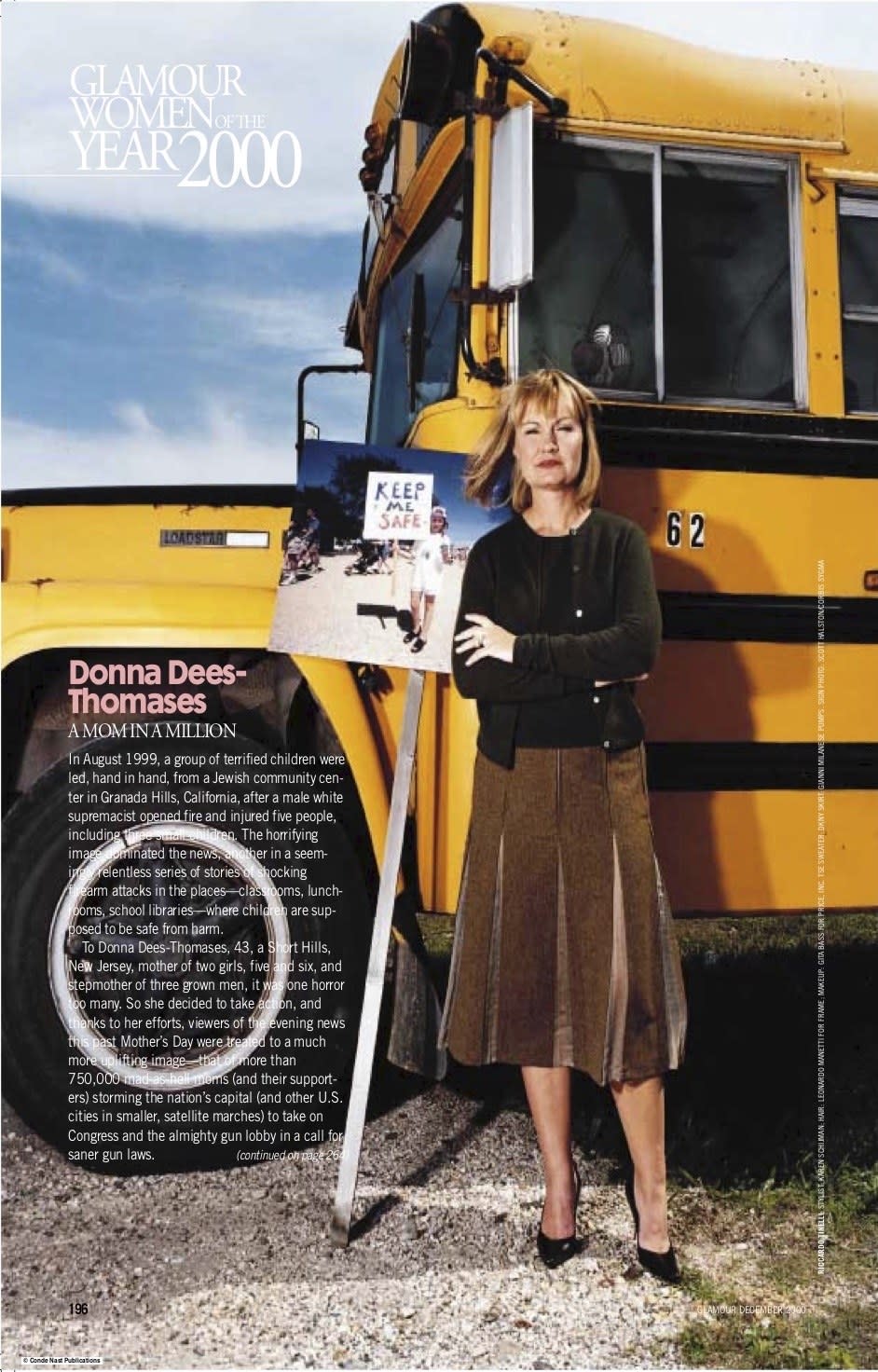

Donna Dees-Thomases, Glamour ’s 2000 Woman of the Year, Says Moms Are Necessary for Movements

In 2000, Donna Dees-Thomases celebrated Mother’s Day by going for a walk.

About 1 million people joined her.

It was the Million Mom March, a giant grassroots mobilization of moms against gun violence that Dees-Thomases had organized over the course of just 10 months. A mother of two girls living in suburban New Jersey, she had watched the Columbine massacre open up a summer of violence that ended with an attack on a day camp at a Jewish Community Center outside of L.A. in August of 1999 that left one dead and five injured. The sight of terrified children fleeing a gunman shocked her into action.

At this point in the story, which Dees-Thomases is telling me from the backyard of her home in Louisiana, she interrupts herself to pet a dog that has wandered into her yard. I hear panting in the background, as she begins to talk again about governmental inaction in the face of gun violence. Then she adds, ecstatically, ”Two goldendoodles! Beautiful.”

It’s this kind of extreme, almost comic friendliness that helped her organize a historic event and launch a national movement—and the reason Glamour honored her in 2000 as a Woman of the Year.

Dees-Thomases spent 10 feverish months working part-time as a publicist for Late Show With David Letterman, parenting, and organizing the Million Moms March. In the days before social media, before smartphones, before virality, Dees-Thomases used every connection she had ever made and worked every hour she could stay awake. As her plan, which had started as bullet points on scratch paper, grew into a national news event, she promoted it by debating the head of the National Rifle Organization on Meet the Press and securing a spot on Oprah. She wore denim overalls most of the time. On the day of the march, she was so tired she nearly put on mismatched sneakers. The day was a smash success, and honors, including Glamour’s Woman of the Year award, followed.

And then? You know what happened, even if you don’t know Dees-Thomases's story. The Million Moms March was a massive success. But the mass shootings of the Columbine era continued. Innocent people died. Children died, all the time. There was no runaway movement that defeated the gun lobby and changed federal regulations and took over state houses. In 2019 there were more mass shootings than days in the year.

“Grassroots, progressive causes are not easy,” says Dees-Thomases, who is remarkably open about her own shortcomings. “We struggled so much to create an organization out of it. We attempted two mergers after the march, we struggled as an organization, we had branding issues. I think we overused our database for fund-raising.” She shares these lessons with the leaders of the other organizations she supports (and thinks you should support too): Moms Demand Action, Brady Chapter, the Coalition to Stop Gun Violence, Giffords, and March for Our Lives.

“Twenty years later I’m beating myself up a little less, because I’ve watched groups like the Women’s March struggle,” she says. “It’s difficult when you go from a Facebook page to activists across the country.” And gun-violence work, in particular, is hard (“No one wants to have a movement created by trauma and death”). She believes—she knows—that grassroots organizing to change law and life is possible and necessary. “Million Moms March was a grassroots group of women, many of whom had never organized so much as a carpool before,” she says. “But they found inner strength, used their talents and their ability to stand up to the gun lobby, and say, ‘This is what we’re doing.’”

That’s the nonnegotiable thing: women. “Men can’t organize a trip to the men’s room, much less organize a march or a movement,” she says, adding, “I do have to tip my hat to the men who support the women who are doing this work!” (Michael Bloomberg and Elizabeth Warren have the strongest gun-violence prevention platforms, she thinks.) She started organizing in 1999 because she thought there was no movement for gun-violence prevention. But that wasn’t true, she said. “There was a movement, mostly of women, unsung heroes who never had their stories told, and they had their successes coopted by mostly male-run organizations in D.C.”

After the March, Dees-Thomases kept organizing, suffering a huge setback in 2004, when Congress failed to renew the expired Federal Assault Weapons Ban. In 2012, after Sandy Hook, she said she got 1,200 emails within a few hours of the shootings, and worked to mobilize the volunteers (“If you don’t catch people in the first 48 hours of their outrage, they move on”). Starting in 2016, for three years, she organized Concert Across America, a community-based, coast-to-coast project to stop violence through music. "Oh my God, they’re so cute!" she exclaims, distracted from the topic at hand suddenly. Donna Dees-Thomases has found another dog.

“I feel optimistic,” she says. She sees progress everywhere. “Every candidate has realized there are stakeholders in this election who care about this issue who are registering voters,” she says. People don’t realize that the Virginia Tech families have been slowly reshaping gun-violence laws in their state since 2007 (“13 years, slugging along, being in the state where the NRA is based, and finally seeing progress”). The women who first came together at the Million Moms March have kept up the work over the last 20 years, even if you haven’t seen them on Oprah—Johnnymae Robinson, a Million Moms Marcher, emailed her last week because she was just named to Mayor Bill DeBlasio’s Gun Violence Survivor Advisory Counsel. Eileen Filler-Corn, a Million Moms Marcher, just became the first female Speaker in the Virginia House of Delegates. (“And they just spearheaded seven gun-violence prevention bills through the Virginia statehouse, and what an exciting day it’s going to be when Governor Northam signs those into law! And that was 20 years in the making, Eileen’s journey.”) She says that it’s teens of color in Philadelphia and Chicago and New Orleans, not just the Parkland kids we see on TV, who are organizing sit-ins and changing gun laws.

That’s been Dees-Thomases’s work since the march. Organizing, celebrating, and immortalizing women. She’s an activist’s activist, obsessed with the anonymous women, the overall-wearing women, the moms, the women of color who were ignored in the media—the women whose stories and successes were coopted by men. In 2012, after Sandy Hook, working with the filmmaker Susan Willis (“I hounded her for about six weeks”), she started conducting interviews of unsung female gun-violence heroes: moms who devoted their lives to the movement after their children's murder. Dorothy McGann, now 90, who organized to pass New Jersey's first assault weapons ban. When Dees-Thomases went to mic her, McGann said she had never been filmed before.

In 2016 she released Five Awake, a 36-minute documentary (“I personally wanted to make it a five-hour film”) about the group of women who, in the wake of extreme domestic violence in Louisiana, swiftly overhauled the state’s domestic violence laws, including passing a bill that banned domestic abusers from owning guns for a decade. Dees-Thomases moved to Louisiana to promote the film, and her older daughter was inspired by one of the activists to become a social worker. (“I say, damn you, Mary Claire, for being so inspirational! My daughter had graduated from business school!”)

Dees-Thomases' work is almost all volunteer. And that work “is really to uplift and promote the women activists,” she says. “They do things I could never do. Oh!” When Dees-Thomases was honored by Glamour, she was too nervous to say more than a few words at her own massive march. She says she’s inspired by Samantha Fuentes, one of the teen activist Parkland survivors. (“She was giving her speech, she threw up onstage, and she got up and finished her speech. She’s my hero!”)

Twenty years later she still believes that moms are the best advocates for gun-violence prevention—she loves the Parkland kids, she says, chuckling, “I look at those kids and say—they have some great moms!” You need moms to have a movement. You need moms to march, and then you need to know the march is meaningful only “if you are prepared to do a database collection.” You need to attract moms to marches because they are great volunteers, because they will help you create “a database rich with passionate people who put their bus deposits on their personal credit cards, and then go out and fill them with 50 people. That’s the kind of person you want.”

Dees-Thomses says, happily, petting a dog, that 2020 is the year, the year of change. The year of progress. Another great year, brought to you by moms.

Jenny Singer is a staff writer for Glamour.

Originally Appeared on Glamour