As Donations Pour in, Bail Fund Organizers Want to Overhaul the System

In the 17th century, political philosopher Thomas Hobbes famously wrote that without a supreme leader enforcing order through punishment, life would be “nasty, brutish, and short.” Centuries later, the idea that human nature instinctively bends toward cruelty is still a common one.

And yet, people seem to have an uncanny way of disproving that. Just look to the past two weeks. In the wake of nationwide uprisings—sparked by the killing of George Floyd, a 46-year-old Black man who died after a Minneapolis police officer knelt on his neck for nearly nine minutes—near virtual strangers across the country pooled millions of dollars into bail funds, or a revolving pool of money and resources that allow for someone’s release from pretrial detention. Seemingly overnight (and in the middle of a pandemic and historic unemployment rates, no less), these bail funds rose up the ranks of online virality as people compelled friends to give, posted screenshots of receipts, and matched donations.

Since graphic video footage of Floyd’s last moments of life surfaced online two weeks ago, thousands flooded streets across the world, a bold dissent against the police, institutional racism, and the all-too-casual dismissal of Black lives. As this multiracial coalition demanded justice for Floyd and countless others, the risk of arrest increased as cities set curfews and deployed the National Guard.

In response to this threat, the Minnesota Freedom Fund raked in $20 million to post bail for arrested protesters, an incomprehensible sum met within just five days after Floyd was killed. The fund soon after announced it would be pausing any further donations, saying in a statement on its website, “One week ago we were a small bail fund struggling to get anyone to listen about the harms of cash bail and pre-trial detention. We are now flooded with resources and we are going to take a beat while we marshal those. We have some big plays in mind.”

Other bail funds quickly followed suit. In New York City, organizations like Free Them All for Public Health and the Brooklyn Community Bail Fund shut down donations after raising hundreds of thousands of dollars in a matter of days. In Los Angeles, the Peoples City Council Freedom Fund has received well over $2 million. And in Chicago, the Chicago Community Bond Fund has asked that people redirect their money elsewhere after receiving more than $3.5 million from more than 75,000 donors.

The surge in donations has been pivotal for New York City’s Emergency Release Fund—a bail fund that prioritizes the release of people within the LGBTQ+ community, launched last year after Layleen Polanco, a transgender woman, died in solitary confinement when she could not afford a $500 bail. In the time between their launch in August and March, they bailed out 20 people, member Alex Tereshonkova told BAZAAR.com. Then, bolstered by COVID-19 and protest-related donations, the fund has bailed out 180 people since March.

How Bail Works

Once arrested, a judge sets a bail amount, an expense that can easily cost upward of hundreds of thousands of dollars, which must be paid in order for a defendant to avoid pretrial detention. It’s meant to incentivize a defendant to appear in court, since the money is then returned upon their court date. In practice, however, it usually means that those who cannot afford bail wait for months or even years behind bars—all without a conviction.

“Cash bail’s whole existence is on the reliance that poor people aren’t able to post their bail and get out of jail,” Tereshonkova says.

Robin Steinberg, CEO and cofounder of The Bail Project, echoes this sentiment. “What’s happened over the years in America’s criminal legal system is that cash bail has been used—not as a form of release—but actually as a form of incarceration and control,” she says. “So, wealthy people can pay their cash bail and fight their case in a position of freedom, and people without money actually have to sit in jail cells and endure the harm and the violence of being in jail.”

A 1987 Supreme Court ruling in the case of United States v. Salerno granted judges the ability to set bail by assessing the supposed safety of the individual’s release to the public. However, opponents argue that any equivalence between public safety and bail amounts is a farce. “One of the core achievements of bail funds has been to show that most people that they post bail for show up to court. They don’t abscond and they don’t commit another crime before their court date,” says Wanda Bertram, the communications strategist of the Prison Policy Initiative. “That tells us that holding people in jail before their trial by default is not only questionably constitutional, but it’s also, in most cases, unnecessary for public safety.”

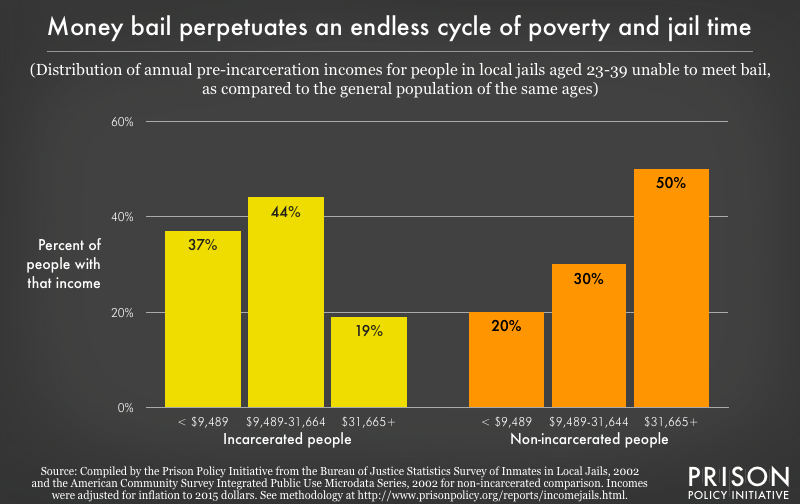

And, like the full gamut of the American justice system, the ability to post bail is unsurprisingly rife with racial discrimination. A 2016 report by the Prison Policy Initiative found that most people sitting in jails because they cannot afford to make bail have a median income of $15,109 prior to their incarceration, with white men having the highest pre-incarceration income at $18,283 and Black women having the lowest pre-incarceration income at $9,083.

Prison and jail populations also disproportionately represent people of color, but especially Black people. In a 2018 study, The Sentencing Project reported that Black people are nearly six times more likely to be incarcerated than their white counterparts. And, as another study by the Prison Policy Initiative found, hundreds of counties across the country have a “10-to-1 ratio of over-representation” of incarcerated Black people. In other words, the portion of Black people that make up these counties’ prison populations is 10 times larger than the amount of Black people living in the surrounding county.

Sharlyn Grace, the executive director of the Chicago Community Bond Fund, illustrates the disparities in her city’s jail makeup. “It is really important in understanding the work in Chicago to know that it is overwhelmingly Black people in Black communities who are harmed by money bail and pretrial jailing,” she tells BAZAAR.com. “Twenty-five percent of people in Cook County are Black, but 75 percent of people in Cook County Jail are Black.”

How Bail Funds Began

Historically, bail funds emerged as a response to American captivity, when Black communities banded together to purchase the freedom of their enslaved loved ones. This tradition of communal caretaking provided a launching pad for modern bail funds: In 1920, the American Civil Liberties Union established a national bail fund in response to the incarceration of political dissidents as anti-Communist hysteria ran high; again, in the late 1940s, the Civil Rights Congress formed another national bail fund during the Second Red Scare, amassing hundreds of thousands of dollars in donations; and, during the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, various bail funds were set up to provide for the release of those fighting against segregation and Jim Crow laws. The history of American bail funds, then, can easily be traced through the history of radical American resistance.

“They’re predicated and built out of the idea that communities are standing up for community members,” says Pilar Weiss, director of the Community Justice Exchange. “It's just a stranger bailing people out, but it's not based on personal relationships.”

Bail funds, which fundamentally differ from the services that bondsmen provide, operate on a revolving basis since the money is returned once a defendant appears at their court date, meaning that a single donation could potentially contribute to the freedom of multiple people over a vast period of time. A bondsman, however, usually requires an individual to pay at least 10 percent of their bail upfront, thereafter using some form of collateral to make up the rest of the bail to the court. Once the defendant returns to court, which they usually do, that 10 percent fee is returned to the bondsman, which they then keep as a profit.

“So, it’s really like free money for the bondsman,” says Cherise Burdeen, one of the executive partners for the Pretrial Justice Institute. “Just another form of exploitation. And the thing that sort of gives you the pit-in-your-stomach sickness about it is that it’s not like it even works. It’s not even like it’s got a point, right?”

Burdeen reiterates that most people who have been bailed out by community bail funds return to court on their own, even as they lack the incentive of having their bail fee returned to their own wallets. But what about those who do happen to miss their court dates? “It’s not an absconding or a flight-from-justice kind of thing,” says Burdeen. “It’s more like a missed appointment. Either they couldn’t get off work or get childcare or eldercare. In many places, there’s no public transportation, so there’s no way to get to court for some folks.”

Bail Reform Isn't Enough

While bail reform initiatives have swept Democratic agendas in recent years, organizers see some legislative packages as toothless. New York, for example, serves as an ultimate lesson in the limits of reform. In 2019, the state passed a monumental reform bill that eliminated cash bail for most misdemeanors and nonviolent felonies, a move intended to drastically reduce jail populations. Police, law enforcement officials, and anti-reform Conservatives swiftly retaliated, with tabloids running salacious headlines suggesting public safety was now in dire threat. By 2020, the state cowed. Governor Andrew Cuomo and state lawmakers scaled back on the bail reform package, making more than a dozen more crimes eligible for cash bail.

“‘Reforming’ bail is a mirage,” say the organizers behind New York City’s Free Them All for Public Health in an emailed statement to BAZAAR.com. “It doesn’t get us closer to a future without cages, cops, and the courts that hand people back and forth between the two. What our communities need is the abolition of pretrial detention in all its forms, which is a step towards freeing all of us from the carceral system.”

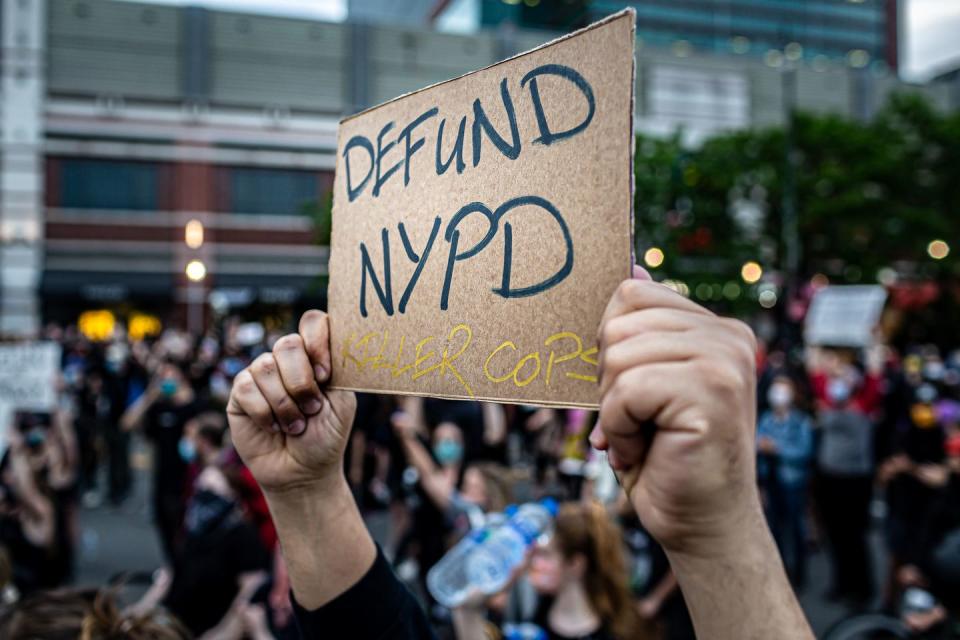

Once ideas suspended on the periphery of mainstream discourse, abolition, like bail funds, has rode a swelling wave in recent weeks to the shores of national attention. Graphics explaining the ideology in digestible bullet-pointed bits and Instagram-feed-friendly aesthetics have fanned out across all corners of the social media landscape. Establishment news outlets are suddenly running explainers on what abolition would look like. And at protests, it is nearly guaranteed one will see dozens of signs calling for a defunding of the police.

Simply put, abolitionists—many of whom have set up these bail funds—believe that a just world and the presence of police, prisons, and mass incarceration cannot simultaneously exist.

Of course, abolition is anything but simple. This holistic approach is meant to tackle all fronts of the carceral system at large, divesting resources away from the country’s bloated police department budgets and investing instead in community resources. The thinking goes that crime is the symptom of larger social inequalities at play, when vulnerable people aren’t able to survive without resorting to extralegal means. Thus, ending those social inequalities is a much more effective way of cutting down crime than it is to pour money into policing and jails. In other words, abolition is not just about abolishing police or detention facilities, but about abolishing the conditions that lead to their creation.

“Bail funds are a necessary bandaid on the structural problem of pretrial incarceration, but they are in no way a solution,” Free Them All for Public Health’s statement says. “It’s wonderful to see thousands upon thousands of people contributing to that effort, but that’s not where the work ends.”

For these organizers, to end cash bail without a concerted effort to end other aspects of the justice system would be to sever a single head of a Hydra rather than the whole beast.

“We’re, in a way, organizing ourselves out of existence,” says Ana María Rivera-Forastieri, the codirector of the Connecticut Bail Fund, “if we’re doing our jobs right.”

She emphasizes that the country’s current outrage is forcing a reimagining of the entire system. “For a long time, people have been trying to be at the table, trying to be in dialogue, trying to ask for elected officials to engage in certain things,” she says. “That hasn’t worked. So these uprisings are opening up an opportunity to actually push the agenda that people believe in.”

Some politicians are beginning to take note. On Sunday, after two weeks of nonstop protests, the Minneapolis City Council announced plans to dismantle the police department. “We are here today because George Floyd was killed by the Minneapolis Police,” said City Council President Lisa Bender, per The Appeal. “We are here because here in Minneapolis and in cities across the United States it is clear that our existing system of policing and public safety is not keeping our communities safe.”

In a world without high-handed punishment, abolitionists and community organizers are pushing back against the Hobbesian idea that life would be “nasty, brutish, and short.” In fact, abolition itself, as forged by great Black feminist thinkers like Angela Davis and Ruth Wilson Gilmore, can easily be argued as a radical and transformative doctrine of love. Its tenets are steeped in the idea that we as a community care for each other far better than police are able to.

And what is the fact that strangers across the country continue to open their wallets to post bail for people they will most likely never meet if not a testament to that?

You Might Also Like