A Double Climbing Fatality At Tahquitz Remembered

This article originally appeared on Climbing

In October 2003, a double climbing fatality occurred when Dave Kellogg and Kelly Tufo, ages 32 and 41, fell from the top of a multipitch route at Tahquitz Rock in Southern California. At the time, my editor asked if I’d do a short news piece, maybe 1000 words. I had once spent a summer in the area, and knew the cliffs somewhat.

Nearly 20 years later, a line in an upcoming story by Ed Douglas caught my attention. It was a tale I knew: In 1966 the British mountain journalist Peter Gillman had been looking through a telescope from the Swiss town of Kleine Scheidegg when John Harlin fell on the Eiger, jumaring on a rope that cut.

Ed wrote that it was “a moment that has haunted Gillman"--whom I have talked to before--”ever since.” The below is a story that has haunted me. Once I started looking into it and talking to people, and especially once I reached Florabel Victa and got a sense of her and Dave Kellogg’s life, I couldn’t stop thinking about it and taking notes. The intended news piece got longer and longer, turned into a feature, turned into a cover story, and the issue was our most widely read of the year.

One friend, a climbing writer, challenged me on it. He said, “WTF? Why did you write that? It was just a normal accident.”

That was the point. These were not hardened veterans. The great British alpinist Doug Scott once told me he accepted the possibility of death every expedition; Joe Simpson (read Touching the Void) went over his practical affairs with his partner before any trip. Dave Kellogg and Kelly Tufa, though, were normal like us.

I have spent a lot of years writing about climbing, and they have made me more aware of the echoing effects of loss. Kelly Tufa left behind loving parents--who took in the dog that was his constant companion ("Tell everyone Squiggy is OK, he's with us," the father said on the phone)--and a relationship he was really excited about. His girlfriend, Karissa McQuaid, said he was "wonderful" with her two young sons, whom she shushed in gentle tones in the background. Dave Kellogg had wanted to get home that evening in time to put Nicolas, age 2, to bed. The other day I emailed Florabel, letting her know the article might be re posted. Nicolas has grown up. He is 6 feet tall and soon to turn 21.

This article was published in Rock and Ice, now merged with Climbing, in March 2004.

Dave Kellogg spent Saturday, October 18, in prized company--with his 2-year-old son, Nicolas. The next day he was off for a last route before winter hit Tahquitz Rock, above Idyllwild, California.

The plan was unusual only in that Nicolas' mother, Florabel Victa, whom Kellogg lived with and always called "my wife," and Nicolas weren't coming. Usually the three spent weekends together, in Joshua Tree or Red Rocks, Nevada.

Victa was a constant companion on such trips, not a climber but an ardent camper and participant. "I love to watch him climb," she says. "I just love it." The couple once went on a three-month climbing trip to Asia, and took the year 2000 off from work and spent most of it in Joshua Tree, returning home to San Diego once a week to check mail, then driving back out the same night.

Kellogg, age 32, had been climbing 13 years, and formerly climbed every weekend (in college he'd drive 12 hours to do so). After Nicolas was born, Kellogg would only go out for the day on multi-pitch routes, the only time the family stayed home.

This Saturday, Victa had plans with a friend; so Dave and Nicolas hung out: played disc golf, got cheeseburgers at McDonald's, rode elevators. "Nicolas"--Victa laughs, the deep laugh that is her second nature--"is into elevators." Dave and Nicolas rode the parking-lot elevators at the Fashion Valley Mall, and went inside and rode the glass elevators, too.

Kellogg ate dinner at home that evening, and left at 9:25 p.m. for the two-hour drive to his friend Kelly Tufo's house in Anza, half an hour from Idyllwild. The two intended to reattempt The Step (5.10a), a 500-foot trad route at Tahquitz. They had backed down from the crux second pitch the previous Sunday.

Victa, 44, walked Kellogg out to the garage, and recalls him saying, "I'm a little nervous."

"Don't worry, you'll send it," she said.

"I know. I'll call you on my way home."

He did not come home. Two weeks later, Victa would run an errand in Fashion Valley, with Nicolas in the car. As soon as she turned into the lot, he shouted, "Papa! Elevator!"

***

Eight weeks before, Kelly Tufo, age 41, had complained to his onetime housemate Barnett English that he would never "in a million years" find a girlfriend in tiny, rural Anza. The very next day Tufo met Karissa McQuaid, 28. She lived right down the road.

The relationship took off, and the two were together every day the week before Tufo's second attempt on The Step. Tufo, she says, was wonderful with her two young sons. McQuaid joined in Tufo's plans to sell his house and move to Joshua Tree; she, too, put her house on the market.

Of that last Saturday, she says, "Oh, my gosh, that day was so good." They went to a swap meet, where she bought veggies for homemade salsa and he found a screaming deal on a power tool. They finished a job painting a friend's house, then came back to Tufo's, where he showered, put on a clean shirt, and served tortellini by candlelight.

Kellogg arrived later to stay over, and the next morning when he entered the kitchen Tufo said, "Karissa's giving us some good energy to get to the top."

The trio watched part of a climbing video Kellogg had brought; it was still playing when the men left.

"They were all stoked," says McQuaid, "running to the truck all smiles. I can still see their faces."

Tufo sat in the passenger seat of Kellogg's GMC truck, unusual for him. He normally preferred to drive his own vehicle rather than ride. "He had this thing about falling," recalls McQuaid. "Even riding in a passenger seat of a car, he could get a falling sensation. One of the few people he trusted to drive him around was Dave."

They pulled out of the driveway at 9 a.m.

***

Tahquitz and Suicide Rocks are imposing granite cliffs on the hillsides above the artsy resort town of Idyllwild, about 100 miles east of Los Angeles in the San Bernardino Mountains. Tahquitz is the higher peak at about 8,000 feet, with routes up to 800 feet and a steep 45-minute approach. One of the first technical climbing areas developed in North America, it offers classic routes up to seven pitches on cracks, friction slabs and flakes. Art Johnson and Bob Brinton originally climbed the 500-foot Trough (5.3) in 1936, and the decimal rating system was developed here for a 1956 guide book.

Tahquitz is a traditional crag and a serious one. Established routes tend to be clean, but the crag is subject to periodic rockfall. Rock quality deteriorates on the mid to upper pitches of the wall, and belays can be elusive. Many a leader has passed a decent stance only to come to the end of the rope in the middle of nothing.

"It's nebulous ground, up there, criss-crossing ramps," says John Long, who put up Le Toit (5.12a) next to The Step. "These are nothing like Yosemite routes, it's not a nut-friendly crag. The cracks don't tend to be deep, and other than that you get flakes and blocks, although you need to wonder about the blocks." Plenty of people have gotten lost and benighted up top.

***

The road through Idyllwild ends in the Humber Park trailhead, where at 9:30 Tufo and Kellogg saw their friends Jeff Engel and Karen Biggs. Kellogg and Tufo said they were off to The Step, one of Engel's favorites. The first pitch is easy, the second the crux, with a burly layback and mantel onto a ledge. Engel cautioned them about the third pitch, which, although only 5.7, is funky climbing and hard to protect. The final pitch takes a slippery 5.7 slab. Engel also warned them of reports of rockfall on the route, and confirmed a plan to climb in Las Vegas with Kellogg the next weekend.

Engel asked his friends to join him and Biggs later at a Mexican restaurant. "Dave said no," says Engel, "he would probably head straight home to help put Nicolas to bed."

Kellogg and Tufo set off on the trail to Lunch Rock, where climbers stash their packs, and scrambled to the base of their route.

As the stronger climber, Kellogg was to lead the crux, with Tufo capable of following the route and leading less difficult pitches. The two put on their helmets, and started up The Step at about 11 a.m.

Dave Kellogg, exuberant and outgoing, was a buyer for Biofite, an R-and-D firm for medical diagnostics. On Halloween he'd dress up and go trick-or-treating at all the campsites in Joshua Tree. "He's just really friendly," says Victa, who speaks in an argot blending past and present. "He talks to everybody, says hi to everybody, asks, 'What are you climbing?' People gravitated to him. People remembered us," she says honestly, "because we were always laughing."

Kellogg went out of his way to help people. Friends remember a vacation in Costa Rica three years ago, when, after midnight and with a plane to catch in the morning, Kellogg drove a stranger with an injured leg an hour to a hospital. "He would say yes to everyone," says Victa.

Each November Kellogg held a climbathon, for fun, at Joshua Tree, inviting a gang of friends. He'd assign points for routes, and give out prizes: movie tickets, calendars, Nalgene bottles, Clif Bars, often booty he had earned at climbers' clean-ups.

Kellogg was known for climbing safely: "He was always the one double, triple, quadruple checking his gear, knots, everything," Bill Sukula, a friend, would later post on a www.rockclimbing.com thread that grew into an epic poem of sorrow, recollection and concerned suggestion. By late November [2003], when the thread ended, it had received 200 postings and 48,000 views.

Kelly Tufo was a carpenter and licensed contractor. Friends say he was happy-go-lucky, curious, gentle and always had his dog Squiggy by his side.

"Of all the people I know he's the most giving and selfless," says Barnett English, who owns a coffee business for which Tufo built kiosks. "He would do things for me when he had a hundred things on his plate and not charge me. Even if it took all night he'd just do it."

Tufo was funny, a performer: He would go into a Marty Feldman routine and stay in character for three hours. He read widely and often quoted from favorite books; was keen on NPR and the History Channel; and was a World War II buff. Lisa Hernandez, a friend, says that whenever he met an older man, he always asked if he was a veteran. "If the man said yes, Kelly first made sure to thank him and then asked about his war experiences."

"He was safety this, safety that," says English. "He'd been in construction all his life and he still had all his digits."

***

Around 1:30 P.M., Meg O'Neill and Art Morimitsu were on the third pitch of a linkup of Human Fright (5.10a) and Angel's Fright (5.5), 150 to 200 yards from The Step, when they heard a roar.

O'Neill saw rock coming down near The Step. Morimitsu, on lead above her, said, "I hate that sound."

"It roared like an avalanche," says O'Neill, "plus there was a scraping, a clitter-clatter."

She looked more closely: "I saw a large object falling, I remember thinking it was a backpack, but it was a backpack wearing a helmet. I could see rope, and then a second thing fell." Two men appeared to tumble down the buttress near Fool's Rush, just left of The Step, then bumped onto steeper terrain and free-fell for 150 or 200 feet, landing at the base of Fool's Rush.

"I remember seeing helmets, a pair of shoes and a rope. When I see it in my head I see it's people, and one of them is broken."

O'Neill managed to say, "People are falling," and Morimitsu glimpsed the second figure, Kellogg, his arms waving.

The two men disappeared into trees in a gully.

She started shouting, "Are you OK? Can you let me know if you can hear me?

"I stopped and listened, and I got nothing."

***

Adam Baroumand, 26, of Irvine, a climber of 10 years, had just come up the trail. It was his first time at Tahquitz.

Within a minute of reaching Lunch Rock he heard "metallic jingling, that sound of a rack when someone falls ... Then three pops, could have been more--they were cracking-like-thunder pops, really quick.

"Then this grunt, 'Waaahgh!' It was such a horrible sound, it comes in my head every now and then.

"It was, like, after the anchor failed ... when he knew." There is a long, long silence before Baroumand can speak.

"Two or three seconds after that I heard both the bodies land in softer-sounding thuds, and rock fall."

"Now that I think about it, they were way up there. I think it was over 300, maybe 400 feet."

Baroumand fumbled in his pack for his cell phone, then thought, "Screw it!" and raced upward.

"Is anyone at the base?" O'Neill was shouting. She directed Baroumand to Dave Kellogg's location; not knowing his name, she just kept shouting, as others appeared, "Guy in the yellow backpack, go that way!"

***

Says Baroumand, "I just kept going up and up and up, toward the left, up the third class [section]." After five or 10 minutes, "I got to a ledge, and he was just right there, with lots of loose rock everywhere."

Kellogg lay on his back, facing upward, his left eye partially open. The rope was tangled in nearby trees, pulled taut across his right arm and shoulder.

"He was somewhat responsive, in major shock," says Baroumand, who knelt, then stood briefly to shout for someone to call 911. He told Kellogg help was on the way, and unclipped Kellogg's tube-style belay device, rigged with a bight of rope, from his harness to ease the tension. "He was kind of grunting with me."

At 1:49 p.m., Baroumand's partner Helene Herron reached 911 on her cell phone. A soloist, Tom Hartger, had appeared and was blowing his whistle, prompting someone near the trailhead to call the sheriff.

Kellogg's helmet was broken, half of it nearby in the branches. He had a head injury and a large gash to the knee. His neck was bent to the side.

Baroumand patted Kellogg's shin and said softly, "It's OK, it's OK."

He said, many times, "Stay with me." Kellogg would respond with a moan.

At around 2:10 a small silver helicopter came over the summit, quickly buzzed the area, and left.

Baroumand unbuckled Kellogg's harness. He remembers seeing three cams on three separate locking biners equalized on a yellow cordelette. A gray cordelette was tied from Kellogg's belay loop into the yellow cordelette. Baroumand recalls seeing two, 1-inch camming devices, and one 1.5-inch cam, which he unclipped from the cordelette and set down.

Kellogg was semi-conscious for 20 minutes, insensible for another 40.

"Once I nudged Dave and said, 'Hey, wake up.' It was just something else to say."

Finally, Kellogg stopped breathing.

"In a way I felt like I had to do the textbook thing," recalls Baroumand, "telling him to hang in there. Now when I look back, I wonder if I should have ... spiritually consoled him, said, 'It's OK, man, you're just getting there before we do'--that's what I wanted to say." He pauses again. "It's something that I struggle with."

Another climber, Ryan (last name unavailable), reached Tufo, who was about 30 feet away, five minutes after Kellogg died. Tufo had landed in a big crack. He had a head injury. Ryan touched his arm, but he was lifeless.

***

A helicopter from the California Department of Forestry arrived close to 3 p.m. and hovered above the base. Hartger phoned the sheriff to say the rescue had become a recovery. The helicopter left.

Meg O'Neill had earlier fetched a stashed Stokes litter, and gone through the men's packs, finding Kellogg's ID. The climbers positioned the litter and packs as markers for finding the climbers, and finally left. Hiking up the hill were 18 men--including a doctor--from the Riverside Mountain Rescue Unit (RMRU).

***

Kelly Tufo and Dave Kellogg's accident stunned their peers: How could it have happened? In the three weeks it took for RMRU, a volunteer organization, to examine the equipment and accident area, and release a report, speculation and theory abounded.

Judging from the gear clipped to Kellogg, climbers initially felt that Tufo must have zippered pro and fallen directly onto an anchor. A very likely site was the third pitch, a flake chimney, too wide for much good pro.

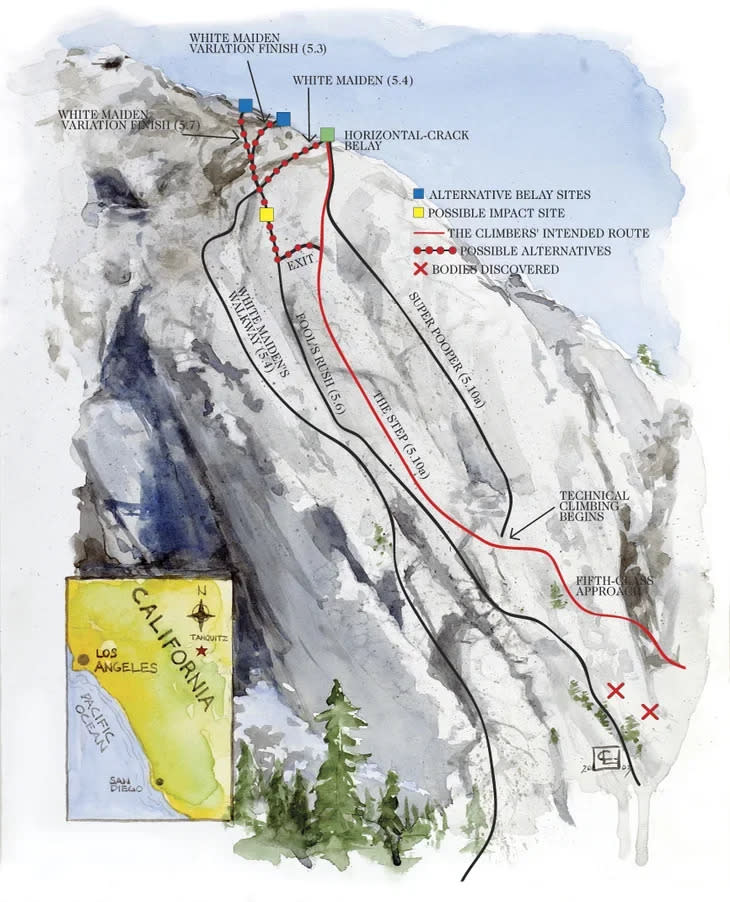

Then word circulated, unofficially, that the fall had been from the cliff top, and with no gear on the rope between the climbers. Jeff Engel carefully considered the fourth pitch (5.7), shared by Super Pooper. He and Kellogg had done that pitch together in summer 2002 to finish Super Pooper, which comes in from the right; another route, White Maiden's Walkway (5.4), joins Super Pooper/The Step up high from the left. About 40 feet below the top of Super Pooper/The Step is a headwall, climbed by a 10-foot crack to its right, then a 30-foot runout to the belay. All three top pitches finish at a belay at a horizontal crack off to the right, in a 10-foot flat area below the summit blocks.

Engel's proposed scenario involved a seconding fall--an unexpected turn since such falls are normally not very forceful, especially on a slab. Yet on this pitch a second could swing 10 feet rightward into space from two tricky places: the headwall or the delicate friction moves just above it. Tufo, following, could have fallen, shock-loading the belay, possibly wrenching it sideways. Or he might have come off near the top of the pitch, moving a little too fast on easy ground for the belayer, creating a loop of slack.

The scenario seemed consistent with the 30 feet of rope between the men, the gear Tufo carried, and the anchor cams, which were the right size for the horizontal crack. Engel felt Kellogg would have belayed at that spot, as they had before, but the crack is shallow, flaring. "You have to work to get cams in there," he says, "and it can even happen that they look good but they aren't."

On November 8, the RMRU released its report, which suggested an entirely different scenario. Some RMRU members had hiked to the top of Tahquitz, lowered colleagues down, and examined The Step and nearby routes. "We covered a large area and didn't discover any broken flakes," read the report. "Yet, we did find the first impact site, which was about 60 feet from the top. A team member then lined himself up with the fall line down to the first impact site. There we found what looked like skid marks in the lichen and they lined up perfectly with the first impact site. We believe that the climbers finished The Step and traverse[d] over to the top of the White Maiden. Since the last section is easy we think they may have been walking up to the top when one slipped and fell, taking the other." The skid marks were described only as being "high up."

"The only damaged pro," the report read, "was one cam of a small camming unit. "It looked as though it had been twisted and the one cam didn't work correctly. We wonder if it may have been damaged in the fall?"

The report never claimed finality. "Again, this is what we believe may have happened, but the two that really know are no longer with us."

***

What didn't seem to jibe with the analysis was that Kellogg had the rope through his belay device--and who would walk with cams and a cordelette dangling around his legs?

Engel considered the report scenario possible if the two finished The Step, and Tufo sat for a moment beside his friend at the flat belay. Kellogg might have removed the anchors so they could walk around the block to flat ground, where they'd sort gear and coil the rope. Maybe one person stumbled here, unusual as that would seem, and rolled.

Belay failure still seemed most logical. Engel looked at the gear when it was returned to Victa, though by then no longer in its original configuration. The three cams noted by Baroumand on the cordelette (and while Baroumand later questioned his memory of all three, he was positive of the 1-inch and 1.5 and the three locking biners) appeared to indicate a belay pulling. One of the 1-inch units was a U-stem, both wires badly twisted. The other, single-stemmed, looked fairly intact, yet a cam was stuck. The 1.5-inch cam was slightly twisted. Certainly it could have been crunched in the fall, but most of the other gear on the harnesses was not. Engel also found three or four shallow, hardened melt marks on the cordelette.

The idea of Tufo falling and Kellogg's belay pulling is supported by the pops heard by Baroumand: "I think that sound was each piece of the anchor pulling," he says. "Each piece sounded distinct."

Rock might even have broken at the belay. Possibly, though, the rockfall was clothes-lined off during the fall.

November 14 brought a final turn, when the RMRU released a photo showing the location of the skid marks and impact site. The diagram was somewhat ambiguous, and the RMRU did not respond to requests to pinpoint the sites, but the skid marks appeared to be 40 or 50 feet left of the horizontal-crack belay, near the top of White Maiden or one of its two variation finishes. The impact stain was below, near Fool's Rush.

It seems unexpected for the pair to take the long traverse needed to reach the start of the last pitch of White Maiden. Still, maybe the climbers did veer off The Step atop the third pitch. Kellogg could have led sideways to Fool's Rush, which reaches the top of White Maiden and both its variation finishes. The left of the two White Maiden variation finishes is 5.7, the right 5.3.

Meg O'Neill's report of the bodies striking the face near Fool's Rush and then free-falling suggests the climbers were farther left than the horizontal-crack belay at the top of The Step. Also, the placements of the skid marks and impact point suggest that they were on one of the two White Maiden variation finishes. Both lines (particularly the right-hand one), cut right at the top, and a swinging fall could help account for the men's trajectory in that direction.

Judging by the gear each carried, Kellogg may have just led, probably a final pitch to a stance just below easy ground. Perhaps Tufo, seconding, fell below the belay, or while leading past it on a quick scramble to the top; maybe a hold broke. Kellogg would have struggled, digging in his feet, to hold the fall.

A rescuer, Glenn Henderson, found a "small cam," possibly a 2-inch unit shown in Baroumand's photos as being with Kellogg, undamaged and attached to a carabiner, lying in a tree near Kellogg; he found half a nut tool by Kellogg's body, the other half on a ledge. Neither held a cord or carabiner, and Tufo had his own nut tool clipped to his harness. Maybe Kellogg was breaking down the belay when something happened.

Likely, unlikely. ... The whole series of events was unlikely.

No one tried harder to figure out the details than Engel, but in the end even he accepts an element of mystery. "We'd assumed that only exceptional circumstances, such as a fall onto the belay, could explain such a catastrophe to safe climbers. The surprise was that there could be a much simpler possibility in a stumble at the top," says Engel. "That's the lesson."

To Florabel Victa, the chain is fairly clear. She says softly, voice near singsong in rue. "They"--she pauses--"fell."

Alison Osius is senior editor of Climbing. This article was originally published under the title “Darkness at Noon.”

See this later analysis by the American Alpine Club.

For exclusive access to all of our fitness, gear, adventure, and travel stories, plus discounts on trips, events, and gear, sign up for Outside+ today.