How Drakeo the Ruler Made One of the Albums of the Year From Prison

On the phone from L.A.’s Men’s Central Jail on a Wednesday afternoon, Drakeo the Ruler says, “My judge has coronavirus. I’m trying to figure out what’s going on. I’m supposed to be in court on Friday. But my judge has coronavirus. What are the odds of that?”

Then, as he does with improbable regularity, he starts laughing, loudly and warmly. “What are the odds of that, bro? Two days before court? Like—what?”

In the years since breaking out as the inimitable new star of California rap, Drakeo, 26, has been through a legal nightmare. In 2019, he was acquitted on charges of murder, attempted murder, and conspiracy to commit murder. Rather than dropping the case, however, the L.A. district attorney decided to reprosecute Drakeo on two “gang”-related charges that the jury had been hung on. His case has become a nexus of notorious prosecutorial tactics: the “institutional racism” of California’s gang laws, and the mind-boggling use of rap lyrics as evidence. Drakeo has been incarcerated ever since; he’s facing 25 years to life.

Now, in the latest twist, his case is stalled by a global pandemic. On the phone, you can almost feel him turning this over before filing it away as another painful oddity. “I’m cool,” he insists. “It’s just—not knowing when I’m going to trial. When I’m gonna get a chance to get out of here. That’s just kind of weird.”

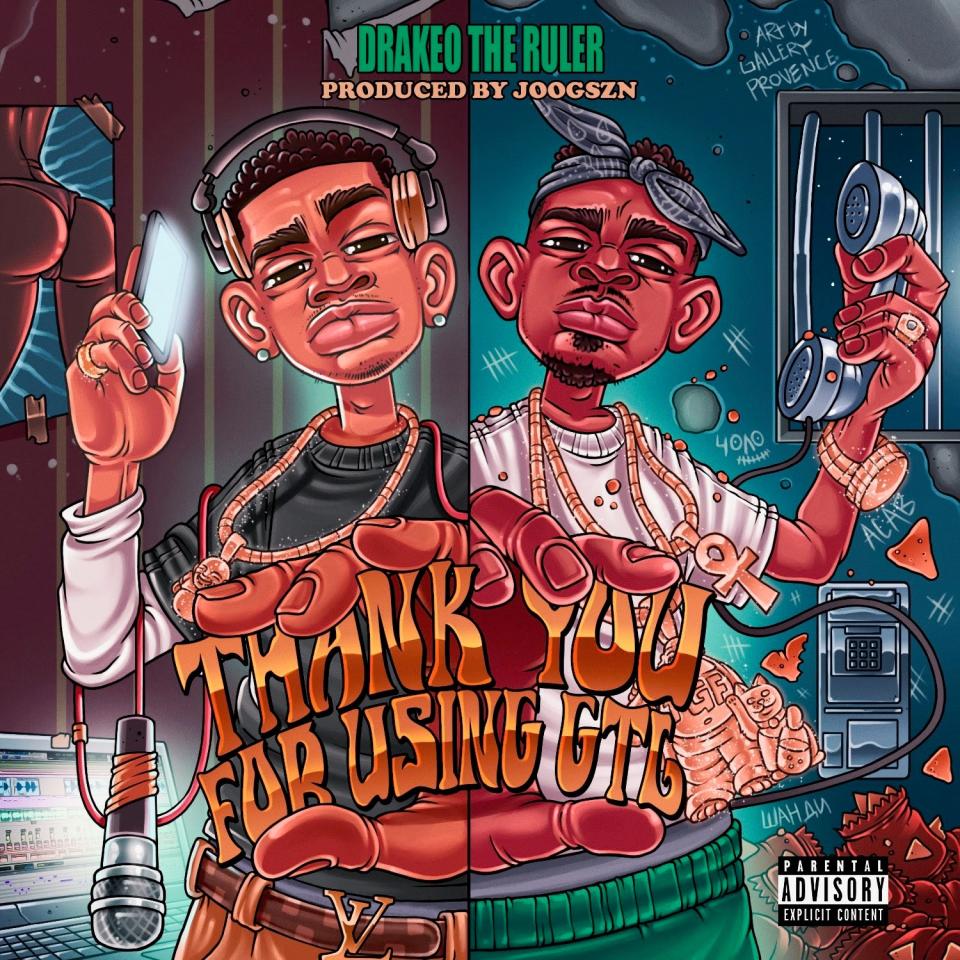

During the interminable wait for hearings he would think, “Man, I gotta do something.” He did more than something: His album Thank You for Using GTL, recorded over the phone from MCJ and released last month, is one of the best of the year. It pulls you into Drakeo’s mind: the insanities of his case, the impossibilities of his imprisonment, the joy he still holds on to. The album (and coverage of it) has also brought attention to the practices of GTL, a.k.a. Global Tel Link, a giant in the prison telecommunications industry.

In a typically fawning review, the Washington Post aptly described the strange sorcery Drakeo pulls off: “After a minute or two, the music sounds less like talk radio and more like a secret being whispered in your ear.” Over a prison phone line, Drakeo pulled off the rarest of feats: a consciousness-raising album that absolutely bangs.

On that same line, I speak to Drakeo. Every few minutes, a recorded female voice cuts in to offer a reminder: “This call is being recorded.” His producer, JoogSzn, is patched in via cell phone from elsewhere in L.A. There’s a long lineage of rappers, including Gucci Mane and Max B, who have recorded from prison, but the pair insist they didn’t take direct inspiration from anyone in particular. “I’m not the first who did it,” Drakeo says. “I’m just the person who did it the best. My shit is different than everybody else.”

It was about a commitment to his audience, Drakeo explains. “I wanted to make sure they heard every word. I wanted them to feel like I’m talking to them. I wanted them to think, ‘Okay, he going hard like this?! I can only imagine what it’s gonna be like when he’s out.’ Most people that do jail songs, they don’t wanna do all that. But if I’m gonna do it, I’m gonna do it all the way.”

The recording process was straightforward, Drakeo says: “As long as it was quiet and, shit, man, I’d just sit there,” next to the phone, “and rap. Mostly everybody knew what I was doing. And I talk low anyways.”

Joog would play the beat over the phone, along with a metronome that helped cue Drakeo in. The producer would run the audio he was getting out of the receiver straight into the recording software on his laptop. Drakeo nailed his verses over the course of a day and a half, somehow managing to stay more or less on beat. But the connection was riddled with lags. It took hours of careful postproduction with Drakeo’s engineer, Navin Upamaka, to sew it all together.

In the end, Drakeo says, the title was a no-brainer. Every call he makes, he explains, he hears that recorded female voice saying, ‘Thank you for using GTL.’ And every time he hears it he thinks, “They’re taking my money.”

Prison telecommunications is a billion-dollar industry defined by inequity: Fees vary, but at the high end, costs can be as much as $1 a minute. As the COVID-19 pandemic surged, uniquely and adversely affecting prison populations, advocates pushed the prison telecommunication companies to temporarily eliminate their predatory fees. Instead came concessions so small as to be insulting. In a dozen states, and only through April, Global Tel Link offered prisoners ten minutes of free phone time a week. In California, GTL provided two total days of free calls. At the end of June, a class action lawsuit was brought against Securus and GTL for “colluding to inflate the cost of inmate calls for a decade.”

“What helps people do well when they come home is pretty straightforward,” says Emily Galvin-Almanza, the executive director of Partners for Justice. “Access to housing, a job, support. And what sets the stage for all of those things is community connection. Being able to remain an active presence in the lives of family members. Speaking with the people you'll come home to is essential.” Global Tel Link makes maintaining that connection often prohibitively expensive. “This isn't just a one-off bad act,” Galvin-Almanza says. “It's emblematic of the larger system which is toxic and cruel and working against the interests of public safety.”

Thank You for Using GTL by Drakeo the Ruler gq july 2020.jpg

Drakeo and Joog started working on Thank You for Using GTL before the murder of George Floyd and the ensuing nationwide protests, but the album ended up a natural fit for the national mood. “People are speaking up and people are paying attention,” Drakeo says. “Timing is everything.” I point out that the title has gotten widespread attention on press platforms like this one, which aren’t traditional arenas for conversation about the sins of the prison telecommunications industry. “That’s exactly what I thought about,” he says, when he was naming the album.

Drakeo and Joog say they’d already started on a sequel but that the project is paused, in part because of the events that have occurred since GTL came out. “They only bring me out an hour a day to use the phone now,” he says. “And every police in here talks about the mixtape. ‘Oh, I heard you got an 8.5 on Pitchfork!’ Some of them be like, ‘Oh, let me stop before you put this in a song.’ They say, ‘You Drakeo the Ruler?’ I say, ‘No, I’m Archie Bunker.’ ”

He says he’s constantly worried that when the prison guards bring up the album, or his rap name, they’re not just engaging in banter but are actively trying to get him to say something that would be detrimental to his case. So, he says, “I just avoid all that shit.”

Eventually our conversation turns to the more general horrors of his time in the justice system. “You take all my friends away from me and put me in jail. You charge me with first-degree murder for something I didn’t do,” he says, summarizing. “Sounds pretty extreme. Over some rap videos? With monkey masks?” He’s referencing the video for the track “Chunky Monkey,” which was actually played in court as evidence against him. “I remember that shit like it was yesterday, dimming the lights and showing music videos. Like it’s Showtime at the Apollo.” Drakeo’s understandably fixated on the bizarre gauntlets he’s endured. At this point, due to coronavirus complications, the earliest trial proceedings will restart is September.

Before we go, we turn back to the making of GTL. Says Joog, “It was janky but it worked. The speaker was just a Beats Pill. I had the computer on a cereal box on the couch. It’s like, you know how there’s the preconceived notion that you gotta be in a studio to make good music? We had the most jankiest setup ever—and, boom, this comes out of it.”

Drakeo lets out one of his regular cackles. It’s massive. As it rolls over us, Joog continues. “These were the circumstances,” he says, “but fuck it. We said, ‘We just gonna make some hard shit.’ ”

Originally Appeared on GQ