How to Eat and Drink Your Way Through Spain's Most Famous Wine Region

Rioja, Spain’s most famous wine region, has long been known for its bold, oaky reds. But a fresh spirit is taking hold.

Gregori Civera

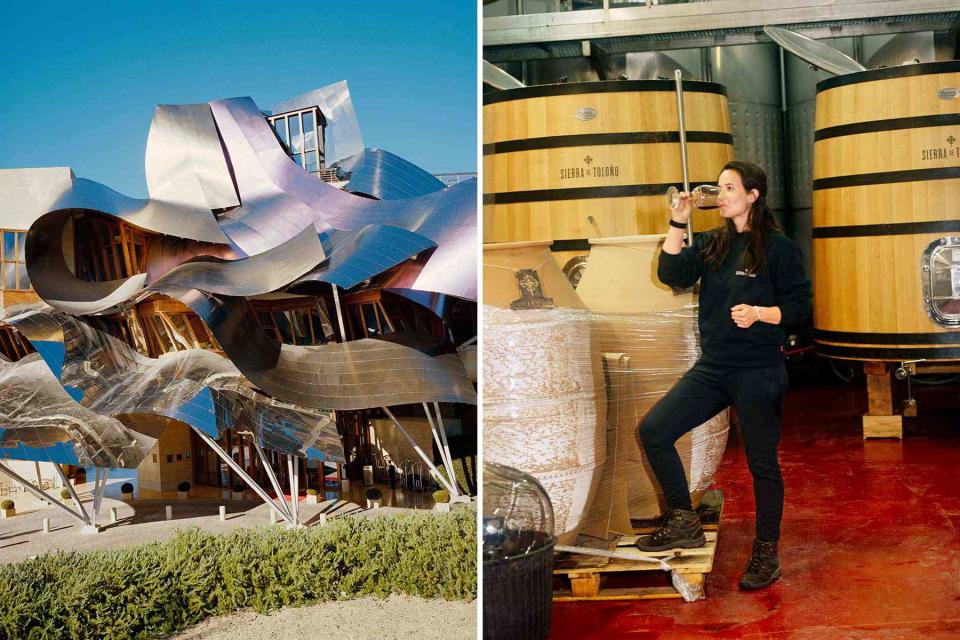

From left: Marqués de Riscal, one of Rioja’s oldest wine estates, is home to a Frank Gehry–designed hotel; Sandra Bravo at her winery, Sierra de Toloño, in the town of Villabuena de Álava.In Rioja, where wine making dates back to the 11th century B.C., the age of the Phoenicians, ancient history is everywhere. If you drive along the Ebro River, which meanders through Rioja and demarcates part of Basque Country, you’ll pass a series of huge Neolithic constructions called dolmens. When you reach the town of Laguardia, you can visit the remains of an Iron Age village that was destroyed by a massacre in the third century B.C. And of course, you’ll find the hundreds of vineyards that make this Spain’s most prestigious wine region.

Age is important here. Since the 1930s, Rioja wines have been labeled according to how long they’ve spent in a barrel: the standards of Crianza, Reserva, or Gran Reserva are aged two, three, and five years, respectively. This contact with oak was always the most important factor, but terroir — that combination of soil, climate, and sense of place so often discussed in the rest of the wine world — was deemed less so.

But now, tastes are shifting. There’s a restlessness among those who see Rioja as stodgy and outdated, your grandfather’s drink. A new generation is making wines for younger oenophiles who want something fresher and fruitier, with lower alcohol and, above all, less oak.

Tensions came to a head last year, when a group of 40 producers on the Basque side of the river petitioned the EU to break away from the Rioja appellation, seeking to label their wines according to where they’re from, not just their age. The industry was stunned — it was like a wine version of Brexit. Though the Basque producers ended up withdrawing their request (for now), the episode was a sign that Rioja’s identity is changing.

Gregori Civera

Pujanza’s vineyards are at the feet of the Sierra de Cantabria mountains.Last summer, I traveled around the region to meet the people shaking things up. It was a dynamic time to visit: the gorgeous Palacio de Samaniego, a hotel in the Basque town of Samaniego, had recently opened. Owned by the Rothschild dynasty, the nine-suite property occupies a restored 18th-century mansion and features works of art from the family collection, plus a restaurant, Tierra y Vino, led by chef Bruno Coelho. The Frank Gehry–designed Hotel Marqués de Riscal, a Luxury Collection Hotel, which opened in the village of Elciego in 2006, had also expanded and made sustainability-focused changes, including a shift to totally organic wine production at its vineyard.

But my first order of business was to meet with Sandra Bravo of Sierra de Toloño, a vintner who exemplifies Rioja’s revolutionary spirit. Though she makes wine on the Basque side, she never considered leaving the appellation — but she still eschews the three classifications, refusing to define her wine by how long it spent in oak. As we tasted her fresh, vibrant wines — a contrast to the heavy style of red that has come to typify the region — Bravo told me that the revolution needs to start from within. “We have to destroy this system and start over again,” she said.

I found a similar philosophy at Bodegas Pujanza, in Laguardia. Lorena Corbacho, the winery’s export director, drove me to its Norte vineyard, which, at nearly 2,400 feet above sea level, was cool and windy. As with Sierra de Toloño’s bottlings, Pujanza’s Norte isn’t labeled by age. “We don’t ever use Crianza, Reserva, and Gran Reserva. That talks only about the barrel,” Corbacho told me. “We keep decreasing the amount of time in oak.”

Gregori Civera

Workers at Bodegas Pujanza, in Laguardia. From left: John Jairo Drada, Íñigo Alonso, Laura León, and Lucía Abando.In the small town of Haro, I loved spending time at the wineries in the Barrio de la Estación, named for the railroad station that was built in the late 19th century to connect Rioja with Bordeaux. In the 1880s, French vines had been devastated by the phylloxera epidemic, so winemakers looked south to Rioja for their grape supply; the wineries in this neighborhood all date from that booming era.

Some in the barrio still hold tight to tradition. In the dining room of the winery La Rioja Alta, I sipped long-aged Gran Reserva with lamb chops grilled over an open fire. “We don’t follow fashions,” Guillermo de Aranzabal Bittner said. He represents the fifth generation of his family to run La Rioja Alta, whose focus has always been on Gran Reservas. “By the time we release our wine, the fashions will have changed.”

But even in this historic neighborhood, there are signs of modernity. A few steps away at R. López de Heredia, I had a half bottle of Viña Todonia 2008 in the 145-year-old courtyard — which also contains a boutique designed by Zaha Hadid. And at Gómez Cruzado, where I tasted a lively blend of tempranillo and garnacha, the young woman pouring the wines said, “This one is a little reckless, a little excited.”

Of course, not everyone agrees with definitions of what is “old” and “new.” I visited Arturo de Miguel of Artuke, in the Basque village of Mañueta. We walked through his vineyards, high above the valley, where he harvests by hand (and even foot-stomps some of the grapes). As we tasted, he pushed back on the idea that this generation was creating a “new” style. “You could consider us as the real traditional style,” he said. “We work the way they did before the phylloxera came to France, before the train came to Rioja.”

Gregori Civera

From left: Freshly harvested Tempranillo grapes at Abel Mendoza winery, in San Vicente de la Sonsierra; the restaurant Tierra y Vino, at Palacio de Samaniego, a boutique hotel in Samaniego.Jade Gross never thought she would move to Rioja. After several years as head chef at the Michelin two-starred Mugaritz, in San Sebastián, Gross, who is Chinese-American, assumed she would end up in France. Now she has several acres of vineyards in the village of San Vicente de la Sonsierra, famous for the ninth-century castle that provides some of the best views in all of Rioja.

One evening, Gross and I did a tapas crawl through Haro, eating pimientos rellenos (alegria peppers stuffed with minced beef) and chanterelles in scrambled eggs at Los Caños and a selection of jamón at Beethoven. Like other young winemakers, she’d been fortunate to be mentored by Abel Mendoza and his wife, Maite Fernandez, the world-renowned, iconoclastic owners of Abel Mendoza, who have always worked against the grain at their vineyard in San Vicente de la Sonsierra. “They’re helping the new generation. I think that’s super important, to continue this way of life, this philosophy,” Gross said. “In Rioja, I think we haven’t even scratched the surface yet.”

A version of this story first appeared in the October 2022 issue of Travel + Leisure under the headline "Vine Shift."

For more Travel & Leisure news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on Travel & Leisure.