These Eco-friendly Hotels in Costa Rica Have Organic Gardens, Beachfront Pools, and National Park Views

The concept of the eco-lodge — now so prevalent around the world — has been perfected in Costa Rica over four decades. Meet the new generation of pioneers taking green tourism to the next level.

Jake Naughton

Sunset on Santa Teresa beach.Sunlight filtered through the treetops as I surrendered my body to the harness. It would soon be time to drop back down to the forest floor, but for now I stayed put, spinning in a slow circle and marveling at the explosion of epiphytes — moss, lichens, and ferns in every shade of green — that surrounded me.

Jake Naughton

The suspension bridge at Savia, a private nature reserve in Monteverde.I was dangling from an enormous tempisque tree at Savia Monteverde, a 17-acre private reserve in the Costa Rican cloud forest. Savia is the latest project by the owners of Hotel Belmar, the oldest continually operated eco-lodge in the town of Monteverde, and my home for the first few nights of a 10-day journey through Costa Rica’s Puntarenas province.

Jake Naughton

The rooms at Lapa Rios Lodge are connected by a wooden boardwalk that winds through the forest.The Belmar family designed Savia as a forest immersion: part ecology lesson, part meditation session, part thrill ride, and a tranquil alternative to the high-speed zip lines that scream through the canopy elsewhere in the region. “When we are in the trees, we are in an environment that is not our own,” said Savia’s cofounder, Andrés Valverde, as he dangled beside me in his own harness. He gestured to the sea of bromeliads that had taken root on the tempisque’s mossy branches. “It is like being in a coral reef.” On another limb we spotted a cluster of micro-orchids with flowers so small they can only be pollinated by a particular species of tiny, metallic-green bee.

Jake Naughton

A private plunge pool at Lapa Rios.As I began my descent, a blue-throated mountain-gem hummingbird darted into the foliage in an iridescent blur. In the distance, sheaves of mist swirled through the treetops. “We use awe as a catalyst for change,” Valverde said. He must have seen the look of wonder on my face. “With 17 acres, I’m not saving the world. But if every person who passes through here feels that connection, I think they will do something for conservation.”

Pura vida. Pure life. The phrase has been part of Costa Rica’s vernacular for decades, as both a greeting and a goodbye. It’s an expression of thanks, a way to say “No problem!” and a reminder to be present and live simply. For Costa Ricans, pura vida is a way of life.

Jake Naughton

From left: The Osa Peninsula, as seen from the air; Edwin Villareal, a guide at Lapa Rios Lodge, leads a hike to a waterfall near the property.This concept partly explains the country’s commitment to conservation. In 1948, it abolished the army, diverting the funds into education, health care, and environmental initiatives. In subsequent years, the country doubled its forest cover; protected more than 25 percent of its land by putting it into reserves, wildlife refuges, and national parks; and amended its constitution to include the right to a healthy environment.

Prioritizing people and nature has made Costa Rica an attractive destination for international travelers. In the 1960s and 70s, those travelers were mostly scientists drawn by the country’s biological riches. But it wasn’t long before word of those riches got out, and by the early 90s, Costa Rica had emerged as a plum vacation spot for nature lovers. Rustic lodges and guide services cropped up — some owned by Costa Ricans (or Ticos, as they call themselves), others by foreigners, laying the groundwork for a new, environmentally conscious style of travel called ecotourism.

Jake Naughton

From left: Oscar Gabriel Morera Vega, who leads Hotel Belmar guests on horseback rides at nearby Finca Madre Tierra; Hotel Belmar, in Monteverde, a town at the edge of the cloud forest.But there was a caveat. Alongside the many businesses that implemented responsible tourism policies were others that rode the ecotourism wave simply by marketing themselves as “green.” In response, the country unveiled its Certification for Sustainable Tourism program in 1997, which set rigorous standards to evaluate a tourism entity’s sustainability practices. These days, many Costa Ricans in the travel industry are implementing creative initiatives that draw upon the lessons of the past while building a more sustainable future.

Surrounded by fruit trees and organic vegetable gardens on the edge of Monteverde’s cloud forest, Hotel Belmar is an oasis within an oasis. My room, lined with honey-colored wood, felt like a tree house, with a huge wraparound terrace and windows that opened to a real-life nature soundtrack. Early each morning a pale-billed woodpecker came rat-a-tatting at my window. Green parakeets produced a cacophony of squawks from the nearby trees.

If Costa Rica has become a global model for sustainable tourism, Monteverde is where that model began. In 1951, a group of Quakers arrived from the U.S. after refusing to register for the peacetime draft. They purchased 3,400 acres of land and divided it into individual homesteads for dairy farming and agriculture. They left the forested mountaintop untouched to protect their watershed, which burbled with springs that spilled into the Río Guacimal.

Jake Naughton

Playa Carmen, near the town of Santa Teresa.The little town quickly emerged as a magnet for biologists who wanted to study the teeming biomass of the cloud forest, particularly the now-extinct golden toad. The scientists shared concerns about the region’s unchecked deforestation with the Quakers, and in 1972 the two groups worked together to establish the Monteverde Cloud Forest Biological Reserve.

I spent a morning with Hotel Belmar’s founder, Vera Zeledón, at Finca Madre Tierra, her farm in the nearby hamlet of Alto Cebadilla. Small in stature but with a firecracker personality, Zeledón drove up in a rugged ATV wearing a baseball cap and muddy red-rubber boots. “When we first came here there was just a little Quaker pensione,” she said. “That’s where I learned how to make bread, granola, and cheese.” In 1985, she and her husband, Pedro Belmar, built their own place — a Tyrolean-style guesthouse inspired by the decade they had spent working in Austria.

These days she spends most of her time at the farm — the first in Costa Rica to receive carbon-neutral certification. She started it with just a few cows and horses, but over the past 15 years it has grown to include coffee production, cheese making, and an extensive composting system. Produce, eggs, and cheese from the farm appear on the menu at Celajes, Belmar’s restaurant; in turn, the hotel’s food scraps fuel both the chickens and the compost heap, while spent barley from Belmar’s new microbrewery goes to the cows.

“Everything moves in circles here,” Zeledón said as we snacked on homemade tortillas with eggs and fresh cheese. “When people come to visit, we spread the seeds of ecological consciousness around the world. That’s our goal.”

"When people come to visit, we spread the seeds of ecological consciousness around the world."

Vera Zeledón, Hotel Belmar

Jake Naughton

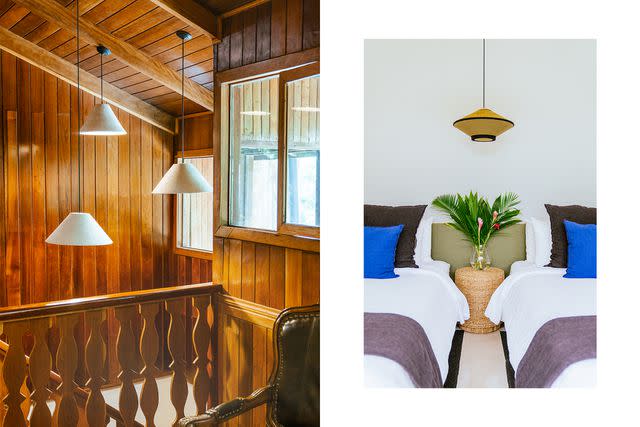

From left: A private plunge pool at Nantipa; wood furnishings and floors in a villa at Lapa Rios, an ecolodge on Costa Rica's Osa Peninsula.In 2004, National Geographic Fellow Dan Buettner identified five places around the world where people live unusually long and healthy lives, dubbing them “blue zones.” The Nicoya Peninsula, on Costa Rica’s northwestern coast, is one of those places.

My next stop was Santa Teresa, a bohemian beach town on Nicoya’s southernmost shore. In the past decade or so the town has blossomed from a quiet fishing village into a haven for the surfers who ride its year-round breaks. Though I didn’t go for the swells, the ocean beckoned. As soon as I found my bungalow at Hotel Nantipa, I laced up my running shoes and headed for the beach. In the water, surfers straddled their boards, eyes on the horizon. On the shore, dogs splashed and chased. I ran until the sky streaked pink and then threw on my bathing suit for a sunset swim. The tide had retreated, revealing a deep pool where I floated on my back and decided that Santa Teresa was a place where I could happily grow old.

“Santa Teresa has something magical to it,” said Harry Hartman over dinner at the hotel’s Manzú restaurant. Born and raised in San José, Costa Rica’s capital, Hartman, who co-owns the hotel with his childhood friend Mario Mikowski, first visited the peninsula when his children were small. Eventually he purchased the wild, oceanfront property where we sat eating patacones — crispy plantain fritters — heaped with refried beans, guacamole, and fresh pico de gallo.

The friends wanted to create a place reminiscent of those free-and-easy days Hartman spent in Santa Teresa with his young family, upping the ante on luxury but not distracting from the area’s natural beauty. Nantipa, which means “blue” in the language of the Indigenous Chorotega people who once inhabited the peninsula, is the realization of that goal. Only six trees were removed during construction, despite permits to cut down 80. Later, Hartman and Mikowski developed robust sustainability standards that extend far beyond eliminating single-use plastics. They now support the efforts of multiple, often underfunded, initiatives that, as Hartman put it, “work with their fingernails.” They have forged relationships to make sure tourism dollars go directly into the pockets of local producers and providers.

Jake Naughton

From left: Passion-fruit cheesecake at Lapa Rios; the Canopy Room at Hotel Belmar.Early the next morning I drove south to Malpaís to meet one of those local providers: Tico fisherman Jason Rodriguez Ugalde, who runs charters off the coast near Cabo Blanco Natural Reserve. In his bright turquoise boat we cruised over calm seas past Isla Cabo Blanco, an important nesting site for Costa Rica’s population of brown boobies. Overhead, the birds swooped and soared.

During high season Ugalde might go out two or three times a day — business that enables him to hire extra crew. On off days, he fishes with his wife. There’s never a shortage of fresh fish for his family, he told me. To prove his point, we spent the next couple of hours reeling in one fat yellowfin after another, until my arms began to ache from the effort.

That afternoon I walked through Santa Teresa, passing funky boutiques, surf shops, and hip, California-style juice bars. At a little family-owned restaurant called Soda Tiquicia, I met Camila Aguilar, Nantipa’s concierge, for lunch. Afterward we climbed into the hotel’s utility vehicle and joined the parade of ATVs and motorbikes bumping through the potholes on the town’s unpaved main drag.

About eight miles up the coast, we arrived at the Caletas-Arío National Wildlife Reserve, where a stretch of shoreline is an important nesting site for endangered sea turtles. Between June and December, hundreds lay their eggs on the beach. “Only one will survive out of a thousand,” said Keylin Torres Peraza, a project coordinator at the Center of Investigation for Natural & Social Resources (cirenas), the organization that oversees the reserve. cirenas began its sea-turtle conservation program in 2018, enclosing a large, sandy area above the high-tide line in driftwood and mesh. Inside, roughly 200 nests contained eggs rescued from poachers and predators by staff and volunteers during their nightly patrols.

Jake Naughton

From left: Inside the top-floor Canopy Room at Hotel Belmar; a beachfront villa bedroom at Hotel Nantipa.At Peraza’s feet sat a bucket filled with wriggling olive ridley turtles that had emerged from their eggs just a few hours earlier. Peraza tipped the bucket on its side. The hatchlings tumbled out and began their pilgrimage to the sea. Their progress, tentative at first, quickly grew purposeful, tiny flippers propelling them forward until, one by one, they disappeared into the surf.

In late December, just six weeks after my visit, an arson attack destroyed the hatchery. “Some people feel territorial about this beach,” Peraza told me over the phone. “They don’t like what we’re doing.” To soothe the friction, cirenas works with local schools, offering lessons in conservation and inviting the students and their families to join them on the beach for turtle releases. But with limited staff and resources, they can’t do as much of that as they’d like. For now, rebuilding the hatchery and increasing awareness about their work is the priority — efforts Nantipa helps to fund.

Whenever I told people in Costa Rica that I was headed to the Osa Peninsula, their reaction was always the same: “You are so lucky!” A holy grail for nature lovers, remote Osa is home to 2.5 percent of the earth’s biodiversity, while covering less than a thousandth of a percent of its surface. Intact primary forest makes up the majority of the landscape, an untamed wilderness that provides habitat for tapirs, jaguars, ocelots, giant anteaters, two-toed and three-toed sloths, and the largest population of endangered scarlet macaws in Central America. Separating the peninsula from the mainland is Golfo Dulce, one of just four tropical fjords in the world, where Pacific humpbacks come to breed and birth their young.

Jake Naughton

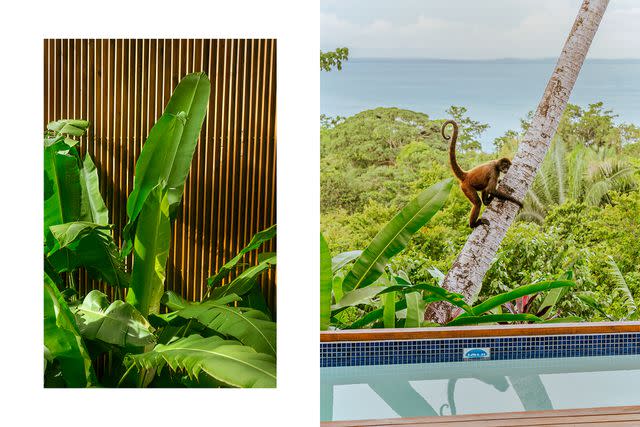

From left: Banana plants at Lapa Rios Lodge; a monkey outside a villa at Lapa Rios.The last time I visited Osa I was on a small ship that cruised up the Pacific coast from Panama, stopping for just one day to explore a sliver of Corcovado National Park. This time I would get the full rainforest experience, staying for four nights at Lapa Rios Lodge, one of Costa Rica’s first — and most sublime — eco-lodges.

Lapa Rios was established in 1993 when Karen and John Lewis, avid birders from Minnesota, traveled to the Osa Peninsula intent on buying land and conserving it through tourism. “Costa Rica’s leaders knew they had beautiful, remote places full of tropical biodiversity,” Karen told me. “But when we told them what we planned to do, they said that nobody would ever come. Sustainable tourism as a concept didn’t exist back then.”

Inspired by their work in the Peace Corps, the couple forged ahead, developing relationships with the community, building a primary school, hiring local people to build the lodge and, later, training those same people as staff. In 2019, after three decades spent cultivating their vision, which included securing a conservation easement to forever protect Lapa Rios’s 1,000 acres of tropical lowland rainforest, they sold the lodge to longtime Costa Rican conservationists Roberto Fernández and Luz Caceres.

I arrived at Lapa Rios at dusk to find an environment so wild and raw that I could feel it pulsating. The rainforest reverberated with the chirps of thousands of nocturnal creatures. I woke the next morning to sounds coming from the tree beside my window: squirrel monkeys, their little white faces adorned with black goatees, chattering away. Outside my bungalow, one of 17 that sprawl across a ridge above the Pacific, I heard something hitting the ground with a thud. Then I spied a pair of scarlet macaws feasting on beach almonds. They dropped the thick husks onto the path.

Jake Naughton

From left: One of Hotel Nantipa's two-story beachfront villas; sunbathers on Santa Teresa Beach, in front of Hotel Nantipa's Manzú restaurant.The days I spent at Lapa Rios felt like rainforest summer camp, albeit with a dazzling wine list. Each evening during dinner, the lodge’s charismatic concierge, Andres Lopez, outlined the next day’s adventures — an early morning birding tour, a walk to a nearby waterfall, a visit to one of the secluded beaches that wrap around the end of the peninsula. One morning I set out with Danilo Alvarez Seguro, the lodge’s most senior guide, to hike the Ridge Trail. With keen eyes and ears, he identified armies of leaf-cutter ants toiling in the red earth, calamine trees oozing with skin-soothing sap, and tiny poison-dart frogs, their obsidian skins painted in Day-Glo swirls.

On my last evening at Lapa Rios, I sat at the open-air bar chatting with Angel Artavia while he mixed me a mojito with Cacique Guaro, a Costa Rican spirit made with sugarcane. “Once you work in a place like this you see how important it is to take care of nature,” he told me. “You see how everything is connected.” Inspired, Artavia studied biology and conservation basics with Danilo Alvarez Seguro. Now he volunteers with other members of the Lapa Rios staff to teach environmental education in the local schools.

Artavia slid my mojito across the bar. “Pura vida, Gina,” he said. Behind me, the sun dropped toward the Pacific, its final rays threading a light mist with strands of gold. I watched a pair of macaws glide over the ocean and disappear into the canopy. I heard the guttural calls of howler monkeys. Raising my glass, I smiled and took a sip. Pura vida, indeed.

Where to Stay

This 26-room carbon-neutral boutique hotel in the mountains of the Costa Rican cloud forest has been owned by the Belmar family since 1985. It has a microbrewery, lush flower and vegetable gardens, and rooms with sweeping views of the Gulf of Nicoya. Doubles from $319.

In the boho town of Santa Teresa, this collection of 29 breezy suites and villas sits amid tropical rainforest steps from the Pacific Ocean. Doubles from $520.

One of four properties in the Böëna Wilderness Lodges collection, this luxurious eco-resort on the remote Osa Peninsula has 17 airy ocean-view bungalows set within a 1,000-acre private rainforest reserve. Doubles from $1,070, all-inclusive.

Where to Eat

Tuck in to huge plates of casado and arroz con pollo at casem, a nonprofit artisans’ cooperative in the heart of the Monteverde cloud forest. Entrées $5–$10.

This open-air restaurant on Santa Teresa’s main road serves Costa Rican fare like gallo pinto, patacones, and tangy ceviche. Entrées $4–$12.

What to Do

Cabo Blanco Absolute Nature Reserve

Two trails lead though lush, tropical forest at this protected area on the southernmost tip of the Nicoya Peninsula.

Cooking classes, lessons in regenerative agriculture and permaculture, and sea-turtle releases are just a few of the visitor experiences on offer at this environmental-education campus on the Nicoya Peninsula.

At this family-owned, carbon-neutral farm in the hills of Alto Cebadilla, visitors can tour the grounds on horseback before learning about sustainable agriculture, cheese making, and coffee production.

This small, Tico-owned company in Malpaís offers snorkeling, whale watching, and fishing tours in the Gulf of Nicoya.

Monteverde Cloud Forest Biological Reserve

Established in 1972, Monteverde’s first nature reserve protects more than 10,000 acres of pristine cloud forest and provides habitat for 120 species of mammals, 658 species of butterflies, and 425 species of birds, including the resplendent quetzal.

Wander among massive old-growth trees dripping with epiphytes and climb high into the lush canopy of the cloud forest at this 17-acre nature reserve just a few minutes’ drive from Hotel Belmar.

For more Travel & Leisure news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on Travel & Leisure.