians, comedians, singers, dancers and actors commanding attention from audiences of all ages. It was a blueprint he’d later refine to a near science.

Bitten by the journalism bug while still in high school, Sullivan began writing about sports for his local paper. Not long after graduating he moved to Manhattan, where he spent the Roaring Twenties working his way up the newspaper ladder as a sportswriter for various tabloids. In the process he became a familiar figure not only at sporting events but also as a denizen of New York City nightlife, with Sullivan organizing and emceeing celebrity-packed sports dinners sponsored by his paper. Here, Sullivan rubbed shoulders with sports figures as well as theater, film and radio stars. He was so comfortable around famous people that by 1932 he’d become the Broadway columnist for the Daily News—a post that, even after he became a TV icon, he would hold onto for the rest of his life.

Throughout the 1930s and into the ‘40s, Sullivan was seen alongside those in the public eye nearly every night of the week, and he became adept at putting together and/or hosting all manner of entertainment programs. In 1942, he produced and brought to Broadway an all-African-American revue, Harlem Cavalcade, and after the U.S. entered World War II, he tirelessly organized and emceed benefit shows sponsored by everyone from the Red Cross to the United Jewish Appeal, raising hundreds of thousands of dollars for the war effort.

Must-watch Sunday was born

Television was still a new mass medium in 1948. Intrigued by the job Sullivan had recently done hosting the broadcast of a Daily News-sponsored dance competition, CBS put him on the air with his own show. And once he began to succeed, Sullivan built up his show with innovation and boldness. Recognizing that Broadway theaters were traditionally dark on Sunday nights, he began engaging members of hit productions to perform scenes from their shows. He sometimes staged hour-long tributes to Great White Way icons such as Cole Porter and Helen Hayes. And though the film industry had viewed television as an enemy in its infancy, Sullivan coaxed most of the major studios into letting him present clips from upcoming movies and even getting major stars such as Humphrey Bogart and Marlon Brando to appear on his program. By the end of the 1954-55 season, a new contract with CBS put his salary in the six figures, and in the fall of ’55, just as he was about to grace the cover of Time magazine, the program was retitled, simply, The Ed Sullivan Show. He’d finally made it to the top.

Then, on Sept 9, 1956, came the icing on the cake, spelled E-L-V-I-S.

Elvis Presley had appeared previously on NBC, including one program earlier that summer on Sullivan’s Sunday night competitor Steve Allen’s show. In fact, it was Allen’s beating him in the ratings that week that finally nudged the dubious Sullivan to book Elvis for three appearances at the astronomical price of $50,000. Yet it was Presley’s first performance on the Sullivan show that drew the biggest audience, as an estimated 60 million viewers—a staggering one-third of the country—tuned in. While Presley was already being hailed as the “King of Rock and Roll,” his initial appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show was, for America, the official coronation.

Related: Elvis Presley's Net Worth Is Impressive—See How the Singer Amassed His Fortune

As a result of Elvis’ breakthrough, Sullivan tapped into the teen audience throughout the remainder of the 1950s. He booked performances by virtually all the biggest rock and roll and pop acts, including Buddy Holly, Fats Domino, The Everly Brothers, The Platters, Bo Diddley, Connie Francis, Johnny Mathis and Sam Cooke. While most adults looked upon the coming generation’s music as little more than a trivial passing fad, Sullivan presented his youth-oriented singing acts with simple, nonjudgmental respect. In 1957, after Cooke’s rendition of “You Send Me” was abruptly cut short by CBS when the live show ran late, the network was flooded with angry calls from Cooke’s fans. In response, Sullivan brought him back a month later, apologized to him on air, and then gave him time to perform several songs.

A surprisingly progressive show

As America transitioned into the 1960s, Sullivan broadened his horizons to include keeping the pulse not only on pop culture, but also on the world around him. He took his show international, broadcasting from locations in Europe and Asia. As the Cold War escalated, he even staged shows from the Soviet Union and in front of the Berlin Wall, where Louis Armstrong’s trumpet rang out with “When the Saints Go Marching In.” With folk music and progressivism on the rise, Sullivan’s audience heard The Brothers Four sing Woody Guthrie’s “This Land Is Your Land” and might have seen 21-year-old Bob Dylan perform his satirical “Talkin’ John Birch Society Blues” in 1963 if not for the CBS censors, who heard the song at the show’s dress rehearsal and refused to let him perform it. (Rather than agree to play another tune, Dylan famously packed up his guitar and left, and never did appear on the Sullivan show.)

Alongside Borscht-Belt comics like Myron Cohen and Henny Youngman, Sullivan booked cerebral Mort Sahl, who skewered politicians from both sides of the aisle. Ever the civil rights advocate, Sullivan continued to showcase African American performers such as comedians Moms Mabley, Nipsey Russell, Dick Gregory and Richard Pryor, as well as musicians such as Ray Charles, Nina Simone, Dionne Warwick and James Brown, and Motown artists like Smokey Robinson & the Miracles, The Temptations, The Supremes and the Four Tops. Their collective appearances underscored Sullivan’s leveling-the-playing-field-for-all philosophy.

February 9, 1964, is probably the most famous date in the history of The Ed Sullivan Show, as 73 million Americans tuned in to see The Beatles make their live debut on U.S. soil. In contrast to Presley’s first appearance, here Sullivan led the way, making the decision to book the band after he’d been tipped off by his European talent scout about their phenomenal success abroad. Sullivan had quietly met with Beatles manager Brian Epstein in New York in November of ’63 and contracted the group for three engagements in what turned out to be perhaps the biggest coup of his entire career—$3,500 for each show—including one perk: the Fab Four’s airfare was covered. By the time they landed in New York a few days before their first show, they’d already become stars. Once they completed their high-spirited two-set Sullivan performance, John, Paul, George and Ringo were bona fide superstars.

Just as it had been with ’50s rock and roll following Presley’s debut, the Beatles’ conquering of America opened the doors for the “British Invasion,” and Sullivan soon was welcoming acts such as The Animals, The Searchers, Petula Clark, Dusty Springfield, Lulu, The Dave Clark Five and Herman’s Hermits. The Rolling Stones made several notable appearances as well, though not without some rough patches. Ever the prim, family-conscious host, Sullivan didn’t particularly like what he saw the first time the Stones played his show in October ’64—literally—and told their agent that, while he’d have them back again, he expected them to dress better and also use some shampoo. In January 1967 he let the Stones perform their new hit “Let’s Spend the Night Together,” but only on the condition that they change the lyrics to instead say “Let’s spend some time together.”

Throughout the ’60s, Sullivan continued to feature his vaudeville-based array of acrobats, jugglers, animal acts, magicians and puppets. Even there, he made an important cultural contribution: Most people forget that, well before Sesame Street, Jim Henson’s Muppets were frequent Sullivan guests. Meanwhile, few around at the time could forget the all-too-regular appearances (50 in all) by the little Italian puppet Topo Gigio and his often disarmingly warm conversations with Sullivan. Complete with the tiny rodent’s signature tag line, “Eddie, keeese-a me goodnight,” these skits (many written by up-and-coming comedian Joan Rivers), at last brought out a side of the impresario few viewers knew existed.

Eventually, between the growing generation gap of the 1960s and the emergence of the youth counterculture late in the decade, close-knit family life in much of America began to show signs of unraveling, and Ed Sullivan and his show began to show their age as well. In 1967, after Jim Morrison of The Doors ignored Sullivan’s demand that the group not use the word “higher” in the band’s hit “Light My Fire” and sang it anyway, the edict that they’d never play the Sullivan show again made little impression on the group. As the decade turned, CBS began looking to appeal to a younger, more urban demographic, and in early ‘71, Sullivan was notified that his program was going to be canceled.

The final presentation of a new weekly The Ed Sullivan Show took place on March 28, 1971, and on October 13, 1974—fittingly, on a Sunday night—the great showman passed away at age 73. As evidenced by the billions of views of clips from his programs that have resonated with worldwide audiences over the last 50-plus years since The Ed Sullivan Show ended its initial run, his is a legacy that lives on, unsurpassed in not only television history, but in the entire history of popular culture as well.

The Ed Sullivan Show by the numbers

728 — Seats in the Ed Sullivan theater (the home today for The Late Show With Stephen Colbert)

40 million+ — Average viewership during the show’s peak years

73 million — Viewership of The Beatles episode of the show

$164,000 — Estimated salary for Ed Sullivan in the 1960s.

$1,000 — Fee paid to the stars who would “show up” in the audience for a chat—including heavyweight champ Joe Lewis

1,068 — Number of episodes of the show

$3,500 — What The Beatles were paid per show for their appearances (plus airfare) in 1964

$50,000 — What Elvis was paid for three performances in 1956 and 1957

23 — The number of times Spanish comedian and ventriloquist Señor Wences was on the show

50 — The number of times the famous Italian marionette Topo Gigio appeared on the show. It took six handlers to move Topo’s arms, legs, toes and eyes.

Oct. 31, 1965 — The broadcast date of the first color episode of The Ed Sullivan Show

The Ed Sullivan Show streams for free on Freevee or check out edsullivan.com or The Ed Sullivan Show on YouTube.