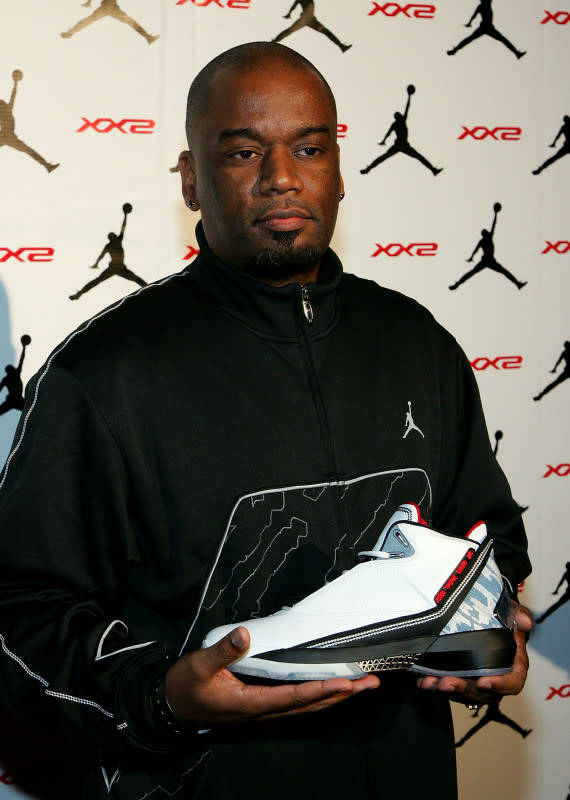

How D'Wayne Edwards Went From Drawing Sneakers, to Working at Nike, to Opening an HBCU for Design

Photo: Ethan Miller/Getty Images

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In our long-running series "How I'm Making It," we talk to people making a living in the fashion and beauty industries about how they broke in and found success.

D'Wayne Edwards never set out to be a designer or an educator, and encountered a number of what seemed at the time like closed doors (like not being able to go to college or having awards rescinded) throughout his life. But somehow, these roadblocks actually led him to major opportunities, such as leading footwear design at Nike and Air Jordan and re-opening a Historically Black College and University (HBCU) as a design school.

"We [have to] look at our journey through a lens of, 'What did I learn from that moment when I thought it was a bad thing?," Edwards tells Fashionista. "It reminds me of a quote Nelson Mandela once said, 'I never lose. I either win or learn.' I believe everything happens for a reason. We just may not find out at that moment."

Edwards has always had a complicated relationship with the words "fashion" and "design". They can silo someone's creativity, he says. That's why at Pensole Lewis College of Business and Design, there's a focus on foundational principles of the practice, before any sort of specialization.

"You go to school for fashion design, product design, industrial design, graphic design, something design," he says. "It just should be design. If you're an aspiring fashion designer, you should be an aspiring designer. You don't want to be pigeonholed."

Keep scrolling to read about Edwards' career, from customizing shoes in high school to designing for Nike and bringing back the Detroit-based Pensole Lewis.

Can you tell me about your relationship with fashion growing up? What about footwear design drew you in?

What's interesting is I didn't know what fashion or design was. I was an artist. I could draw anything I could see, so that's what got me into being creative. When I went to high school, our school uniforms were green and white, and they didn't make Nikes in green and white in the '80s.

I went to a store called Builders Emporium — it's like Home Depot — and got some duct tape and an X-acto blade. There was a shoe repair shop around the corner, and I went and got some green shoe dye. I [thought], if I tape up everything but the swoosh and dye it, let me see what would happen. I did that, and it came out great. I went back to school the next day, and everybody was bugging out. When I saw the reaction people had to the shoes on my feet, it became an addiction. I was like, 'I got to have something fresh on my feet always.'

That turned into a hustle at school where I was doing my teammates' and the girls' basketball team. It just became my thing.

In high school, you submitted something to a design competition. What happened there?

The smallest ad you can place in the L.A. Times, which is a one-inch by a quarter-of-an-inch, said 'Reebok Design Competition' with a phone number. I called, and they said, 'Come down, get the entry form, draw your best version of a shoe and send it to us.' I did that, and waited a good couple months. Then, I get a call, and they say, 'Come down to the office.' I catch the bus to Santa Monica from Inglewood, and they tell me I won and to tell them about myself. When I told them I was still in high school, they wouldn't give me the prize, because the prize was a job — they thought I was a graduate of college. I was like, 'But I won, though?'

How did that feel?

That was the happiest day, the saddest day and probably the most angry I've ever been, in all of about 15 minutes. I promised myself, 'If I ever got into the footwear industry, I'd take it out on Reebok.' I needed that. I needed that push.

Photo: Dimitrios Kambouris/Getty Images

What was your first job in the industry?

My first job in the industry was LA Gear Footwear. I was a file clerk in the accounts payable department, so I wasn't even a full-time employee — I was a temp. About a month in, they put these small wooden suggestion boxes in every department of the company as a way of asking employees to share how they were feeling and what could improve. As a temp employee, I really couldn't say anything, but I was still drawing shoes. I thought, 'Maybe if I put my shoes in the box, somebody will see and want to buy it from me or make it.' So, I decided to put sketches in the box, and did that for six months every day.

About two weeks before my contract was up, the president called my name over the intercom system. I go in, and he had all 180 of my sketches on his desk. He said, 'Tell me more about yourself and what college you go to.' I told him how I just graduated from Inglewood High School seven months ago, and that I can't go to college as the youngest of six kids raised by a single parent. He bought out my contract and hired me at the age of 19. That was Robert Greenberg [who later founded Skechers].

So it was through Robert that you had this starting position. What were some of the biggest lessons in that era?

One was being one of a few Black people in the whole company and not having anybody to talk to, living in two different worlds every day. I would go home, and I couldn't talk about work at home — no one would understand. I go to work, and I can't talk about home at work because no one would understand. It heightened my listening skills and my attention to detail, to what people were doing and saying. It was a switch for me to becoming a student of business and a student of design. I was learning in real time what my job was because I didn't go to college. Everyday was a new adventure. By not being able to have any friends, it allowed me to slow my world down and focus. I wasn't distracted.

What led to your next moves in streetwear?

Robert, about three years in, decided to leave and sell the company. I was devastated because this was my first mentor. I hoped we would get the chance to work together again. I told him, 'If you ever wanted to do anything in fashion, there's some guys I know in downtown L.A. called Cross Colours and Karl Kani doing some stuff on the apparel side.'

I moved to Detroit to work for a small footwear company and saw snow for the first time at 24 years old. About 10 months in, Robert calls and asked me to move back to L.A. since he signed a license to do footwear for Cross Colours and Karl Kani. I moved back to L.A., and became the lead designer. That was in '93. That was my first time in 'apparel fashion'. Streetwear started with those guys, and downtown L.A. was the hub for apparel manufacturing in the United States.

In my early twenties, I was working with Biggie and Tupac and Snoop [Dogg] and Dr. Dre. We were so young, just trying to do something that nobody else was doing. We weren't thinking about the importance of it or that these guys were going to become hip hop royalty. We enjoyed the moment that we were in, because we had, finally, as Black designers, gotten a spotlight.

I learned apparel design, and I was teaching them footwear design. We were trading off on influences and trends and techniques. I understood the idea of not being centralized the way design is centralized now.

Can you take me through the major moments that led you to joining and risking up the ranks at Nike?

It was my work doing Cross Colours and Karl Kani that attracted Nike.

At that time, Timberland was killing everybody, and Nike didn't do boots very well. They needed someone who could do boots. Paul Wilkinson, who worked at Adidas, told me about Drew Greer, who worked at Nike in what was called lifestyle at that time. I flew up to Oregon.

I went to ACG and designed all the boots, including ones still selling today called the Goadome.

I had to learn a whole other skillset when I went to Nike, because, when I was at the smaller company, I was the designer, the marketer, color design, engineer — all of these things. When I got to Nike, I only had to do one. I struggled the first few months. I was so used to doing all those things, but I was pissing off my teammates because I was doing their job. I had to start to do things intentionally wrong so they could catch it and feel like they were helping me, even though I knew what I was doing.

Getting there and being one of six Nike Black designers at the time — at least I had five more people I could talk to. I also met the first Black footwear designer at Nike, Wilson Smith. Wilson started in 1983, and I started in 1989. That was a pivotal moment for me.

I would sneak upstairs to where Jordan was. I offered my help if they needed it, and they took free work. I started doing work with Jordan and ACG at the same time. Within 10 months, Jordan offered me a job. I became a senior designer at Jordan. Three months in, I became design director at Jordan.

From your time at Nike, what led to your foray into education?

I would jump on blogs, like NikeTalk, a famous blog that kids would go to and trash Nike products. There were kids on there who designed sneakers, and they weren't that good, but I could see they had potential. I would jump on as my real name and give feedback. Kids started emailing me.

I started mentoring and developing kids to become interns. I did that for 10 years, working with kids who were in high school or in college, showing them the proper way to design and create. I realized I liked teaching, but there were no schools that taught footwear. I resigned as design director at Nike and took eight weeks off. I told them I didn't know if I was coming back, but that I wanted to test this idea of having a design academy.

How did you get it started?

I basically designed a two-week program based on how we work at Jordan in the most extreme situation, of having two weeks to design something. I paid for 40 kids to take a class at the University of Oregon that I taught. I put them through these two weeks of training — 14 hours every day straight — and they didn't want to leave.

One kid was like, 'Can I write a blog on this?' We ended up having thousands following us and what we were learning every day. This was 2010. That blog got the attention of one of the top design schools in the country called Art Center. They asked if I could teach a class for them. Then Parsons in New York asked. MIT asked. Remember: I'm the kid who didn't go to college.

I did it, but felt weird because I'm a college professor who never actually went to school, yet here I am teaching at some of the best design schools in the world. The way we were teaching it is exactly the way you work, which isn't how school is structured. I was getting results in a tenth of the time it would take normally to educate someone the 'right way'.

I did go back to Jordan for six months. I wanted to finish up whatever I could. I told [Michael Jordan] and all the athletes I was leaving. I felt like I could help more teaching.

I saw the lack of representation, and it wasn't changing... Design school is more expensive than regular school, and, most of the time, Black people are talked out of creative careers, usually by their own parents, because it can be lumped into art, and art isn't seen as a secure career. Nike would recruit at the traditional, predominantly white institutions that have, say, a 2% African American graduation rate. You would've never found me there.

How did all this turn into you reopening an HBCU?

It was an academy, not college. I stayed in Oregon because that's where Nike was, and that's where Adidas was. All our professors are former industry veterans at a high level, and our adjunct instructors are still industry veterans at a high level. We have and had access to some of the best designers in the world. Every kid in that two-week class met their sneaker idol. I needed to put them in front of the people who can give them the job that they want, and I needed to put them in front of the people who are still doing what they want to do at a high level. I did that for 10 years.

In 2020, the world shuts down, and we shut down. One of my alumnae who lives in Detroit tells me casually in conversation that Detroit used to have an HBCU, but it closed. I jumped on Google and started to read about the founder. Dr. Violet Lewis was a Black woman in 1928 who founded a college in Indianapolis with a $50 loan and borrowed typewriters, purely to educate Black women on the skills they needed to work in corporate offices. She started this small school with her own money, it grew, she got investors, and it grew more... In 1987, after moving to Detroit, it received the HBCU designation, making her the second Black woman to found an HBCU ever. Then it started to go backwards.

HBCUs have been historically poorly funded by the government, and her family who took over couldn't advance the curriculum. It closed in 2013. I hear about it in 2020. I called the realtor and asked to speak to the family, and they were open to me acquiring it.

Daniel Gilbert, an owner of Rocket Mortgage, the Cleveland Cavaliers and about 70% of Detroit, had been trying to get me to Detroit for years. His Gilbert Family Foundation was one of our founding partners, as well as the Target Corporation.

The trouble is no HBCU has ever reopened. Several have closed, several have lost accreditation, but none have ever shut doors and reopened. We had to write two state legislative bills of how we're going to reopen and why. It was a technical oversight by the state that they never actually acknowledged on record that Lewis College of Business was an HBCU in the city of Detroit, even though their location is a historical state landmark. Both bills passed in two months; the governor signed it back into law in December 2021. It reopened May 2022.

What role have other partners since had in continuing to advance Pensole?

During the academy, we placed over a hundred designers at Nike. Over a hundred of our students work at Nike now. When I went to Nike saying I was thinking about opening up this historically Black college focused on design, they wanted to know how they could help. The Black Community Commitment and having Nike behind you with anything wakes people up. It woke the industry up like, 'Oh, this is something Nike's investing in. This must be important.'

Photo: Scott Legato/Getty Images

Doors officially opened in 2022. What are your goals for the college?

I would go to 2028 — that's our 100th anniversary. In 2028, you'll be able to walk into those doors and see the history of Black creativity everywhere you walk. What I learned in this journey is: Our story isn't told anywhere. You'll find pieces of it in the Smithsonian, but there's no book, no website that shares the contributions of Black people [to] design and creativity. We're opening Ruth Carter's sample room in a few months. Every room is named after whoever the pioneer was in that industry.

What's your advice to an aspiring footwear design student?

Don't come to me if you're not passionate about it. I can't teach that. We're going to test how bad you want to become a designer in this industry, because our goal is for you to become a designer, nothing before — not footwear designer, not fashion, not apparel, not graphics. Designer, period.

What's the best piece of advice you ever received?

I don't know if it's advice, but a quote comes to mind. I live by Bruce Lee's quote, 'To hell with circumstances — I create opportunities.'

I've had more challenges than successes. I've moved past them because I've have to. Otherwise, I'd be stuck and wouldn't go anywhere.

Like being judged based on what you look like — 99% of the time, I'm in a hoodie or T-shirt, jeans and sneakers. I do that because, first, that's who I am. I'm not trying to pretend to be anything other than what I am. But second, it's a lesson for other people: Don't judge people by the way you see them. I can be in rooms, and no one knows who I am. They'll discount me based on what I look like... The way you present yourself is the way people will perceive you. But as a Black person in this world, I'm always going to be discounted before I get credit for anything. I'd rather be an underdog. You'll never see me coming.

Please note: Occasionally, we use affiliate links on our site. In no way does this affect our editorial decision-making.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Disclosure: Nike paid for Fashionista's travel and accommodations to attend its Black Community Commitment programming, during which this interview took place.

Homepage photo: Cindy Ord/Getty Images

Want the latest fashion industry news first? Sign up for our daily newsletter.