Does Adding Pasta Water Really Make a Difference?

Some people swear finishing pasta with its sauce and some of the starchy pasta-boiling water produces the best result. Others just sauce on top. Who's right?

Serious Eats / Vicky Wasik

There's pasta. And then there's sauce. Put them together and you have dinner. Simple as that, right?

Not exactly.

The thing is, pasta-the-dish isn't just about the pasta-the-starch, and it's not just about the sauce, either: It's about the marriage of the two. And, like all marriages, there are some secrets to getting the union to work. It just so happens that I was recently working on a screenplay on this very theme. Take a look:

SCENE: INT OF A FRYING PAN - DAY

A piece of Penne stands opposite blushing bride Tomato Sauce, whose happy tears have reduced her to an absolute puddle (or maybe it's just her saucy streak). In the pews are hundreds of happy guests, including size-zero aunt Spaghetti and beefy uncle Bolognese, plump grandma Ravioli and wise old grandpa Sage-Butter. Priest Strozzapreti stands between the the soon-to-be-newlyweds, near a font of holy pasta water.

PRIEST STROZZAPRETI: Dearly beloved, we gather here today to witness the joining of Penne and Tomato Sauce in holy macaroni. Do you, Penne, and you, Tomato Sauce, take each other as lawfully wedded husband and wife?

PENNE AND TOMATO SAUCE TOGETHER: Al dente.

- CUT SCENE -

Pixar will totally buy the rights to this script, right? Anyway, the point is that getting pasta and sauce to unite is critically important for the dish to be truly great. The only question is, what's the best way to bring them together?

Most pasta aficionados will tell you that the best way to do it is by finishing cooking the nearly-done pasta on the heat in its sauce with a little of the pasta-cooking water. According to that line of thinking, the starchy pasta water helps to bind and thicken the sauce, and in some cases—such as buttery or oily sauces—emulsifies it into a creamy, non-greasy coating. All of my own pasta-cooking experience supports that theory, but I'd never done side-by-side tests to prove that it actually works better.

The Tests

Test 1: Exploring the Basic Methods

There are three basic ways to cook pasta:

Boil the pasta, then drain it and top it with the sauce

Boil the pasta, drain it, then toss it with the sauce off the heat

Boil the pasta, then drain it (saving some of the cooking water), and then briefly cook it in the sauce with a splash of that reserved water.

The first thing I decided to do was make spaghetti and tomato sauce in three side-by-side tests, to see if one of them was clearly better than the others.

I served each pasta with grated cheese to my colleagues without revealing what I was testing, and asked them to pick their favorite. (Obviously, the pasta that had a puddle of sauce sitting on top was visibly different from the two that were coated in sauce, but otherwise I didn't divulge what I was up to.)

The pasta that had been cooked in its sauce with some of that pasta water won by a landslide. That method bound the pasta and its sauce together in a way the other methods didn't.

As for the other methods, plopping some sauce on top of a pile of plain boiled noodles meant that no matter how much we tried to combine them on the plate, we always ended up with noodles that weren't evenly coated in sauce. Meanwhile, tossing the pasta and sauce together off the heat did a decent job of coating the noodles, but there wasn't the same level of fusion.

Test 2: Getting Starchy With It

Just because our first test demonstrated that it's best to cook pasta in its sauce with some of the starchy cooking water doesn't prove beyond a doubt that the starch itself is important. Maybe cooking pasta in its sauce is all that matters, starchy water or not.

To test this out, I prepared three new batches, with the goal of getting water with different levels of starchiness. I cooked one using the frequently recommended ratio of one pound of pasta (in this case penne) to one gallon of water, to create moderately starchy water. I cooked another following Kenji's recommended low-water method, with one pound of pasta in half a gallon water, which created the starchiest water. And finally, for the control, I cooked a third batch of pasta and paired it with plain tap water. In all cases I salted the water, including the tap water, following our pasta-salting guide.

To make the results as identifiable as possible, I decided to use plain olive oil as the "sauce." As you all know from making vinaigrettes, mixing water and oil is never easy. If starch was going to prove its worth, it was going to have to do a better job of turning plain olive oil into a sauce than the tap water would.

I cooked each batch of pasta until it was just al dente, and then moved it to a pan with olive oil and a quarter cup of the water in question. As the sauces reduced over the heat, the starch's role became crystal clear. The plain salted water formed a thin sauce that was very oily, while the moderately starchy water formed a sauce with a thicker texture but a fair amount of oil on its surface. The starchiest water, on the other hand, formed a sauce that was thick, creamy, and silky, with the least amount of surface oil.

Serious Eats

None of the sauces formed a totally perfect emulsion (that's what I get for trying to make a sauce from nothing more than oil and water), but the starchiest water was by far the most emulsified of the three. A little grated cheese tossed in at the end is all I would have needed to fully bind the sauce.

Bonus Test: The Pasta Matrix, or How to Bend Pasta-Cooking Times to Your Will

So now we have what I think is pretty conclusive evidence that it's not only best to finish pasta by cooking it in your sauce of choice with a little of its cooking water, but that starchier water yields the best sauce. Hopefully most of you are convinced, too.

But I know that old habits die hard. If you're still not on-board, I'm going to give you a choice: Take this blue pill, and you can go on living your pasta life, eating bowls of so-so spaghetti and thinking it's all great. But if you want to know the truth, take this red pill. I warn you, though, your whole idea of what's real may never be the same...

...ah, so you took the red pill (or you're just curious and are still reading—that's fine, too). So, what if I told you that you can bend pasta-cooking times to your will? What if I told you that there's a way to take pasta that typically reaches the al dente stage in 10 minutes and stretch it out so that it takes 12 or 15 minutes? What if I told you that there is no noodle?

Okay, there's a noodle...as far as my noodle can tell, anyway. But you really can change its cooking time, and the way to do it is—drumroll please—to transfer it to the sauce to finish cooking. The earlier you transfer the pasta to the sauce, the longer it will take to finish cooking, because pasta cooks more slowly in sauce (even sauce that's watered down with cooking water) than it does in boiling water. Just take a look at this photo to see what I mean.

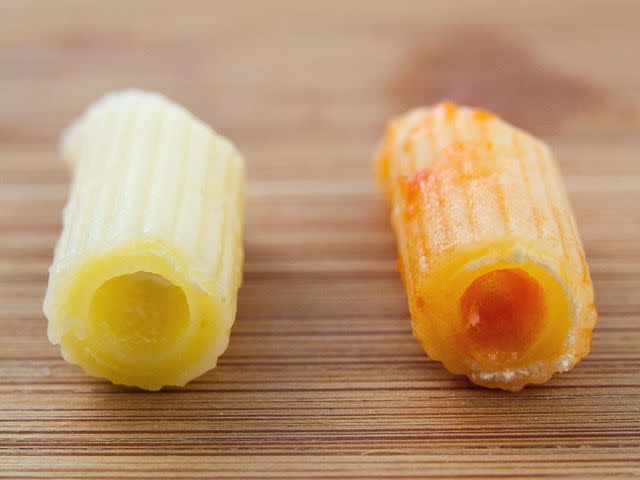

Both the pieces of penne you see came from the same batch of pasta, which I started cooking at exactly the same time in the same pot of salted boiling water. About halfway through the pasta's suggested 12-minute cooking time, I fished out half the penne and immediately transferred it to a pan with some simmering tomato sauce, and cooked them together, gradually adding ladlefuls of the pasta-cooking water, much like making risotto. Here's what happened:

At the 10-minute mark, the pasta in the pot was al dente, and the pasta in the sauce was underdone.

At the 12-minute mark, the pasta in the pot was tender, while the pasta in the sauce still hadn't reached the al dente stage.

By the time 14 minutes had passed, which is the stage shown in the photo, the pasta in the pot was nearly overcooked, while the pasta in the sauce was just reaching al dente (note the white ring of uncooked pasta at the core of the one on the right).

This is what I like to call Pasta Bullet Time, a state where pasta on the verge of being overcooked suddenly slides into a slow-motion crawl to doneness, buying you time to finish cooking the chicken that isn't quite done, or dress and toss the salad that you totally forgot about. Now you have the power!

Conclusion

If you want your pasta to have a long, happy marriage with its sauce, it's best to cook them together with a little of the pasta-cooking water. Plus, that method reduces the chance of overcooking the pasta, since the pasta cooks more slowly once it's simmering in its sauce.

Just one bit of caution when cooking pasta in its sauce: Because the pasta-cooking water is salted, there's a risk of the dish becoming too salty if you keep adding and reducing ladlefuls of it. Keep tasting the pasta and sauce as you cook them together—and switch to adding plain unsalted water if the pasta needs to cook a little longer but already has enough salt.