‘I don’t have to convince anyone’: How a Kosovo refugee became the biggest name in watchmaking

Geneva’s old town is a tranquil backwater, yet every day groups gather outside three store fronts. These are the Akrivia workshops, and they come to admire the work of watchmakers, case makers and strap makers. This would be impressive if the workshops were owned by one of the billion-dollar watch groups, but it becomes something of a horological fairy tale when you realise that the company is the dreamchild of a refugee who, at 37, is making some of the most innovative, highly sought-after watches in the world.

Born in 1987 in Zhegër, Kosovo, Rexhep Rexhepi (pronounced ray-jep ray-jepee) was brought up by his grandmother while his father worked as a restaurateur in Switzerland, sending money home and visiting when he could. ‘When he came back,’ says Rexhepi, ‘he would be wearing this watch – an Omega or a Tissot – the brand didn’t matter, but I would take it from his wrist and listen to the tick-tock. It was a piece of magic and I was intrigued.’

On 28 February 1998, the Kosovo War broke out, displacing more than a million Kosovar Albanians. Rexhepi, then aged 11, and his two siblings were sent to Switzerland. ‘Integration was slow and it really wasn’t much fun,’ he says. ‘You try to find yourself by finding your own community. I started to go to the library and read books about watchmaking. I also did a bit of skateboarding and through this I met a neighbour who was a watchmaker, and he encouraged me to give it a go.’

At 15 Rexhepi beat 300 other hopefuls to win a watchmaking apprenticeship at Patek Philippe. He spent three years between the manufacture and watchmaking school, then two in Patek’s workshops, where he first saw the 10 Day Tourbillon, and he vowed that one day he would hold a tourbillon he had made himself.

In 2007 he moved to the independent movement maker BNB Concept, where a year later he was in charge of a team of 15. There was one more important step for Rexhepi: to work with a traditional independent watchmaker. Through a friend, he was given a trial and subsequently a job at FP Journe – one of the few modern watchmakers to design and build movements in their entirety. ‘I have a lot of respect for Mr Journe,’ says Rexhepi. ‘He understood what I wanted to do and what I needed to learn. I stayed with him for two years, but could have stayed for 10 more if I hadn’t had the offer to work with a friend on some prototyping in return for engineering help to build my own watch.’

Rexhepi had no idea of the hardship ahead. At 25, with detailed sketches but no actual watch to his name, no one was willing to risk commissioning him to create a hand-made timepiece that would run into tens of thousands of Swiss francs. His confidence wavered for the first time in his career, and it took two years for his self-belief to return: ‘Eventually I thought, “I’m doing this. I know why I started and I will make a movement of the best quality. I will focus on it.” When you put only good energy into your work, you transmit something different, and from this moment, every person I met understood what I was doing and everything changed.’

He unveiled his debut watch in 2015. ‘That first client understood what I was doing,’ says Rexhepi. ‘And I think he felt he needed to help me. I’m not even sure he liked the watch. He was just a good guy, and I will always remember what he did.’ That AK-01 Tourbillon Chronographe Monopoussoir – the tourbillon he had promised himself he would make – and many of his subsequent pieces bore not their maker’s name but the word akrivia, Greek for precision. ‘My father told us we should always defer to the Swiss. So I couldn’t be the guy coming from Kosovo and making Swiss watches with my name on them. It sounds stupid but I just couldn’t do it.’

Over the following three years Rexhepi won respect among collectors. The rare, handmade nature of his watches, their consistent quality, and his drive to always do better meant that by the time of his debut at the Baselworld trade fair in 2018, he had already developed six unique calibres – five of them tourbillons – under the Akrivia name.

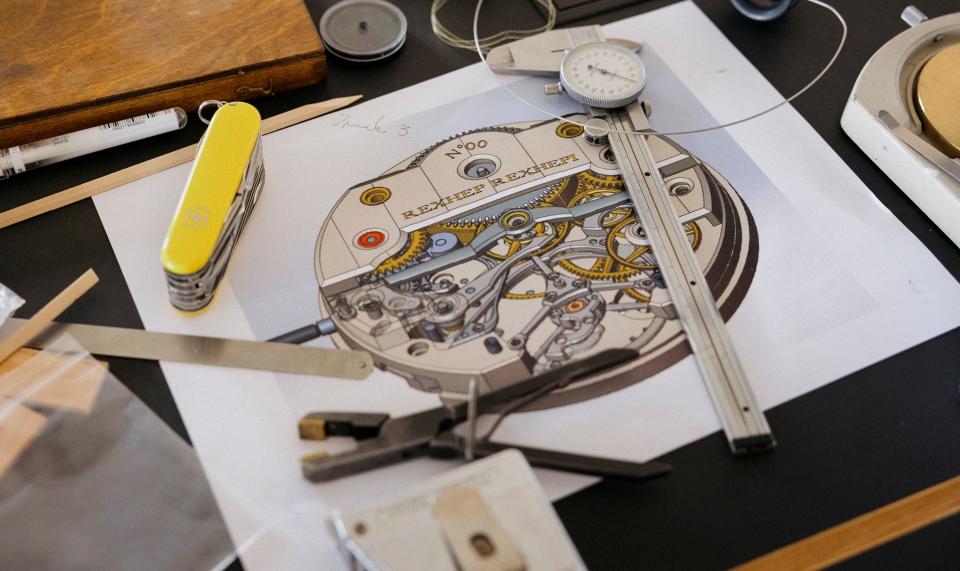

And it was at this point that he finally decided the time was right for an eponymous collection, introducing the Rexhep Rexhepi Chronomètre Contemporain I (RRCC I). More classical in style than previous watches, it eschewed unnecessary design, showcasing the handcrafted movement and precise finishing that took him from underground sensation to one of the most sought-after makers in the world. Later that year he received the highest industry recognition when the RRCC I won the Grand Prix d’Horlogerie de Genève Best Men’s Watch prize (as did the RRCC II four years later).

A natural successor to George Daniels, Kari Voutilainen and FP Journe, Rexhepi too is breaking new ground, following his own path, embracing challenges he meets along the way – and all without any external investment.

This need for independence is something he comes back to again and again: ‘I grew up in a free Kosovo and suddenly we were afraid because the [Serbian] police had the right to do anything,’ he says. ‘So freedom has been very important my whole life. I don’t have to convince anyone that I am doing a good job, and I am free to evolve at my own pace.’

While many bigger brands have teams of prototype engineers, at Rexhepi’s workshops it is all done by him, as he believes products designed by committee lose their character. He makes 40 to 50 watches a year with a team of 25 including backroom staff. By staying small, he says, he can help each one of them to grow: ‘When we work together, we are stronger.’

Rexhepi designs and builds every prototype. When he is happy, components are delivered to the watchmakers to assemble, with Rexhepi teaching them as they go. From design to completion a project can take six months to five years. To date, Rexhepi has launched 10 movements, and each brings something new. Hailed by specialists as a ‘modern independent genius’, Rexhepi is typically dismissive of the hype. ‘I’m not a genius,’ he says with a shrug. ‘I don’t believe in genius. So, you know, I’m just trying to slowly learn to do better.’

The machinery in Rexhepi’s workshops dates back to the golden age of Swiss hand watchmaking. He has restored lathes, stamping presses and machines for milling and drilling from the 19th and early 20th centuries.

As for his inspiration for the workshop set-up, Rexhepi looked to the UK and the father of independent watchmakers, George Daniels (1926-2011). ‘George’s book Watchmaking is the bible,’ he says. ‘I saw all the pictures of his machines and I wanted to have exactly the same because I wanted to create like he did and like FP Journe and Kari Voutilainen did after him. These pioneers did so much. Today, I have more tools, more information and more examples. They were working from intuition, and this is why I have so much respect for the past. Working with these old machines pushes you to think differently, to be a little more minimalist and not take the easy way.’

While prices for a Rexhepi creation are £50,000 to £350,000, and waiting lists run to years, last year a RRCC I in pink gold sold at Phillips Hong Kong for close to £750,000. Will this make him reset his prices? ‘The original price for the RRCC I was a little under what it actually cost, but it was a way for me to show the world what I’m able to do, and to attract more people. I couldn’t believe it when I saw the sale price. But I can tell you this will not affect my prices,’ he says. ‘I don’t want to play that game. I charge what I need to so I can invest in my company, look after my young family, eat good food, buy good tools, and maybe buy some watches. Of course, buying just to sell is not correct because so many people want a watch from us. But a few years ago, nobody wanted my watch, so the fact that today people do want them makes me happy.’

Last year also saw Rexhepi collaborate with Louis Vuitton on a 10-piece watch edition to support the Louis Vuitton Watch Prize – a financial award and a one-year mentorship with Louis Vuitton’s La Fabrique du Temps (LFdT) manufacture for a young watchmaker. The LVRR-01 Chronographe à Sonnerie collaboration reunited Rexhepi with his one-time bosses at BNB Concept, Michel Navas and Enrico Barbasini, who now helm LFdT. ‘I started with a chronograph tourbillon ebauche at BNB Concept so this was a way of paying homage to Enrico and Michel,’ he says. ‘But I added the sonnerie, which chimes every minute, because the student has to do something to show the teachers what he learnt from them.’

This collaboration enabled Rexhepi to combine complications in a way never seen before and also marked another major milestone in his business: the last time akrivia will be seen on one of his watch dials. Going forward, all dials will bear the legend REXHEP REXHEPI.