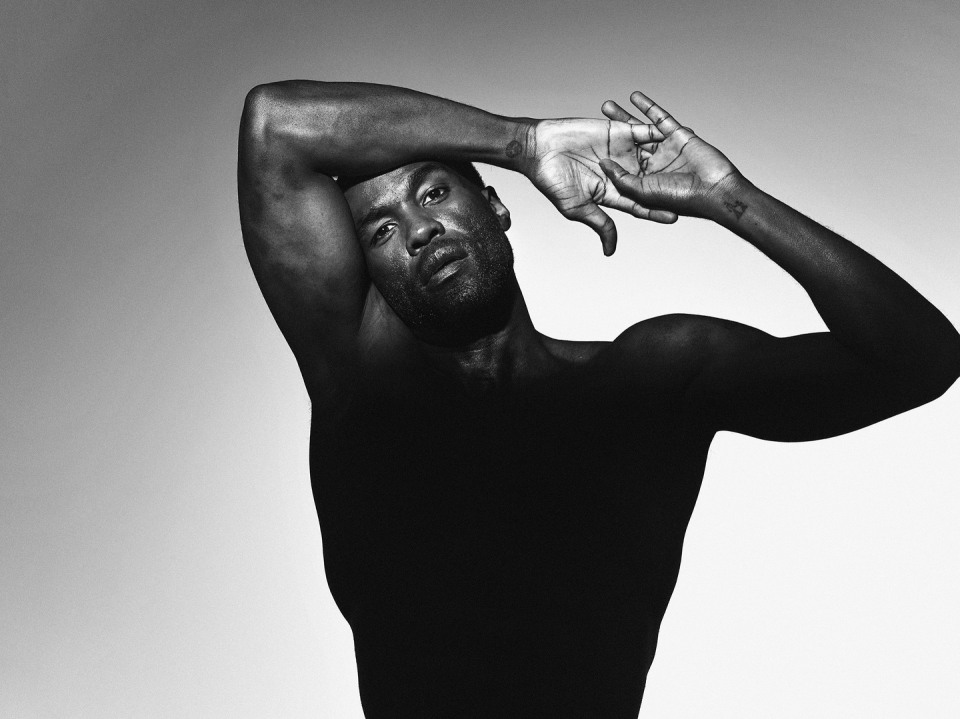

'Don't Feel Guilty for Laughing and Feeling Joy'

IT’S LATE MAY, and I’m sitting in an Airbnb in Culver City, California. I’m in the mirror, attempting to make a Candyman-themed video for the #WipeItDown challenge, but I can’t seem to get the timing right. It’s strange and frustrating, because I’m usually pretty good with technology. After what has to be about 20 tries, I sit down on the couch to compose myself. There’s no television in the house, so I’m just looking. Staring at the empty fireplace. It’s more than three months into my COVID-induced isolation. I’m lonely and I’m stressed, but I don’t want to admit it. And then I hear the horns.

The house I’d rented has a plaque that deems it a historic Hollywood landmark. It sits on a quiet row of other historic homes directly across the street from the Culver City police station. It was quiet inside, but when I heard the cars honking their horns in the distance, my entire body froze. I hushed my breathing to ensure absolute silence. I wanted to be sure I wasn’t making this up in my head. A few days prior, George Floyd was murdered at the hands of the Minneapolis Police Department, and after seeing the murder play out, the officer kneeling on Big Floyd’s neck for eight minutes, 46 seconds, it felt like the entire country was upside down. The horns I heard signaled that there was a protest near. My breathing picked up again, but this time faster. The next thing I remember, I was out on the street, walking toward the sounds of the horns. Coincidentally, I was dressed in all black, my wardrobe of choice for the Candyman video. I took it as serendipity.

I remember being so angry. I was aware that I was a six-foot-three Black man dressed in black sweats, a black hoodie, and a black protective mask over my face. I didn’t care, and as I walked past the police station toward the horns, I remember a spirit of defiance rising to equal the anger I was feeling. I got around the corner to where the horns should have been. Instead of finding hundreds of likewise angry citizens, calling out for justice, and drivers honking their horns in defiant agreement, to my frustration I found absolutely nothing. I was confused. I walked back to my little historic cottage, disappointed, and found myself on the couch staring at the fireplace once again.

And then the same damn horns. Coming from the same place. This time I immediately got up and walked in the direction of the sound. It took me to the gate at the back of the police station. I looked at the camera, and for the first time I considered that I might look suspicious. The sound was coming from the opposite side of the building. I took the same walk, following the horns, and once again I found nothing. My walk back was slower this time. My breathing was more methodical. I calmly began to punch my fist into my open palm. I realized that I was experiencing rage.

Being a Black man in America means one has to learn to hoard as many resources as possible for survival. In the story of that one afternoon in Culver City, I experienced feeling loneliness, depression, frustration with systemic oppression, anxiety about expressing anger in a Black body, helplessness.

The next day, I invited a couple friends over for a small barbecue. We talked about how it’s impossible to quantify an appropriate response to watching someone be killed in such an inhumane and nonchalant manner. And we talked about rage.

Growing up, I always lived in a Black neighborhood. From the Magnolia Projects to my neighborhood in West Oakland, I was always surrounded by Black folk. It’s where I learned community, Black love, Black pride. Although I wasn’t immune to racism, I didn’t interact with it much in the places called home.

One of the first times I remember experiencing any kind of victimization centered on my Blackness was during my freshman year at Berkeley. I studied architecture, and for architecture students, it was common to spend the whole night working in the studio. One night, I left the studio around 1:00 a.m. to go to my dorm and get something to eat, and then I headed back to the studio to keep working. As I approached the building, there was a woman going inside, just a couple steps ahead of me, and I thought, Okay, I’m just going to have her let me in. She must have felt me walking behind her, because she began to hurry. She made it to the door, and as she was going to close it behind her, I tried to go in after her. She turned around and pulled on the door and wouldn’t let me in. She said, “Stop, you don’t belong here.” I said, “What are you talking about? I’m going to the studio. I’m going to the same place as you.” And she said, “Please stop. You don’t belong here.”

As we stood on either side of the door, still slightly open, I went to pull out my ID—to say, Look, I’m a student, too. She said, “I’m gonna call the police and tell them that you’re trying to rape me.” I pulled the door open, and she began running and screaming at the top of her lungs, “Help! Help! He’s trying to rape me!” It’s 1:00 a.m., and I’m trying to get her to be quiet, but she’s still screaming, so I just stopped and let her walk. I knew there was no rationalizing with this person. Two minutes later, I walked up to the studio and sat down at a computer. I saw her across the room, but she wouldn’t make eye contact.

The campus police came in, because she called them. They asked her to step out to talk, and then they called me out to ask what happened. They apologized and left. What more could they do? I went back to my computer to work, and I remember being so angry that I cried. It was frustrating. I deserved to be there. Period. That was my reminder that even if I did everything right—played the game by the book—some things in life would be unavoidable. Because I was Black.

I was 18 years old. I did the only thing I knew to do. I cried, and I swallowed that shit.

DURING THE GATHERING WITH FRIENDS, WE TALKED ABOUT EDUCATING ONESELF.

MY DAD WAS always reading when I was little. Newspapers. The Koran. The Bible. Books that he got at the flea market. Books on health. He didn’t trust anything. He was born in 1945 in New Orleans, and as a Black man, he knew that he couldn’t leave it up to America to tell him the truth about his body or his mind or the way things were. His father was born in 1886 in the West Indies, and he lived in fear of his children being taken back there if anyone found out that he was an immigrant. For both of them, there was a general mistrust of authority.

Black men—Black people in general—don’t have a reason to trust America. History will tell you that, at the end of the day, we’re going to be the first ones to be manipulated and systematically taken advantage of. And my father knew that, so he lived in a constant state of education and preparation. Whenever he received information, he would always do his own research before he chose to believe it or not. He knew that education and information were the only ways he could control his destiny.

Today, when I want to know what’s going on, I watch CNN, I watch Fox News for entertainment, I read the usual papers. But when I really want to know what’s happening in the world, I talk to my friends who work in politics, in education, in business or medicine, and I try to shut up and listen. Just a couple weeks ago, I asked a friend of mine, one of my fraternity brothers from Berkeley who’s now a professor of African-American studies at Harvard, to give me a list of books that I should be reading right now. He gave me a list of probably 30 books to get. I narrowed it down to ten. So that’s how I teach myself now: I lean on my community to share resources, educate me, and help me grow—to make my world bigger.

WE TALKED ABOUT THERAPY.

MY MOTHER IS Christian and grew up with the same view of therapy that a lot of other Black Christians from the South held—prayer was the answer to everything. My father would have been suspicious of therapy because he didn’t want to talk to other people about his business. To me, therapy meant lying down on a couch and having someone psychoanalyze me and confuse me, and I rejected it for a long time.

Then I went to drama school at Yale, which was an introduction to asking questions about what’s happening deep inside oneself. That was the softening of the armor that opened me up to the idea of therapy, and it was also the first time that I was around other people—Black people—who went to therapy. There’s a stigma around mental health in the Black community, particularly with men, that means we don’t talk about how we’re feeling, and it was strange to be around Black people who openly discussed seeing a therapist.

It wasn’t until 2019 that I finally motivated myself to go. I found a Black therapist, a woman, and within three minutes, I’m telling her everything. I’m comfortable, because she can relate. I trust her. She’s Black. We speak the same language. (With my therapist, I wanted to be able to talk about being Black. I wanted to be able to use my vernacular. I didn’t want to have to explain what it felt like to have someone follow me around the store. I just wanted to talk about the fact that it happened and have that person understand.) Eventually I left therapy with a better sense of self.

Then I began telling everybody else about it: “Man, I started doing therapy, and it changed my life!” It changed the way that I believed in myself, the way that I began to move through the world. I had a completely new understanding of what therapy could be, and as I’d talk to my friends about it, they would say, “Yeah, I’ve been thinking about therapy, too.” There was this collective curiosity that I didn’t even know was there. Historic disenfranchisement kept those resources out of reach to the point that many believed that our rejection of therapy was primarily cultural. I’m glad to see this narrative changing. We’ve got a lot of internal healing to do in this world, and therapy is going to be a big part of that. With the right relationship, therapy can be a safe space where we can be heard and seen in a world that too often chooses not to hear or see us.

WE DISCUSSED HOW EVERYONE HAS THEIR DIFFERENT ROLES TO PLAY.

MIY LIFE IS hardly without struggle, but I guess when I was a kid, love kept things hidden that needed to stay in the dark. Because my parents insulated us with love, I’ve been blessed with a naivete—some might call it confidence—that allows me to think that I can do anything I want. I got into Berkeley. I got into Yale. I had a job before I graduated. I went straight from The Get Down to my next job. And then I got Aquaman and The Greatest Showman. I had the fortune of following my appetite.

In the beginning, the question before taking a job was What experience do I want to have? Now I’m in a place where I’m asking myself, What is the responsibility that I have, given the platform that I’ve been blessed with? With Watchmen, I saw how important it was for other people to see Dr. Manhattan embodied in a Black man—to see that story about Black love between a god and a Black woman. I revisited the theme of intergenerational trauma and trauma inherited from our grandparents, and I entered into that conversation online with fans of the show.

With Candyman, I knew that no matter when you’re making a movie about Black men being murdered by police, or the history of lynching, you can bet that conversation will be relevant in the zeitgeist. Especially if you’re making that movie in America. Of course, when we were making the movie last year, we had no idea the extent to which our message would resonate in the moment. But the moment is here, and I’m happy to have the art to accompany it.

The Trial of the Chicago 7 wasn’t something that I pursued specifically, but the opportunity to play Bobby Seale? You don’t grow up in Oakland without knowing about the Black Panthers— or knowing about Bobby Seale—and I knew that I wanted to tear into that role. I found a clip online where he talks about being in “the hole” and not letting his oppressor see him broken. I learned about resilience from him, and about rising above the tools of oppression and sharpening your mind and body in order to withstand the fire. To me, The Trial of the Chicago 7 is about finding your act of resistance. Fifty-plus years later, the events of the film resonate louder than in any time since. I look across the country and I see young people being loud and causing a disruption and making their voices heard. It’s inspiring.

Right now I’m in Germany for five months—I’m here filming The Matrix 4, and The Matrix is dope. It’s great to be gainfully employed and to know that I can walk into any room and hold my own. But back in America, we need soldiers on the front lines marching. We need warriors willing to uphold the promise of “No Justice, No Peace.” We need people like myself with a platform to continue to speak out and to be standing and doing the right thing. And so sometimes I question whether or not I’m doing the right thing by being away from America right now. I donate my money, my time. I use my platform to amplify others’ voices, and sometimes that feels like it isn’t enough. I want to be on the ground. The people I love, my family, my close friends, the Black women in my life—they tell me to be kind to myself, to stay informed, and to stay ready. So that’s what I try to do for now.

As we sat in the backyard, talking through the state of the world, my friends and I would also make jokes about someone’s old shoes, or the fact that someone was being long-winded, or dating missteps. We acknowledged that while anger is a part of the contract of Blackness in America, brotherhood and community are nonnegotiable terms. I never posted the Candyman video, and I don’t believe I will. The timing was never right. The post I made was a simple one, but it felt relevant to the betterment of our health. It was a message that said, Black Family, don’t feel guilty for laughing and feeling joy today. We need that too.

You Might Also Like