I E-biked Through Switzerland's Idyllic Emmental Valley on Some of Its Newest Cycling Routes — and Here's Why You Should, Too

In the shadow of the Alps, you'll pass green pastures, country farmhouses, and tiny villages — without breaking too much of a sweat.

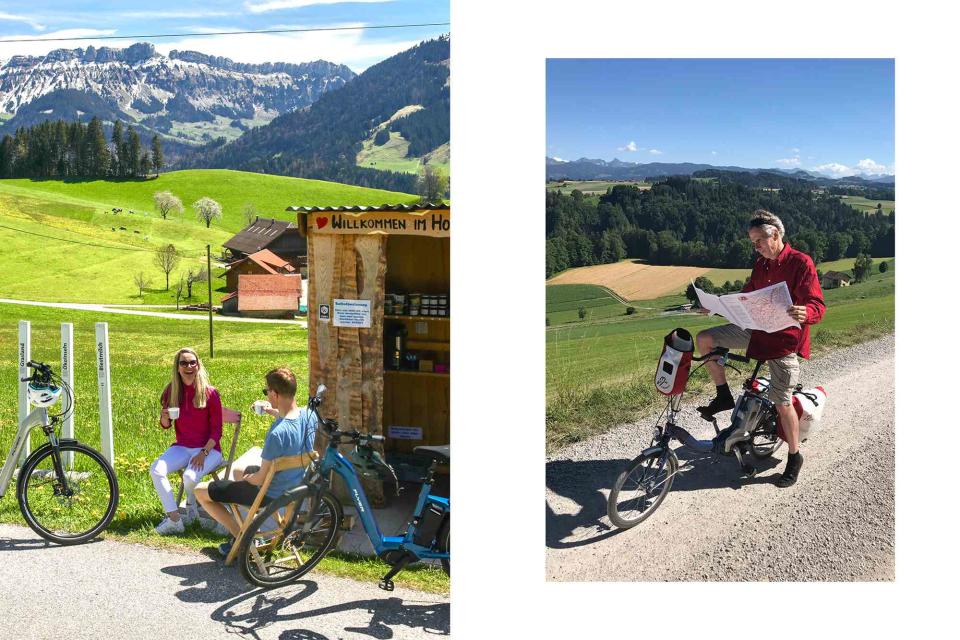

From left: CHRISTOF SONDEREGGER/COURTESY OF HERZROUTE; Courtesy of Paul Hasler

From left: The Rehärze snack and charging kiosk near Schüpfheim; Paul Hasler, one of the founders of the Heart Route, Switzerland's cross-country bike network.Konrad Boss pedaled his e-bike beside me as we emerged from a grove of linden and beech trees. It was a wet September morning in central Switzerland’s Emmental Valley. Feathery clouds drifted over wooden chalets, and cows with bells around their necks grazed in the fields. Boss and I, alone on the road, were lost in conversation. “Sometimes I feel like I’m still too young for an e-bike,” said Boss, a part-time cycling guide who is supremely fit. “But it’s nice to be able to ride and talk.”

The Swiss have enthusiastically embraced e-bike travel, particularly in the Emmental region, a 266-square-mile patchwork of dairy farms, villages, and woodlands in the shadow of the Alps. Over the course of the past two years, the finishing touches were put on a 370-mile network of routes in the area, collectively known as the Hügu Himu (“heavenly hills”). The Hügu Himu is divided into six loops, ranging from 18 to 42 miles long, that run in and out of two of the region’s main towns, Burgdorf and Langnau. The loops take you up sharp hillsides, through pastures, and into hamlets where the air carries a barnyard tang. In between rides, you can fill up on wild mushroom soup at centuries-old restaurants and taverns, and since the loops can be done as day trips, you can return to the same inn each night — no need to lug your bags.

I’d first heard about the Emmental and its quest to become an e-bike haven a decade ago while living in Bern, but it wasn’t until last fall that I returned to see just how far it had come. I picked three loops that, taken over three days, would showcase the soul of the region.

I met Boss at the train station in Burgdorf, where I’d spent the previous night at Burgdorf Castle, a surprisingly well-appointed hostel that occupies an 800-year-old fortress. At the station, those ages 16 and older can rent a Flyer e-bike made right there in the Emmental. I grabbed one and joined Boss for a 30-mile ride east of town. Along the way, grassy lowlands gave way to forests flush with wild chanterelles.

A few miles in, we passed a sprawling farmhouse with 18 tidy front windows and the droopy roof so typical of this part of the country. A woman with flowing gray hair emerged from her doorway and called out, in her singsong Bernese dialect, “Would you like to come in? Perhaps a coffee?”

Some farmers in the Emmental welcome travelers into their homes for homemade pie or cured meats, then send them off with wedges of the region’s famous hole-riddled cheese. I demurred; we’d only been riding for 20 minutes.

“What a pretty farmhouse!” I called out.

“What a pretty farmer!” she joked, waving as we rolled away.

CHRISTOF SONDEREGGER/COURTESY OF HERZROUTE

Cyclists ride e-bikes between Willisau and Burgdorf, in Switzerland's Emmental Valley.The bike’s motors came in handy outside the village of Affoltern im Emmental, where we switched to the highest power setting and rocketed up a steep incline. It was because of this very hill that, in 1993, a man named Philippe Kohlbrenner, who cycled it daily on his commute, fashioned one of the first modern Swiss e-bikes using a car battery and the motor from a windshield wiper. His invention paved the way for the creation of one of Europe’s first successful commercial e-bikes, the Flyer Series C, which helped jump-start today’s worldwide craze.

At the top of the hill, Boss and I stopped to rest on a bench near a monument to 54 Bernese calvalrymen who died in the flu pandemic of 1918. It was a clear day, and we could see three of the most famous Alps: the Eiger, the Mönch, and the Jungfrau. It was spectacular, and it was all ours. By the end of the ride, when I returned the bike in downtown Burgdorf, we’d only been passed by one tractor and four vehicles — and three of those were the same yellow mail van.

In the morning, I packed my things and left the castle to catch the half-hour train to Langnau. There, I checked in to the Hotel Hirschen, a traditional Bernese inn with 18 rooms where I’d stay for the next two nights. Just as I’d done in Burgdorf, I rented a Flyer at the train station and headed out into the countryside, this time with Murielle Blaser, who works for the Emmental tourism board and grew up in the area.

We spent the day riding 23 miles through the hills, with a stop at Kambly, a confectionery and café that makes wildly popular cookies. We zoomed past long sheds packed with tight stacks of cordwood, “the oil of the Emmental,” as locals say, and stopped for a lunch of savory vol-au-vent at Restaurant Blapbach, a hilltop tavern. With energy to spare, we took a side trip to Trub, a picturesque village pinched in a valley where thousands of Anabaptists lived in the 16th century, before many emigrated to the United States to flee persecution. “The Bernese didn’t like how they only served God,” Blaser said.

On my last day, I finally met one of the architects of the Emmental’s e-bike rise. Engineers at Flyer may have perfected the machine, but it was Paul Hasler, an avid cyclist, who gave travelers a reason to ride them.

In the same way the Michelin Guide was created to encourage the French to drive more (and therefore buy more tires), Flyer partnered with Hasler in the early 2000s to plot itineraries that would encourage skeptics to try e-bikes. The plan was brilliant: Flyer set up rental shops at train stations, while Hasler mapped out the most thrilling point-to-points. They stocked restaurants, cafés, and hotels along the way with Flyer e-bike batteries. You could spend the morning riding, stop for quiche and coffee, then swap out a depleted battery for a fresh one, for free, before carrying on.

The Heart Route is now a 450-mile-long trail that stretches from Lake Geneva to Lake Constance, passing through overlooked parts of Switzerland. “I wanted people to have access to places where the Swiss still keep old traditions,” Hasler told me. “It had to be romantic.”

Two decades later, Hasler has also been instrumental in getting the Hügu Himu loops off the ground. (One difference from when he started out? Today, bike batteries last so much longer you can ride all day, making battery swapping obsolete.) Hasler wanted to show me his newest path, a 39-mile-long trek that celebrates one of Switzerland’s most famous novelists, Jeremias Gotthelf, who lived in and wrote about the Emmental in the 1800s.

We set out early, stopping for a lunch of house-made sausage and onion gravy at Restaurant & Hotel Löchlibad and watched farmers parade their cows through town, each animal sporting a crown of Alpine flowers. This is the magic of riding through the Emmental.

“Switzerland’s traditional hot spots are beautiful, of course, but they don’t give you this kind of intimacy,” Hasler told me as we rode off into the hills.

“Here, everything feels so ...” He paused to find the right word. “Heartfelt.”

A version of this story first appeared in the April 2024 issue of Travel + Leisure under the headline "Electric Feel."

For more Travel & Leisure news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on Travel & Leisure.