Dolph Lundgren, Action Auteur, On Fake Guns, Real Cocaine, and Kelsey Grammer

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Who is Dolph Lundgren, really? It’s a question that’s been on my mind—well, mostly since I was offered the opportunity to interview him, but certainly before that, too, if I ever stopped to think about it.

To most of us, Lundgren is still and maybe always will be Ivan Drago, the robotic, mostly-monosyllabic Soviet-smashing machine from Rocky IV. As he’s said himself of the movie’s premiere in 1985, “I walked into a Westwood theater as Grace Jones’ boyfriend, and walked out 90 minutes later as the movie star Dolph Lundgren.”

That said, it’s probably not an insult to say that Dolph Lundgren the person is a lot more interesting than Dolph Lundgren the actor. In a way, he was famous before he was famous. Raised in Stockholm, the 6’4” Viking with the cartoon jawline initially planned to follow in his father’s footsteps as an engineer. A chemical engineer, specifically—a discipline for which Lundgren received several scholarships, including a Fulbright to MIT.

That same father was also abusive, however, inspiring Lundgren to seek an outlet for his feelings of anger and aggression. He discovered it in the form of karate. He excelled at that, and so for a time he was Hans Lundgren, the karate champion chemical engineering scholar, attending Washington State, Clemson, and the University of Sydney in Australia while competing in martial-arts competitions and working as a bouncer. It was in Sydney that he met Grace Jones, the singer, actress, and gay icon. The two became lovers (possibly because they knew that together they’d make an irresistible sight gag?). Before long, Lundgren had moved to New York, changed his name to “Dolph,” and was hanging out at Studio 54 with Andy Warhol.

Lundgren has spoken about Jones bringing four or five women back to their apartment some early mornings for group sex. Jones has talked about setting Lundren’s clothes on fire after their breakup. It was a different time. Of course, he’s been married twice since then, and has two grown children.

So what do you ask him about? Karate? Chemical engineering? Studio 54? And oh yeah, doesn’t he have a movie he’s promoting? It’s called Wanted Man, which Lundgren directed and co-wrote, which co-stars Kelsey Grammer. It’s actually Lundgren’s eighth directing and seventh writing credit. Though let’s be honest, you probably haven’t seen many of these. Diamond Dogs? Missionary Man? Castle Falls?

In Wanted Man, Lundgren plays a racist cop in the fictional, San Diego-like bordertown of Del Vista. Grammer plays his retired counterpart. At one point, over beers at a strip club, they complain about how entitled these migrants are these days, coming to the US, expecting everything. Lundgren’s character lands in hot water after he’s caught on a bodycam calling a suspect a “lowlife Mexican”; as penance, he's sent across the border to escort some sex workers back to Del Vista after they witness a murder.

Some gunplay ensues and Lundgren's cop falls for one of his charges (Christina Villa), and by the end it seems as if the character's had a change of heart. The film is much more ambiguous on that point than it is in establishing Lundgren’s character as a guy who resents Mexicans in the beginning. Knowing that Grammer is one of Hollywood’s semi-rare semi-open Trump supporters, it does make one wonder if this performance was mostly Grammer speaking things he actually believes out loud. Lundgren is cagey when I ask him about this, although it’s certainly possible he’s never thought about it.

“I’m not aware of his politics,” Lundgren will tell me. “I know they’re rebooting Frasier.”

All of these aspects of Lundgren’s character are hard to square if you imagine a person embarking upon life with a certain end goal in mind. Chemical engineer. Karate master. Movie star. Director. Much easier if you imagine a life tracing a path through a series of intriguing opportunities. Let’s be honest again and acknowledge that probably a lot more of those opportunities come your way when you’re hyper-intelligent, athletically gifted, photogenic, and physically imposing.

Life tends to quiet down for many of us when we’re over 60 (Lundren is 66 now), but getting to play with squibs in the desert for a few months at a time doesn’t sound like a terrible way to spend what normally are one’s retirement years. And so maybe it’s more interesting just to ask Dolph Lundgren about where he’s been and what he’s seen than to try to figure him out. He seems mostly to take what comes, and who can blame him?

GQ: So you had a Fulbright scholarship to MIT at one point before you were an actor, right?

DOLPH LUNDGREN: Yes. I started studying chemical engineering when I was teenager. I had scholarships to Washington State University, then I went to University of Sydney, and then finally, I was going to go to MIT on a Fulbright scholarship to get a PhD. But I met this lady, Grace Jones, who was a singer, and I went to Studio 54 and ran into Andy Warhol, David Bowie and a few others. And I decided, “Hmm.” I was always into acting and performing arts, and I decided maybe I'll give that a shot.

“This seems more interesting than being in a lab.”

It kind of beat shaking a test tube—it was better to go to 54. What happened was I went to an acting class with this guy named Warren Robertson in New York. And I had a lot of issues, trauma from my childhood. My dad was kind of violent, and I'd never really dealt with that. I was also a fighter at the time, a karate champion, but I felt through acting, I could sort of express that somehow. I had expressed it through martial arts, but with that, you kind of just hijacked the emotion and used it. The acting felt more satisfying in some way and that's the reason I really decided to quit engineering.

A lot of people get into crazy situations and crazy scenes because they’re in show business. It seems like you were part of some of those things before you werein show business.

It was a crazy ride, for a Swedish kid to come to New York. Grace was at the pinnacle of her career, and I hung out at 54 and I met all the photographers and all the fashion designers. Gianni Versace made me a leather jacket before he got famous, when he came over from Italy. And there was a lot of partying and drinking. I was always training and I was always busy. I always knew that I was probably going to have to break away from that life eventually, being up all night. When you're 23, 24 and you're in great shape, you can do that, you can get up and run at 5:20, even though we went to bed at four. Of course if I tried that now I'd be in the hospital. But yeah, I went through a lot of that, and then when I did the Rocky movie I became kind of famous overnight because it was a big hit. And it was during the Soviet-American nuclear standoff and it was a big deal, this movie. Dealing with fame and dealing with all of that, took me a number of years to recover from that too.

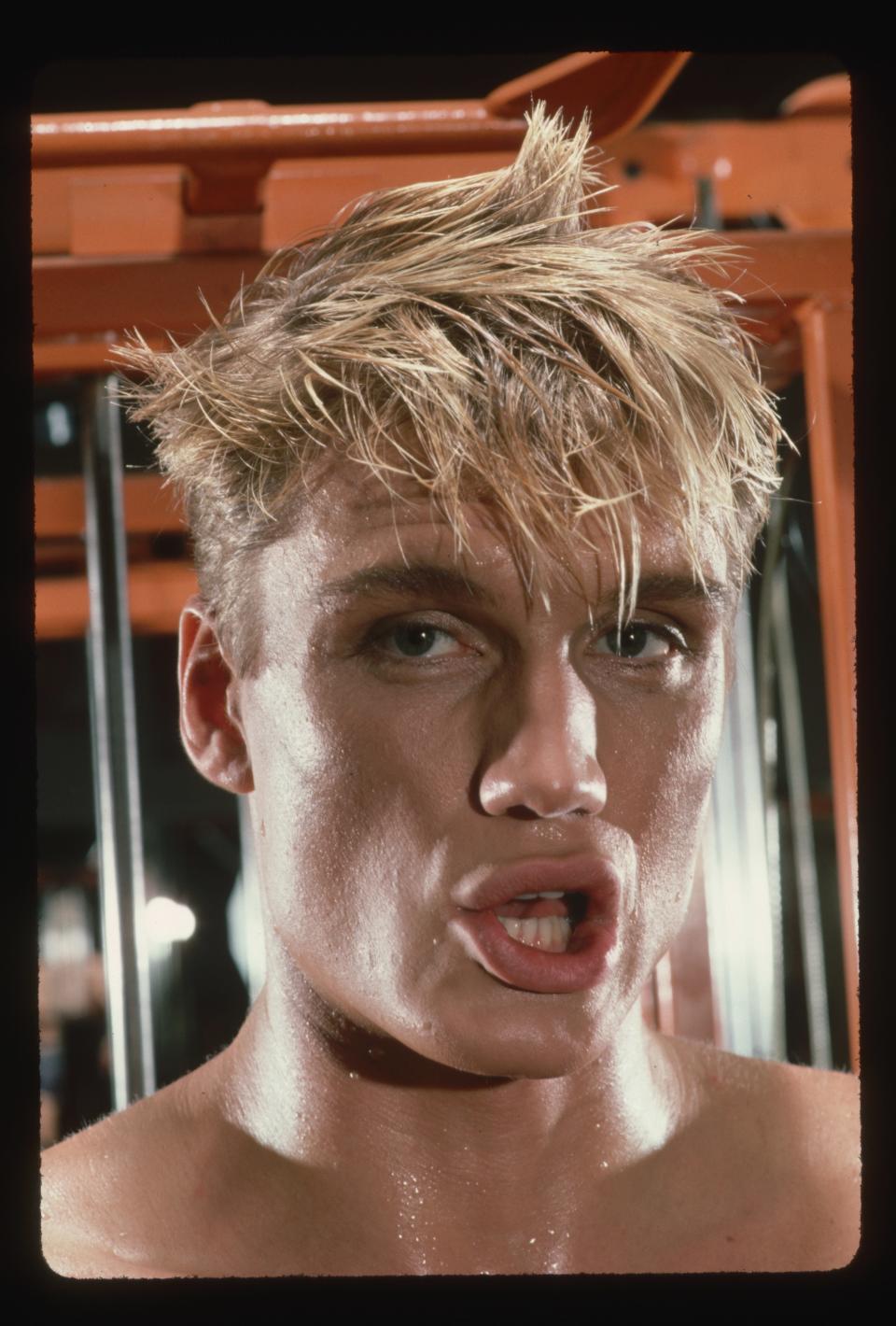

Dolph Lundgren at Workout

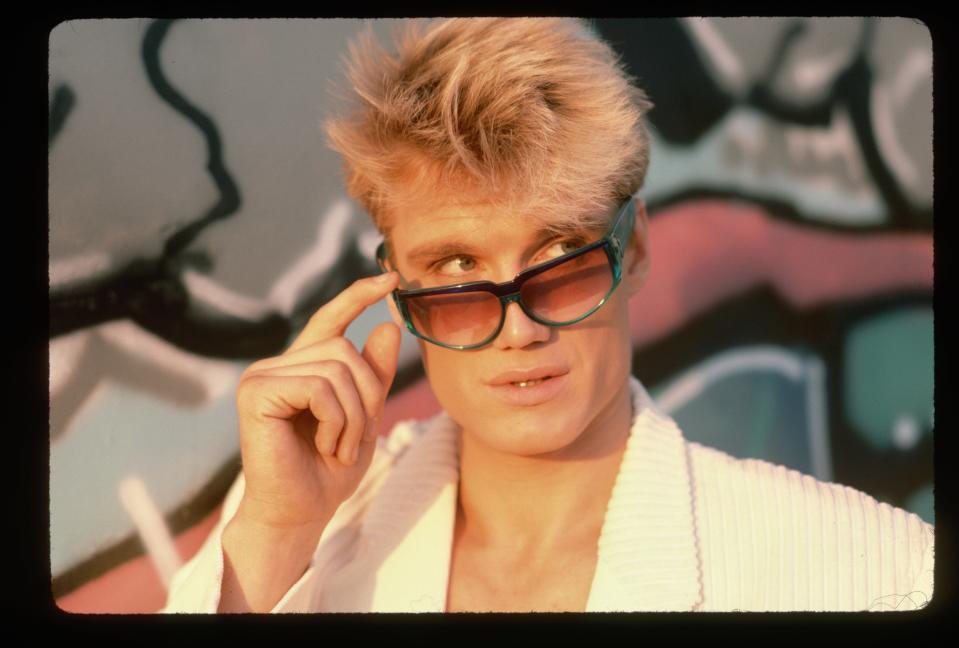

Dolph Lundgren

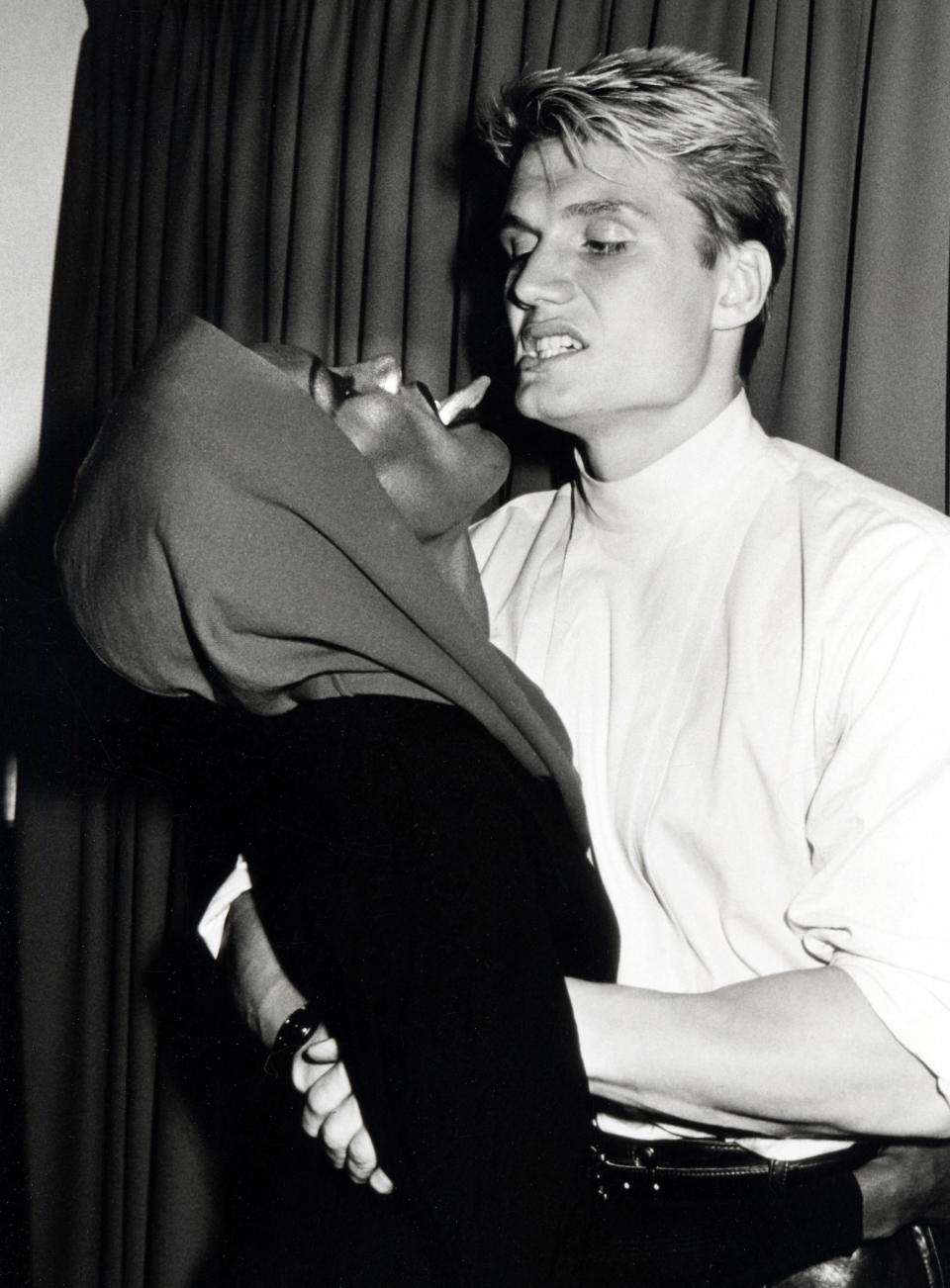

Grace Jones Sighting at Les Tuilieries Restaurant in New York City - October 8, 1985

When someone like Gianni Versace, who's not famous at that point, comes up to you and says, "Hey, I made this leather jacket for you," what’s that like? What do you remember about him?

I thought he was a really nice guy and that he was very talented. I stayed friendly with his sister, Donatella as well, after he died. It was terrible. But a lot of those people that I hung out with in New York are not with us anymore. A lot of them died from AIDS. It was a crazy time, it was.

It seems like people love to mythologize that period of New York. How would you explain that scene to people that didn't experience it?

Well, it's before iPhones, if anybody was going to take a picture of you, they'd have to pull out a pretty big camera with a flash on it, especially at night. So you were pretty safe as far as if you were a celebrity, nothing was going to happen. That was the difference, I think that there was drug use, and the drug use was not a social problem yet because there was no crack. People were doing cocaine and other drugs, but it was just the well-to-do people that did it, so it wasn't really [considered] a social issue. Obviously it went on to ruin a bunch of careers, but I think it was, I would say it was a fun time. You could run into big celebrities at a club, people went out and socialized. In those days, New York was a little dangerous, but it was also a little bit more colorful, I think. The fashion industry wasn't taken over by corporations yet, it was run by individuals. Studios too, by the way.

And then you go from that to being in Rocky IV and you're fully in the midst of ‘80s Hollywood. How was the movie business then compared to now?

I think the decisions were being made by fewer people. There wasn't as much corporate ownership of the studios. And the head of the studio would make the decisions with a couple of producers, it wasn't like a committee. So I think it was a bit easier to be creative and do the medium-budgeted pictures like a Rocky IV, or Scarface or Goodfellas. Or any of those movies where they were independently produced, but they had a decent budget. It wasn't superhero time where it's $200 million, and has to be PG and all of that. In one way, it was serving the artist a little more. That's what I felt, anyway. I get a feeling now that there's so much at stake with the big tentpole movies, the editors get notes from 20 people. It just seems like the R-rated movies for grownups, there are fewer of those.

So you wrote and directed this movie. You've been doing that for what, 20 years now?

I started rewriting stuff, I am not really a writer. I mean, it's hard for me to sit with a blank page and write stuff from scratch. I think what I do is as a director, I rewrite things because of budget, or because of story issues, maybe. But I've been directing on and off for 20 years, yeah.

Was that something that you started because you really wanted to direct or was it more a way to control your material as an actor?

I think it was a bit of both. What happened was, in the first directorial effort I had [2004’s The Defender, on which Lundgren stood in for an ailing Sidney J. Furie], the director got sick. And I had been working on the script with him. They said, "Well, who are we going to hire because we're two weeks away?" He said, "What about Dolph?" And they're like, "Who? Dolph? What are you talking about?' Well, no, he is really good with story."

So I got that job and then it worked out pretty well. These small movies, they're hard to bring in on budget, on time. And I found that I have more experience than most other directors that they could hire, that they could afford, or that are in that marketplace for, so I might as well do it myself.

So in this movie, was it your idea to bring Kelsey Grammer in, or did a producer put you guys together?

It was a producer who came up with the idea. I knew him from Expendables 3, I knew him socially. Nice guy, and we got along, and one of the producers just brought him up. And first I wasn't sure because he comes from comedy, but then I realized that it was a really good idea because he just lights up the screen with his delivery and he's very experienced. And because his character has a bit of a dark side, it kind of works that he's that way. That he doesn't play the darkness, he plays the other side of the character.

Do you think that he gets less work nowadays because of his politics?

I'm not aware of his politics. I'm not sure how that works. But I know they're rebooting Frasier.

Oh, yeah.

I'm not aware of his politics—really. Look, in my opinion, personal opinion and your politics should not affect... Humphrey Bogart–well that's a bad example because he was against the blacklist and all of that, he was very progressive. But Gary Cooper, or somebody…

Yeah, we didn't know much about them back then.

Right, exactly.

This is a relatively small independent film with a lot of gunplay and action in it. Has what happened on the set of Alec Baldwin’s movie changed the way you and your collaborators approach gunfights and other action scenes in a project like this? Are you starting to see new safety precautions being put in place?

I think it did have an impact. I think people are much more aware of what could happen. It became an insurance issue, because I didn't want to use fake guns and use CGI muzzle flashes and CGI hits everywhere, because they don't look as good—they look a bit fake. The squib hits are much better. It's hard to replicate them. And muzzle flashes are hard to replicate too. But there are these new guns that they've come up with, I think partially because of the Baldwin situation. They're called non-guns or something, it's like a real weapon, but you put another cartridge in it, there's no barrel. It's not like you put a blank in a real gun, but it looks like a real Beretta but put a cartridge in, it fires, shoots out a muzzle flash and ejects a shell. But the whole thing is fake. So there's no way it could lead to an accident. We use those for most of the weapons.

So that has changed and it made it easier. Because we were also shooting in New Mexico, and that's where it happened, so people [there] were very concerned about it. But I told them too, I've done so many action movies. And you do Expendables, there's an armorer that comes up and shows you the weapon and says, "Hey, Dolph, take a look." And you look through the breach, you look at the magazine, he gives it to you. And you know the guy is some ex-Army specialist. And then I would blank fire it myself into the ground, just to make sure. So I don't know what happened on that movie, but certainly whoever did it didn't do a professional job.

Originally Appeared on GQ