How Dunhill Is Plumbing Its Storied Heritage for a Modern Reinvention

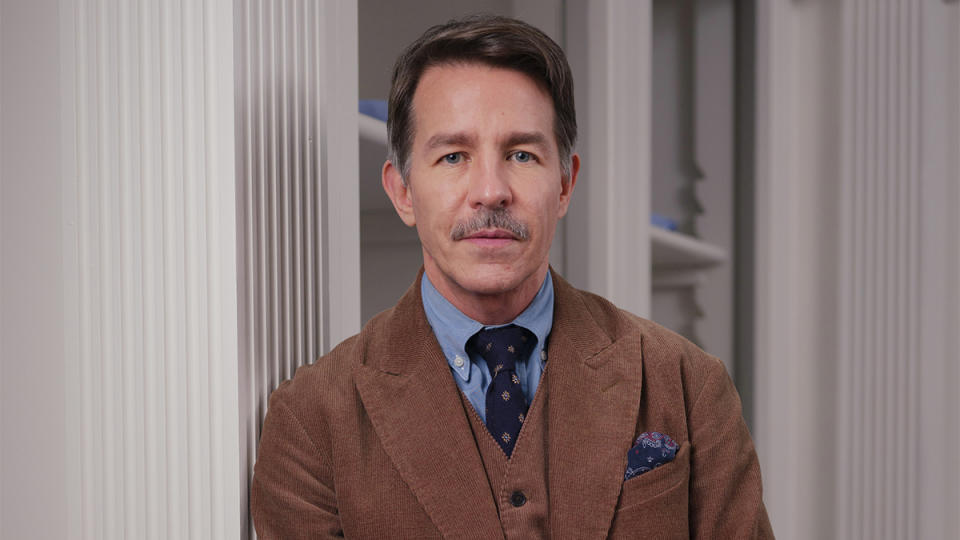

Simon Holloway is the epitome of British elegance. Urbane, considered, and decorous to a fault, he wears a bookish yet chic three-piece corduroy suit, watching the rain teem down on London’s Mayfair. Holloway, above, is the new(ish) chief creative officer of Dunhill, one of the great British luxury houses, with a 130-year history of dazzling innovation, wit, and daring sewn into its DNA, a client list that has included global royalty, Hollywood superstars, and world leaders, and a place in the hearts of sophisticated men the world over.

In many ways, it’s a dream gig and Holloway the ideal hire, but it’s no easy task for a multitude of reasons, not least the series of misguided creative turns by those who came before him, plus the decision by longtime parent company Richemont to tap Dunhill’s last CEO (Laurent Malecaze, the guy who hired Holloway and who had the vision to return the house to its former glory) to take over another of its labels after less than two years in the post. Which makes the job for Holloway, and quite possibly the key to Dunhill’s future success, all the more challenging—and which can be boiled down to this question: How well can he channel a three-inch-tall gargoyle called Tweenie?

More from Robb Report

The Story Behind Callum Turner's Striking 'Masters of the Air' Jacket-and Where to Buy It

The 10 Best Printed Shirts to Add Playfulness to Your Wardrobe

Luxury, Eh? Some of the Biggest Names in Luxury Are Setting up Shop in Vancouver, Canada

This needs some explaining, and to do that, we must understand what Dunhill is and why it matters. Its story begins with Alfred Dunhill, age 21, taking over his father’s saddlery business in London in 1893. Mr. A. Dunhill was revolutionary: A perspicacious entrepreneur and inventor, he foresaw that the age of the horse as the elite’s preferred transport was on the way out, to be replaced by the newfangled motorcar gaining ground in Germany and France. Dunhill built his business designing accessories for this horseless carriage and coined the phrase “Motorities—everything for the car but the motor.”

Over the ensuing years, he innovated on car horns, dashboard clocks, speedometers, and pocket voltmeters and designed various items of clothing for drivers, such as long gloves and extravagant outerwear made of Siberian wolf fur or sealskin that fastened around the neck to keep the British weather in abeyance. And in a fit of pique, after being stopped in his car by the police doing 22.5 mph—way above the 12 mph limit at the time—Dunhill created mini binoculars, worn like spectacles, called Bobby Finders, after the nickname for English police of the period. These, so the advertising literature claimed, allowed Edwardian motorists to “spot a policeman at half a mile even if disguised as a respectable man.”

Which is where our friend Tweenie Devil comes in. He was a Dunhill mascot and hood ornament introduced in 1913, complete with cloven feet and horns, blowing a raspberry at local law enforcement. And it’s this sense of mischief, humor, and exuberance, married to exceptional craftsmanship, luxury materials, and ingenuity, for which Dunhill became heralded.

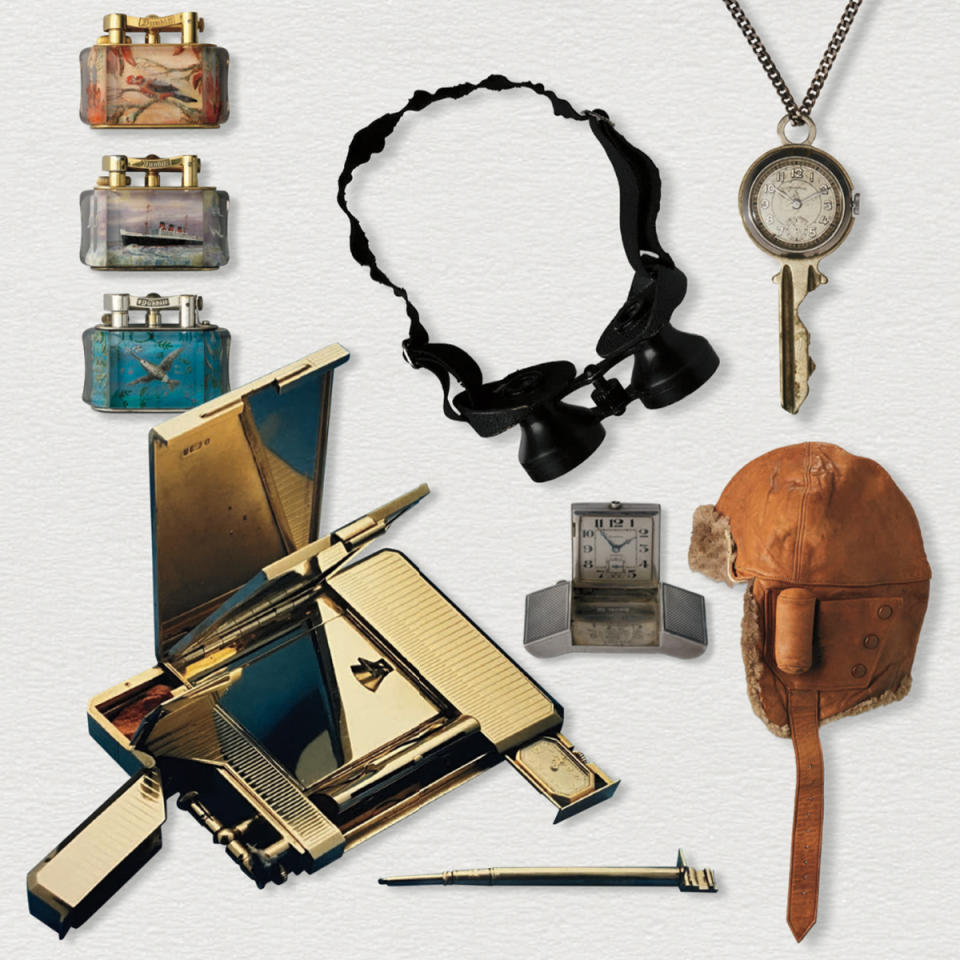

In the hundred years since first opening a store in New York in 1922, the Dunhill brand went around the world. It was famous for pipes, including a clever design with a hood on the bowl to protect it from the wind, and for beautiful Art Deco lighters with a patented horizontal flint wheel that allowed for single-handed operation; hugely desirable then, they’re collectors’ items now. In fact, the Jazz Age was Dunhill’s golden period, full of chic and inventive designs such as a watch set in a belt buckle for sports, another inside a key, one atop a pen, and yet others, called captive watches, where the dials popped out of ornamental cases. There were cocktail sets for the traveling drinker (or the drinking traveler), compendiums that included cigarette cases, lighters, clocks, and pill boxes, and, since 1930, exquisite writing instruments produced by the Japanese lacquer specialist Namiki.

Customers included the Duke of Windsor, members of the celebrated “Bentley Boys” racing team, Cary Grant, Picasso, and Marlene Dietrich, as well as British prime ministers Neville Chamberlain and Winston Churchill—and, later, Queen Elizabeth II, Frank Sinatra, and Truman Capote, who wore a bespoke Dunhill tuxedo to his famous Black and White Ball in 1966. In that same year, the brand opened a store in Hong Kong, its first in Asia; not long afterward, its ready-to-wear collection debuted. Around the time of its centenary in 1993, Dunhill had just shy of 100 stores globally, which soon rose to 160 by 1998. Alfred Dunhill would have been proud.

But all was not entirely well. According to a senior figure who was there during the 2000s, Dunhill was losing millions with a client base bordering on the pensionable. Various creative directors were recruited to attract younger consumers: Kim Jones, now at Dior, won the British Fashion Council award for menswear designer of the year during his stint at Dunhill, straddling the line between fashion-forward and classic tailoring; John Ray then leaned into the traditional before being replaced in 2017 by Mark Weston, who pointed the brand in a more avant-garde direction, with split-hemmed trousers paired with wrapped double-breasted jackets that aggressively subverted the house’s tailoring toward an edgier, Asian customer. While it got the brand noticed, it was not a commercial success.

So in February 2022, reinvention came to Dunhill once more, with the appointment of Laurent Malecaze, 37, as CEO. Dunhill’s annual report for fiscal year 2023 showed revenue at £36.3 million, or about $46 million, with an operating loss of £38 million, or roughly $48 million. Weston left the company in January 2023. While luxury observers could have been forgiven for rolling their eyes and thinking, “Here we go again,” Dunhill enjoys significant affection within the industry, where it’s seen as the British Hermès, even if a somewhat dormant one. There’s a belief that the brand can rise again, and the team of industry veterans brought in by Malecaze and Holloway is considered well-placed to bring that about.

It’s one of the great houses of Britain, and there aren’t that many of those scalable, historic houses in London anymore—it’s stood the test of time.

Over the course of several conversations during the past year while Malecaze was still in his post (he has since taken the helm of the Chloé fashion house), he told me of his plans to bring the focus at Dunhill back to its historical strengths: realigning it with motoring; returning to elegant, high-quality ready-to-wear with a timeless aesthetic, matched with in-house bespoke tailoring; reintroducing desirable hard goods such as 2023’s release of a contemporary “compendium”; and doubling down on the brand’s bespoke leather goods, what Holloway calls the house’s leather signature, made at its London factory. The irony of a young Frenchman being charged with bringing a historic British brand back into competition with the best of France’s luxury companies was not lost on Malecaze; indeed, I think he rather liked it. And while a new CEO will be appointed (chief operating and financial officer Andrew Holmes has taken the seat for now), the message from Richemont, predictably, is that the groundwork has been laid and the vision remains as it was. “Laurent has made a great contribution over the past two years at Dunhill, a key maison for Richemont,” says Philippe Fortunato, Richemont CEO of fashion and accessories. “The next leader of Dunhill will be announced in due time. With the very strong team already in place, the maison is in good hands to open a successful new chapter of its rich history.”

Let’s hope. While 2023 was a challenging year for many in the luxury world, the top end of the market bucked this trend. LVMH posted end-of-year results with revenue at €86.2 million (roughly $93.2 million) with growth of 13 percent compared to 2022, while Hermès’s Q3 results, its most recent disclosed at the time of writing, showed an increase in revenue of 17 percent. The opportunity is certainly there for Dunhill, but stability is key. It cannot afford a new CEO determined to make their mark by changing course.

The brand may now be owned by a French conglomerate, but its success is a matter of importance in its home country. British luxury needs a star performer, particularly in menswear. Burberry, which is admittedly more of a fashion label, recently reported retail revenue down 7 percent year-over-year, with economists citing rising inflation and economic uncertainty adding to a post-pandemic slowdown in certain categories. There are smaller British menswear brands that project a similar poise, such as Thom Sweeney, but nothing on the scale that Dunhill can propose.

Helen Brocklebank, CEO of Walpole, the trade group for British luxury, is upbeat on the prospect. “Currently there is no global luxury menswear brand, and it’s a Dunhill-shaped hole,” she says. “When it comes to style, Britain’s superstrength is menswear: It gave the suit, raincoat, brogue, trench coat, and even the dinner jacket to the world, along with an enduring, defining, and highly exportable sense of masculine style.” She does, however, sound a note of caution—one that’s been echoed by a number of industry insiders I spoke to for this piece. “The key to unlocking the opportunity of filling that No. 1 global luxury-menswear-brand spot is consistency, and it will require investment,” she says. If Richemont is serious about propelling Dunhill to the top of the tree, it is not a one-, two-, or even five-year agenda. It’s Project Long Haul.

So right now, the future is Holloway’s to shape. “On paper, I have quite a bizarre CV,” he says. “I’ve worked in menswear, womenswear, shoes, and fragrance. Along the way I’ve collected quite a lot of information, and now I’m trying to draw deeply into every experience I’ve ever had.” Holloway, 52, is certainly well traveled, having held design posts in Italy, France, and the U.S. at major labels such as Richemont stablemate Purdey, as well as Ralph Lauren, Jimmy Choo, Agnona, and Narciso Rodriguez. For him, the key to elevating Dunhill is sophistication in every detail, from fabrication to storytelling.

“Dunhill is urbane, a kind of visual essay of classicism, but it has the potential to have a beautiful casual expression as well,” he says. “It’s one of the great storied houses of Britain, and there aren’t that many of those scalable, historic houses in London anymore—it’s stood the test of time.” To be offered the role, he says, “felt exciting, like an extremely special and unusual opportunity, one that comes with a great sense of responsibility to get right but also with the opportunity to create something really quite useful.”

Holloway is engaging company. Originally from Newcastle in the north of England, he now has the non-regional accent of the international Brit. Words like “contemporaneity,” “relevance,” “evolution,” “fit,” “progression,” and “proportion” all strike the right note, but it’s when he references British or Italian fabric mills by name, or speaks of sitting with makers who have been honing their craft for decades, that you get the sense of a lifetime’s work about to be unleashed, albeit it in subtle, understated ways. His version of Dunhill contains contradictions: Like Malecaze, he wants the brand to return to core competencies, to a more exclusive sandbox within which to play, but once there he feels there’s huge latitude to develop and explore.

“I think if you’re going to ignore your code and your heritage, you better have something pretty amazing to replace that with,” he says, with perhaps a gentle dig at what came before. “I just don’t see that as necessary here. Because the incredibly precious thing about Dunhill is that there is all of this amazing heritage and storytelling, and it’s true heritage. It’s not manufactured.”

As we look through pieces from his first pre-collection, to be released in the coming months, Holloway scrunches a sleeve or pulls a shirt-jacket-coat combination together to make a point. “My vision here is ageless,” he says. “Every look could be worn by any of our clients and be appropriate. There’s a young audience for heritage that are thirsty for pattern and tradition. The richness that this house can provide [in fabrication] is really exciting and feels new to them, like an unexpected find. And there are men of different ages that appreciate classicism but want a contemporary spin. Because nobody wants to look old. I’m not interested in making dusty, English, heavy clothes—it has to be light, wearable, and modern.”

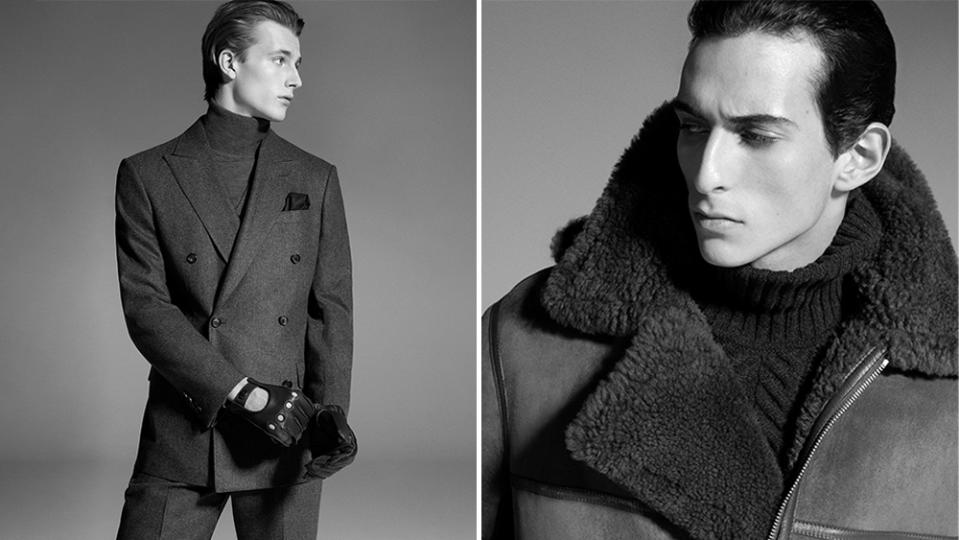

While only a handful of looks from the pre-collection are available to view at the time of our interview, I see more of the vision take shape a few weeks later, when the full collection is revealed to buyers in Milan during fashion week. It’s everything Holloway promised: ageless but relevant. Archival elements are recontextualized in exceptional fabrics, such as a soft leather overcoat or velvet slippers with (hurrah!) embroidered Tweenies. Outerwear, a key component of Dunhill’s ready-to-wear since those Siberian wolf coats 120 years ago, is a standout: beautiful shearling jackets with vast hoods, parkas that nod to mod counterculture but wouldn’t look out of place on Kendall Roy, and sweeping double-faced cashmere overcoats. The tailoring is chic, and unexpected pleasures are to be found in V-neck sweaters with a new Dunhill monogram and in knitted-jersey double-breasted cardigans—relaxed but refined, they are pieces that could define casual elegance and become instant favorites.

There’s a confidence to Holloway that will no doubt serve him well during this Dunhill adventure. When, remarking on the breadth of his remit, I reference a set of striking vintage light fixtures he’s just installed in the London flagship in Bourdon House, he responds: “I feel quite self-assured in my decision-making from subject to subject, from furniture to the shirt and tie, that it all has to come from a similar point of view. It’s an almost extreme sense of classicism, but redacted and edited to feel right in the moment. It can’t be boring. I want it to feel much like when you walk into a beautiful English grand hotel that happens to have a very modern bedroom or bathroom. You don’t really want the old plumbing, as charming as it may have been.”

Bourdon House is one of Dunhill’s secret weapons. The Georgian mansion, once the home of the second Duke of Westminster and Coco Chanel, is the only free-standing building in Mayfair and contains not just the clothing, footwear, and accessories collections but also a hairdresser, humidor, and bar. Attached is Alfred’s, a members club with a smattering of bedrooms available. It’s both a historical representation of Dunhill’s pedigree and a lure to international clients and the local C-suite crowd, who dine in the airy restaurant and can while away an afternoon in comfort in the lounge.

Upstairs is where the bespoke tailors work their shears, with fabric bolts, paper patterns, and half-completed suits adorning almost every surface. One of the elements that makes Dunhill unusual, not just among British luxury brands but across the global luxury landscape, is its bespoke offering. Many fashion houses in Europe, for example, have a made-to-measure tailoring service in which a standard pattern is modified to fit your frame, but exceedingly few can provide genuine bespoke: using a pat- tern based entirely on your measurements, begun from scratch, not adapted from a house block.

Will Adams, 48, is bespoke tailoring director. He’s worked on Savile Row at Kilgour and Hardy Amies and his outlook dovetails with Holloway’s contemporary classicism. He believes Bourdon House’s relaxed feel—where you might pick up a cigar from the humidor after a long lunch, smoke in the garden, and read the paper while you wait for your appointment with the tailor—married to the house’s more modern interpretation of British menswear (lightweight, without too much padding and layers, using exclusive textiles) offers a counterpoint to what is available on the Row: an experience, not a transaction.

Dunhill’s tailors currently travel to America three times a year, visiting New York, Palm Beach, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Washington, D.C. There’s a strong client base in Japan and China and a refreshing “anything goes” feel to the operation, which is what bespoke should be about. “One of our Japanese clients brought in a Patagonia fleece that he wanted replicated in a double-face cashmere,” says Adams. “We were like, ‘Yeah, why not?’ I mean, it’s kind of fun for us. And it looked really cool.”

The bespoke process is relaxed and comfortable, with no formality or stuffiness, traits still too common within some tailoring shops. Adams is ready with advice but not pushy. To his mind, the advantage of not having a definitive house style, as others on the Row do, is that you’re not propelled in any particular direction, so you’re more likely to get what you want.

“There are a lot of interesting fabrications and textures available, from silk and wool blends to bamboo,” he says. “Our clients aren’t just coming for a classic navy or gray suit. They might have those for business, but now they want a soft flannel blazer and a couple of pairs of flannel trousers.”

Another point of difference is the factory, hidden away in Walthamstow in northeast London, where Dunhill’s leather goods (among other things) are made. Master craftsman Tomasz Nosarzewski, 62, has been here for over 40 years and now oversees bespoke orders. Folio cases that look like envelopes are going into production, a riff on vintage cigarette-case designs from the archive. Dunhill’s bespoke luggage extends to bags, briefcases, and small pieces, with client requests often including designs for Apple AirTags to be incorporated into everything from glasses cases to wallets.

Nobody wants to look old. I’m not interested in making dusty, English, heavy clothes—it has to be light, wearable, and modern.

Each item is made by a single person from start to finish, often entirely by hand, which can take 25 hours or more. Designs are sketched, then prototyped in salpa, a cardboard-like composite that allows the basic structure to be tested. But translating that into leather, a far more challenging and expensive material to manufacture, takes the engineering minds of the master leather-workers, who must problem-solve in 3-D as they go. At the time of my visit, a bespoke bag with a very particular set of pocket requirements was being workshopped to include the perfect compartment for the client’s daily newspaper along with additional ones specific to phone, keys, and other essentials. Even in salpa it was beautiful: a sizable yet sophisticated tote that you’d imagine, in the fullness of time, would be gleefully accepted by a family member as an heirloom.

The archive, with wooden shelving holding vintage globes, doctor’s bags, car headlamps, and old film from a long-forgotten fragrance commercial, is a rummager’s delight and further proof of the lasting power of fine design. Drawer upon drawer reveals antique pens, watches, clocks, cuff links, medals, lighters, more hood ornaments including a bulldog and assorted devils, a complete set of maps for the early British motorist, and a full dining set in a hamper. If inspiration for Dunhill’s future cannot be found here, then inspiration does not exist.

After years of navigating various misadventures, it does appear that Dunhill may be heading for calmer waters. It’s early days, of course, and Holloway’s debut collection is still some months from reaching stores, but he has everything he needs. The question is: How far will he go? In order for the brand to stand apart from the Loro Pianas, the Hermèses, and the Ralph Laurens of the world, I can’t help feeling that it’s Tweenie who still holds the key. Innovation was integral to Alfred Dunhill’s success and should be to Holloway’s stewardship of the name all these years later. A point of view, a reason for being, is everything. So dial up the devilry. Market the mischief. It’s all there in the archive. As Holloway himself says, “As a designer you get asked, ‘What’s your inspiration?’ The inspiration here is Dunhill. It’s so interesting and cool and unexpected, why wouldn’t it be?”

Best of Robb Report

Sign up for Robb Report's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.