This Service Dog Visited All 63 National Parks in One Year

This article originally appeared on Outside

On July 20th, Texas resident Brad Sailer and his epilepsy alert dog Ranger completed their quest to travel to all 63 national parks on July 20, 2023 in an effort to raise awareness around accessibility in the outdoors--making history in the process. Pet dogs are not allowed inside all national parks, so Ranger (whose access is allowed by the Americans with Disabilities Act) became the first dog to visit every park in the National Park Service’s system. Along the way, they faced bears, flipped cars, and odd run-ins with locals, but also an enduring sense that our public lands are truly for everyone, regardless of ability. Sailer talked with Outside's Emily Pennington the night before finishing his journey.

Going to all the parks is something that I've always wanted to do. I had a lifelong dream of being a park ranger, and I worked in EMS and disaster response for many years, but when I got hit with late-onset epilepsy in my early thirties, my whole career stopped. A few years after that, this quest to visit all 63 parks began.

I loaded everything into my Ford Explorer on August 15th, 2022, including Ranger and my girlfriend, Halie, and we headed towards Petrified Forest for our first park. I only had a rough map drawn out of where I wanted to go, but I learned very quickly that it takes a bit more planning and looking into the future to nail down things like camping and accommodations. We car camped at a lot of KOAs and on BLM land, only camping in the national parks every once in a while.

After Petrified Forest, we drove west to Joshua Tree, which really stood out to me, because it was the off season, so nobody was there. We put up our hammocks and just camped under the stars. There were coyotes howling and stars everywhere. It was absolutely beautiful and peaceful, like the whole world belonged to us. We continued all the way up the West Coast, hitting parks along the way.

Ranger, who's part Australian Kelpie and part Malamute, is an epilepsy alert dog. He'll give me some hints if I'm going to have a seizure, which hasn't happened for a long time, but his main job is to alert other people that I'm having a seizure. If I go down, I need someone to flip me on my side and make sure that I'm safe, so I don't choke on my own vomit. People can die when they have a seizure on their back and there's no one there to flip them over.

Not everybody understands the Americans with Disabilities Act or service animals in general and how those laws work. There's also a lot of recent controversy with emotional support animals that really cranked up a lot of anger in our country. It's an extra struggle for people with unseen disabilities.

I've even seen signs popping up in places that say "only seeing eye dogs allowed," which is technically illegal. A lot of people, when they think of service animals, they think of blind people. They don't think about people with epilepsy, or people with PTSD or anxiety. There are so many different disabilities that you just can't see, and I think that that brings a lot of judgment. I've had some really nasty interactions with people because of that.

The worst incident that happened was actually in Yosemite. Ranger and I were camping in the valley, and usually, no dogs are allowed in the walk-in campground we were staying at. But, as I said, he's an ADA service animal, which are completely welcome in any campground. It was around 11:30 at night, I was cooking dinner by my campfire, and a park ranger responded to a domestic dispute that was happening about three campsites down from us. He came over to ask us if we had heard anything, and when he looked over at Ranger, he said, "You can't have your dog here." I explained that he's a service animal and he responded by saying, "That is not a service animal. I know a service animal when I see one."

And I had to argue with him. He was not very nice about it. Eventually, he left us alone and said we had to get out of there in the morning. And the entire time, Ranger was wearing an identifying vest and a collar with tags.

My last service animal passed away a few years ago, and when he did, I spread his ashes at Redwoods National Park. Revisiting that site was really meaningful to me. Crater Lake stood out a lot, too, because that was the park I had most wanted to go to when I first fell in love with parks at age thirteen. Seeing it in person was mind-blowing. It was raining when I arrived, so we stayed in the camper in the pouring rain for a couple of days, and we still had a blast, because the lake still looked so beautiful. Then, in a twist of fate, on the last day, the clouds broke as we were pulling out, and the sun came out and hit the lake, and I got to see it in full bloom. Actually getting to see that that brilliant blue made me think, "Thank you, universe."

We did Grand Canyon, Zion, Bryce, White Sands, and Guadalupe Mountains on the way back to Texas from Oregon. Once back in Texas, I realized that I needed to start focusing on those parks that were going to be really difficult to plan for, like Virgin Islands, American Samoa, and everything in Alaska.

Halie and I ultimately broke up, and I took two months off for the holidays to sit down and plan the rest of the trip, because it was really clear that I needed to put some thought into thoroughly mapping it out.

I also had to start doing the piles of paperwork for Ranger to bypass quarantine in Hawaii and American Samoa, which was one of the most challenging parts, logistically, of the whole trip. He had to have a separate health certificate for each entry between different Hawaiian islands, then two more for his entry to and exit from American Samoa. In addition to that, he needed a specialized rabies blood test that can only be processed at one of three labs in the United States-and it usually takes them six months to process those tests.

I was ready to fly to American Samoa and Hawaii before I was going to get back on the road, and after those, going east would be easy in the spring. I drew a line of the most direct path from Florida, towards Congaree and up the East Coast hitting every park along the way.

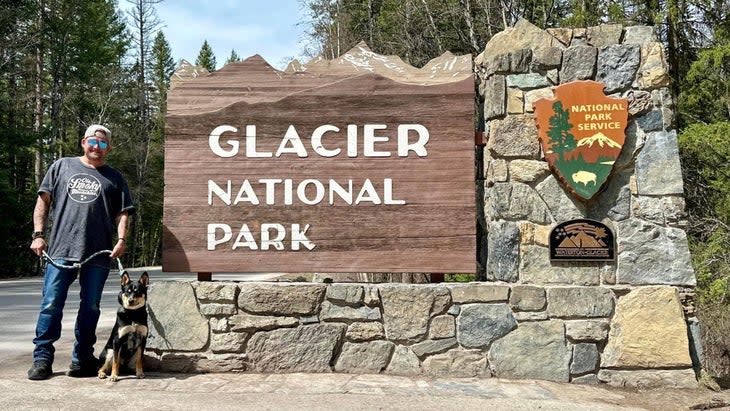

Ranger and I basically did a giant circle out east, then went across the northern part of the U.S., through Glacier and North Cascades, all the way to Vancouver. I feel like my whole last month was spent driving the Alaska-Canadian Highway. It took 11 days each way to drive, which was its own adventure.

The highway starts at Dawson Creek in British Columbia, and I was about 80 miles in when I swerved to miss a pothole, and my car tires caught on its edge, causing me to roll and flip three times. I completely crushed my Ford Explorer. It looked like a tin can. Miraculously, I walked away with what I thought was just a scratch on my head (I found out later that I actually cracked a few ribs). And Ranger was completely unscathed.

After rolling and flipping my car, people told me to take a break, and I said, "Hell no."

You can't access all the Alaska parks by car--you have to fly to five of them. Ranger only had to be crated on the plane out to Kobuk Valley. When we used Wright Air to go up to the small Native village of Anaktuvuk Pass in Gates of the Arctic, they just let him ride in my lap. Katmai was the hard one, because the float planes usually take you in to a place called Brooks Camp, but even service animals are not allowed at Brooks Camp because of the high concentration of bears there. I thought that was going to be a showstopper, and I was reaching out to people in D.C. to try to figure out how to get around it and eventually I found a float plane that would take me into a different part of the park.

It was really important to me to not just go in, get a stamp, and tag a park. The parks each had to be experienced, or to me, it didn't count. I had some pushback from some people when we were looking at Katmai and Kobuk Valley, asking why I couldn't just get into airspace. But, in my opinion, boots had to be on the ground. Ranger's paws had to be in the park. I didn't want to cut corners.

But I also wanted to be respectful of the environment. Channel Islands is a good example. There's a reason that dogs aren't allowed on that island: the endangered fox population there. So even getting to a place like that, I have to be very cognizant of the impact that we're having while we're there and where we're walking. We stuck to one big long trail that goes straight through the island and hung out on the beach. I felt I had to limit it to that, ethically. Sometimes people will take their service animal status to the max, and really push it when it's not necessary.

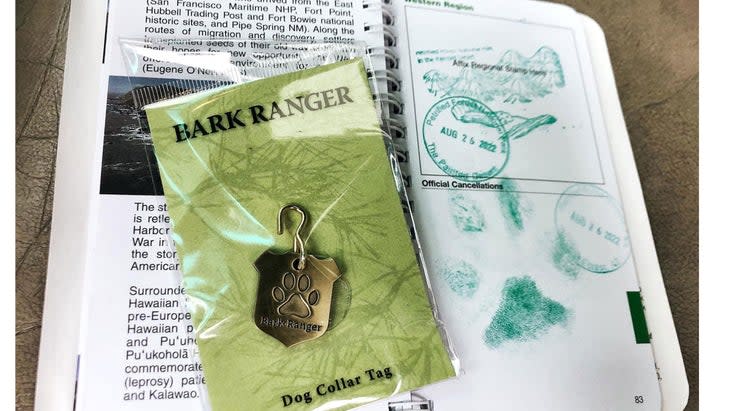

Ranger also has one of those parks passports, and he gets he gets his paw print stamp on his passport at every park as well. Tomorrow after we enter Yellowstone, he'll get his last paw print stamp, and one of the head rangers in the park is going to meet us near Old Faithful for a photo op. After that, Ranger and I are just going to enjoy Yellowstone, keep it quiet and relaxed, and pop a bottle of champagne somewhere.

When my epilepsy hit, and I lost my career, my license, and my ability to live what I thought of as normally, I felt trapped. I think a lot of people with disabilities feel the same way. They feel incapable, or shut off from the world, or like they're in a different category. My message has been that there is no difference. If you want to put your foot out the door and go to all the national parks, there's a way to do it. And there's a way to bring your service animal. All you have to do is make that first move. The only person stopping you is you.

For exclusive access to all of our fitness, gear, adventure, and travel stories, plus discounts on trips, events, and gear, sign up for Outside+ today.