Earth's Hidden Eighth Continent Is No Longer Lost

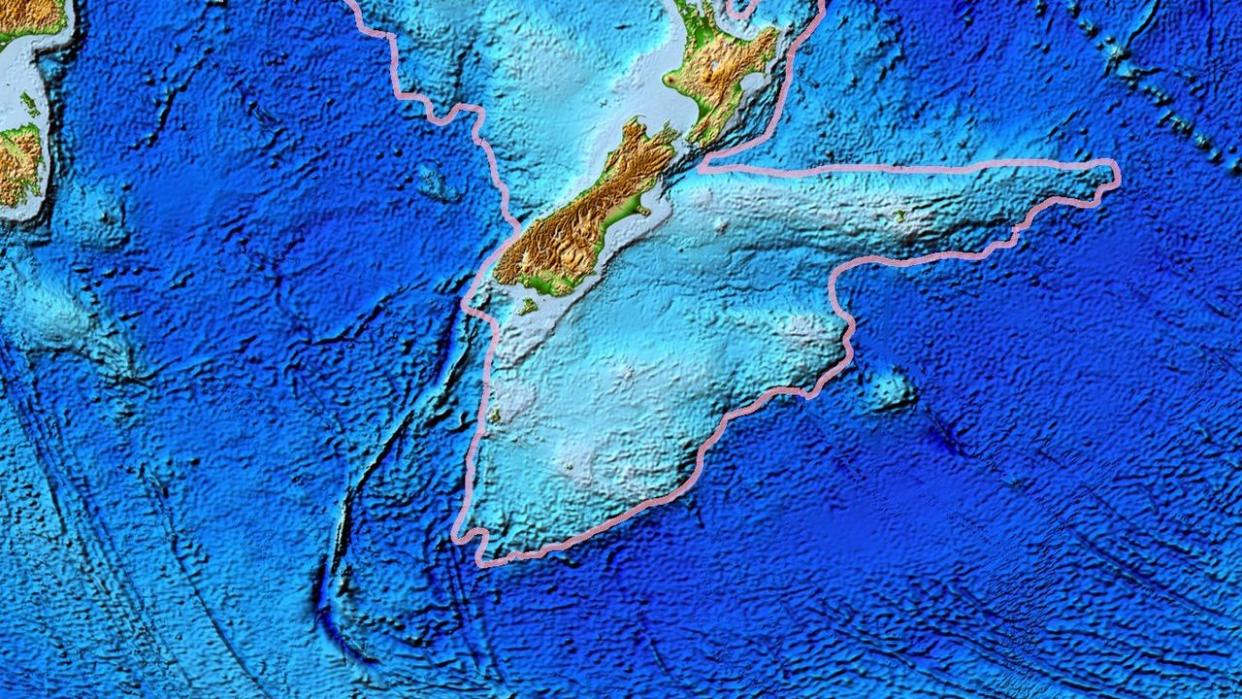

Zealandia, considered a candidate for the Earth’s eighth continent, was mostly lost to the sea.

Geologists say they’ve now mapped the entire nearly two million square miles of the underwater land mass.

The research team used rock samples from the seabed to analyze and date the undersea geology of North Zealandia, the final piece of the Zealandia puzzle.

Zealandia had so much promise as the eighth continent on Earth. Well, it did—until about 95 percent of the mass sunk under the ocean.

While the majority of Zealandia may never host inhabitants—at least, not land-based ones—the would-be continent is now no longer simply lost. Researchers recently finished mapping out the northern two-thirds of Zealandia, wrapping up the documentation of the nearly two million square miles of the submerged land mass.

Get the latest archaeological discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Sign up for our free newsletter and receive a daily digest of the most exciting science news stories in the world. Subscribe for free.

In a study published in Tectonics, researchers from GNS Science of New Zealand document their process of dredging rock samples from the Fairway Ridge to the Coral Sea in order to analyze the rock geochemical and understand the underwater makeup of Zealandia.

Zealandia’s history is quite closely tied to the ancient supercontinent of Gondwana, which broke up hundreds of millions of years ago. Zealandia followed suit—roughly 80 million years ago, according to the latest theory. But unlike neighboring Australia or much of Antarctica, Zealandia largely sunk, leaving only a small portion of what many geologists believe should still be dubbed the eighth continent.

New Zealand makes up the most recognizable above-water portion of Zealandia, although a few other islands in the vicinity are also part of the maybe-continent in question.

The latest research, led by Nick Mortimer, dredged the northern two-thirds of the submerged area, pulling up pebbly and cobbley sandstone, fine-grain sandstone, mudstone, bioclastic limestone, and basaltic lava from a variety of time periods. By dating the rocks and interpreting magnetic anomalies, the researchers wrote, they were able to map the major geological units across North Zealandia. “This work completes offshore reconnaissance geological mapping of the entire Zealandia continent,” they said.

The researchers found the sandstone roughly 95 million years old from the Late Cretaceous period and a mix of granite and volcanic pebbles from up to 130 million years old during the Early Cretaceous period. The basalts are newer—they’re about 40 million years old and from the Eocene period.

Along with the mapping, the paper says that the internal deformation of both Zealandia and West Antarctica show that stretching led to the subduction-style cracking of the plates that welcomed ocean water to form the Tasman Sea. Then, a few million years later, further Antarctica break-away continued to stretch the crust of Zealandia until it thinned enough to break apart and seal the largely underwater fate of Zealandia. This goes against the prevailing theory of a strike-slip breakup.

The team believes, according to Science Alert, that the stretching direction varied by up to 65 degrees, which may have allowed the extensive thinning of the continental crust.

As scientists in New Zealand may tell you, just because Zealandia is largely underwater, doesn’t make it any less of a geological marvel.

You Might Also Like