He dug up one decades-old class ring after another, then reunited each with its owner. How?

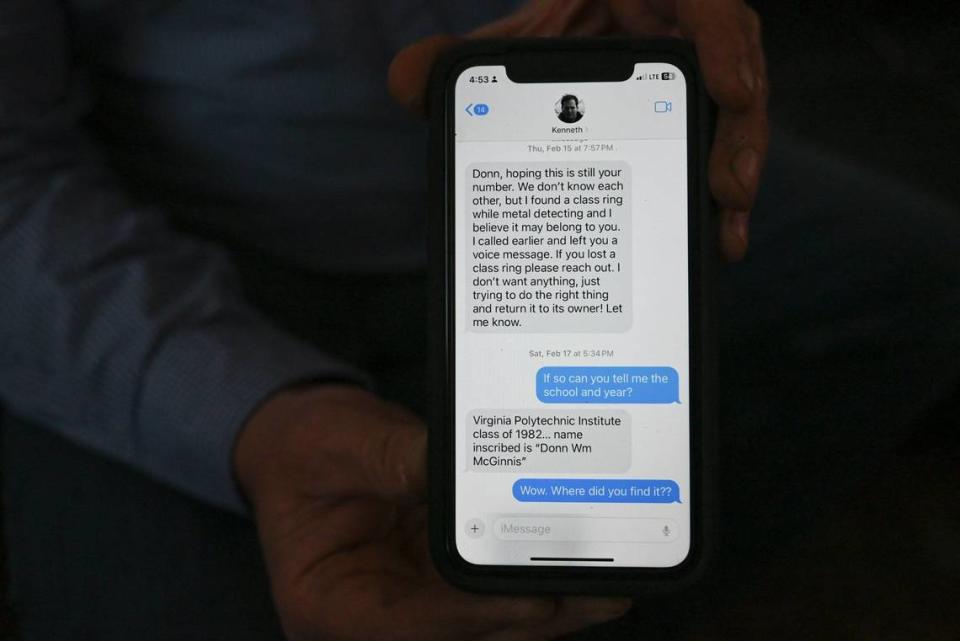

The text came on a Saturday night back in mid-February, from a phone number with an area code linked to Arizona. But Donn McGinnis regarded it as though it had come from Mars.

Or from somebody messing with him, or — worse — somebody trying to swindle him. It just seemed so outrageous.

“We don’t know each other, but I found a class ring while metal detecting,” said the text, which the Denver, North Carolina resident had left unread for nearly two days before he finally opened it while waiting for a table at a restaurant with his wife Susan. And the anonymous sender had included a mind-melting kicker:

“I believe it may belong to you.”

Completely baffled, Donn had Susan take a look at his phone. Well, she told him after reading it over, at least he spelled your name right. With two “n’s,” and not one.

So after a little hemming and hawing and a lot of concern still that this was some sort of trick, Donn decided to engage, warily.

“If so,” he typed back, flatly, “can you tell me the school and year?”

A disembodied answer came quickly: “Virginia Polytechnic Institute class of 1982... name inscribed is ‘Donn Wm McGinnis.’”

In an instant, a potent mixture of pleasurable and painful memories flooded through him.

His mother offering to give him several hundred dollars for the gold ring he wanted so badly to mark his graduation, even though she could barely afford it. His habit of wearing it proudly through most of the ’80s and ’90s, virtually all the time, except when sleeping, washing his hands when they were really dirty, or playing golf. The day he lost it more than 25 years ago, somehow, somewhere, on a golf course in Charlotte. Breaking the news to his mom. Her trying to cheer him up by saying maybe it would turn up. Her passing, barely a year later, in 1999.

An instant later, Donn’s eyes widened and his jaw dropped as his brain clicked. He looked at Susan and said to her — almost in disbelief of the words coming out of his own mouth — This guy’s got my ring.

It was a ring he’d treasured. That symbolized his mom’s love for him. That he long ago had given up on. That now some stranger, for some strange reason, perhaps wanted to give him back. Donn needed a minute to collect himself, then he hit the call button on the Arizona number, armed already with a thousand questions. But mainly with these two: Where in the world did this person find it, and how much did they want for it?

The answers to both were ones he never would have expected.

‘Well, this is gonna sound weird...’

Ken Brooks got his first metal detector as a gift from his wife Yulia and their three children back when they were living in Gilbert, Arizona.

It was nothing fancy, and he did nothing fancy with it, other than poke around their front yard.

But then a couple Christmases ago — a few years after Brooks had taken a new job that brought his family across the country to Concord — his brother also got one as a gift from his own family, became hooked on the hobby, and began sending Ken photos of old coins and other assorted relics as he found them.

This, finally, inspired Ken to dust off his cheap detector, to venture beyond his own yard. And this time, he stuck with it, partly because he’d always liked history and geography, antiques and collectibles, partly because he saw it as a chance to be less sedentary.

In the spring of last year, he upgraded to a nicer model. He discovered and joined the High Point-based Old North State Detectorists club, and the South Carolina Metal Detector and Relic Association in Rock Hill, South Carolina. He started participating in those groups’ “hunts,” which saw members combing areas of historic sites or private properties through partnerships with the landowners.

Before long, he was addicted, too.

Then last August, more than six months before he would be introduced to the name “Donn Wm. McGinnis,” Ken would find and return his first very old class ring.

On this particular day, he was on an organized “hunt” with the High Point club, sweeping a 500-acre site in the Greensboro suburb of Jamestown that had been proposed for residential development. The hope was to find evidence of Civil War-era gun manufacturing, but the truth was that finding anything of even modest interest would have made them happy.

Well, Ken wound up striking gold. Literally.

In the front yard of a vacant home, his detector chirped a promising tone over a spot of earth that he would carefully dig into with a special type of shovel (designed to minimize traces of digging or damage to the ground) to produce a “plug” of dirt from which a ring peeked through.

Ken pulled it out and cleaned it up a little to reveal details — Ragsdale High, 1989, a golfer, the name Ellis. Then on the inside, a full name was inscribed: Ellis Von Cannon.

Via a simple Google search, the correct assumption that there weren’t many Ellis Von Cannons in the world, and the help of a club member with easy access to public records, Ken had a phone number.

He called from the parking lot, and much to his surprise, someone actually picked up.

Is this Ellis Von Cannon? Ken asked. Yes, it is, the man replied.

OK, well, this is gonna sound weird, Ken said, then he quickly added: I’m not selling anything. I think I might have found something you might have lost. Your class ring.

Ellis Von Cannon remembers feeling like his heart had suddenly stopped beating in his chest.

“And you probably can’t print this,” Ellis recalls, “but my response to him was, ‘You’re s------- me.’”

A ring his dad didn’t want to buy

Ellis has a vivid memory of the last time he’d seen his pricey class ring, which he’d had to beg his dad to buy for him.

It was October 1988, he was in his junior year at Ragsdale High School in Jamestown, he’d had the ring for only about a month, and he was at a friend’s house for a French club meeting during which they were preparing boutonnieres and corsages for Homecoming.

After a few hours of handling flowers, hanging out and having laughs, Ellis hopped into his car to head home. But as he was easing down the driveway, he ran his thumb over the finger that he’d been wearing the ring on — to discover that it was no longer there.

He immediately panicked.

He tore the car apart, found nothing. He drove back up the driveway, tore the house apart with his friend, his friend’s mom and his friend’s brother, found nothing. Looked through every room, under every sofa cushion, in every crevice, even in the trash, found nothing. He thought he was going to be sick.

This ring that his father didn’t want to buy was, apparently, gone.

It never turned up. Eventually, his parents did buy him a replacement, but this time they got a fake-gold version that was more chunky and less elegant. Ellis didn’t like it nearly as much, and by college it basically never went onto his finger again.

Thirty-five years passed.

He’s now 52, living in Florida, working in hotel operations for Royal Caribbean International. In fact, last August, he was vacationing in Europe on one of his company’s cruise ships when he was blindsided by the phone call from Ken Brooks.

Ken explained that, no, he was not (kidding) him.

He asked Ellis where he lost his ring, and Ellis told Ken where his friend had lived at the time. As it turned out, Ken had found it under about three inches of dirt out by the back door of this same home. The ring had been there all along.

Ownership having been verified, Ken cheerfully said he would ship it to him from North Carolina, ASAP. Ellis told him he’d love that, and offered to pay the costs, but Ken refused to accept any money. Ellis couldn’t thank him enough. Then, after they hung up with each other, Ellis promptly made another call.

His father broke down in tears as Ellis told him the story.

Less than a week later, the ring arrived in Miami Beach in sparkling condition, because Ken had taken it to a Jared store to get it cleaned. “It looked,” Ellis says, “as good as it looked when I lost it 35 years ago.”

Asked what it means to him, he says, “I look at the ring, and I don’t think about the French club and high school as much as I think about Ken doing the right thing, and it lifts my spirits. ... There’s good people out there still. Human beings treating each other right and living by the Golden Rule. That’s more of what this ring represents to me now than four years at Ragsdale High School.”

By the way, if you’re wondering how often this kind of thing happens — a treasure, unearthed with a metal detector after having been missing for decades, marked by enough information to track down the original owner — the answer is:

“It is very rare,” says Rodney Joslin, who has been president of The Old North State Detectorists since 2015. In about 30 years of detecting, he’s found and returned just one class ring.

Meanwhile, in the span of just six months, Ken has found and returned not one, not two, but three.

‘Do you want me to pay for it?’

The first minute or two of that call Donn McGinnis made to Ken from the restaurant in February was a bit awkward.

“We were both trying to feel each other out,” Donn recalls. “I was trying to figure out if he was pranking me or doing something scamming me, and he was trying to make sure it was my ring. So we were asking each other questions — I said, ‘What color is the stone?’ He said, ‘Well, what do you think it is?’ ‘It’s a garnet.’ He said, ‘I don’t know what color that is.’ I said, ‘It’s maroon. That’s a Virginia Tech color.’ Then I said, ‘There’s something unique about it. It’s got VPI etched in the top of the stone.’”

Now Ken was sure. I’ve got your ring, he told Donn.

Ken went on to explain that he’d found it six inches beneath the surface of a sand volleyball court at a park in the Mallard Creek area. Donn was astonished; he relayed that he’d lost it at a golf course in another part of Charlotte, didn’t remember ever having been to that park, and definitely was not a volleyball player.

It would have to remain a mystery how it had made its way to that resting place.

At this point in the call, Donn was scratching his head. Well, uh, what do you want to do with it?, he asked Ken.

I want to give it back to you, Ken said.

Do you want me to pay for it?, Donn asked.

No! I just want you to have it, Ken replied.

Before they ended their conversation, Donn suggested they try to connect the following week. He underestimated his excitement, however, and the next day asked Ken if he could meet him and his wife at the Full Moon Oyster Bar in Concord. If Ken would bring the ring, they’d buy him dinner. Ken declined the offer of a free meal but said he’d be happy to deliver the item he found.

They wound up talking at the restaurant for two hours, and during that meeting, Ken showed Donn another graduation ring he’d found just one day earlier behind a Lowes Foods store where the old Harrisburg High School once stood. It was a women’s style — belonging to someone from Appalachian State University’s Class of 1969 — and wasn’t inscribed with a full name, only initials. Ken doubted he’d be able to find the owner.

But the following day, Ken says, he actually did.

Big finds — and big losses, too

With help from one of his High Point club’s best detectives, Ken was able to ascertain that the original owner of the ring was a woman who lived less than 10 minutes away from him in Concord.

After being unable to reach her by phone, he decided to simply drop by with the ring.

To make a long story short, The Charlotte Observer also connected with this woman, who says the inscribed initials match her maiden ones; who says she did graduate from App State in 1969; who says she did have a class ring that went missing; and who says she was indeed visited by Ken Brooks. She says Ken insisted the ring was hers, so she ultimately accepted it. But in a phone call with the Observer, she said that while “I’ll treasure it,” she did not believe it to be her ring.

Ken, on the other hand, is certain it’s back with its original owner.

Donn would probably agree, but he thinks all of this is somewhat beside the point. The main point of all of this, he says, closely echoes what Ellis Von Cannon said.

“Ken did the right thing. With the prices of gold, he could have gotten a lot of money for these rings. But Ken did the right thing, and when people do the right thing, this is what happens. I mean, the feeling of figuring out that he had my ring, it was amazing. I was just unbelievably elated.”

For his part, Ken can tend to try to downplay that notion. “I’m just a guy who found some rings in the dirt. Had I left it at that, that’s really all they would have been.”

At the same time, he can tend to see the bigger picture. “However, it’s my hope that reuniting the rings allows their stories to continue and perhaps take on new and deeper meanings, meanings that will be different for Donn and the others. It adds meaning for me as well. It provides me a real-life parable of sorts, a testament of redemption, recovery, restoration and hope. ...

“You don’t have to consider yourself a person of faith to have faith and hope in redemption, renewal and recovery, that we can be made whole again. We can hold on to the hope that our stories are not finished.”

As for his knack for making noteworthy discoveries in the first place? He simply attributes it to consistency and persistence. “I go out,” he says, “almost every day.”

Which brings us to the final little surprise in this story:

When metal-detecting fully got its hooks into him last year, it was May. “It was already getting hot,” Ken recalls, “and I was sweating, and I thought to myself, ‘Well, this is good. I’m exercising.’” In the year since, between the many hours a week he’s spent walking around carrying his detector and his decision to start intermittent fasting, Ken says he’s dropped about 120 pounds.

Unlike the treasures he’s found, though, he’d like to believe that the weight will stay lost forever.