In a New Documentary, a Lens Into Robin Williams’s Beautiful Mind

Early on in Robin Williams: Come Inside My Mind, Marina Zenovich’s new HBO documentary, we hear a snippet of unsourced audio. “Do you have any fears?” asks an interviewer. “I guess I do have a fear,” admits Williams, “that if I felt I were becoming not just dull, but a rock, I still couldn’t spark, then I’d start to worry.”

It’s a devastating bit of footage, knowing what we do now: that Williams, a fearless, brilliant, irrepressible performer whose brain sparked at dizzying speeds—“he was like the light that never knew how to turn itself off,” the stand-up comic Lewis Black observes on camera—eventually met the very fate he feared. In 2014, following a roller-coaster decade—alcoholic relapse; divorce; massive heart surgery; third marriage; mysterious medical symptoms; tepidly received sitcom (The Crazy Ones)—the actor and comedian, 63, committed suicide. The story of his death, as reported in the media, shape-shifted as quickly as the rubber-faced Williams in a typically supersonic medley of bits. He had gone back to rehab. He had been depressed. He had been diagnosed with Parkinson’s. No, the autopsy revealed, actually he had diffuse Lewy body dementia, a related form of degenerative neurological disease with symptoms including hallucinations, anxiety, and cognitive deterioration. “Toward the end he looked like a wax figure,” his Mork and Mindy costar Pam Dawber remembers. “His brain was giving him misinformation,” another friend, comedian and director Bobcat Goldthwait, explains. In death, as in life, Williams had a mind with a mind of its own.

A few years after his passing, inspired by the massive public response, Zenovich began work on her film. The director, whose prior credits include documentaries about Richard Pryor and Roman Polanski (two, actually, on the latter: the first inadvertently helped authorities reopen the case against him; the second tracked the aftermath), soon caught wind of another Robin Williams project in development from Alex Gibney, a friend and mentor. The pair merged their films, joining forces through Gibney’s production company, with Zenovich staying on as director and Gibney coproducing. That collaboration has yielded a sensitive, impressionistic look at Williams’s meteoric rise to fame: from his lonely, well-off childhood in suburban Detroit; to his high school years in freewheeling late-’60s Marin County, where the Williams family eventually moved; to Juilliard, where he honed his craft; to the heady mid-’70s Los Angeles stand-up scene, where he made his name as both a comedian and a partier (somewhere in there he picked up a bad cocaine habit). Williams earned a reputation as a nimble, virtuosic performer whose stand-up operated more like a one-man show. “We knew whatever it was Robin was doing, we weren’t going to get close to that; all we had was our stupid little jokes,” remembers David Letterman. On stage he would move through impressions and characters and jokes and accents so quickly and with such lightning-fast reflexes—honed through improv training—that he could sometimes appear a man possessed. Eventually he landed a role as a kindly, clueless alien on the ABC sitcom Mork and Mindy, a star vehicle that eventually launched him to Hollywood leading mandom (with some missteps along the way, including a bizarre turn as Popeye in an ill-fated Robert Altman musical adaptation).

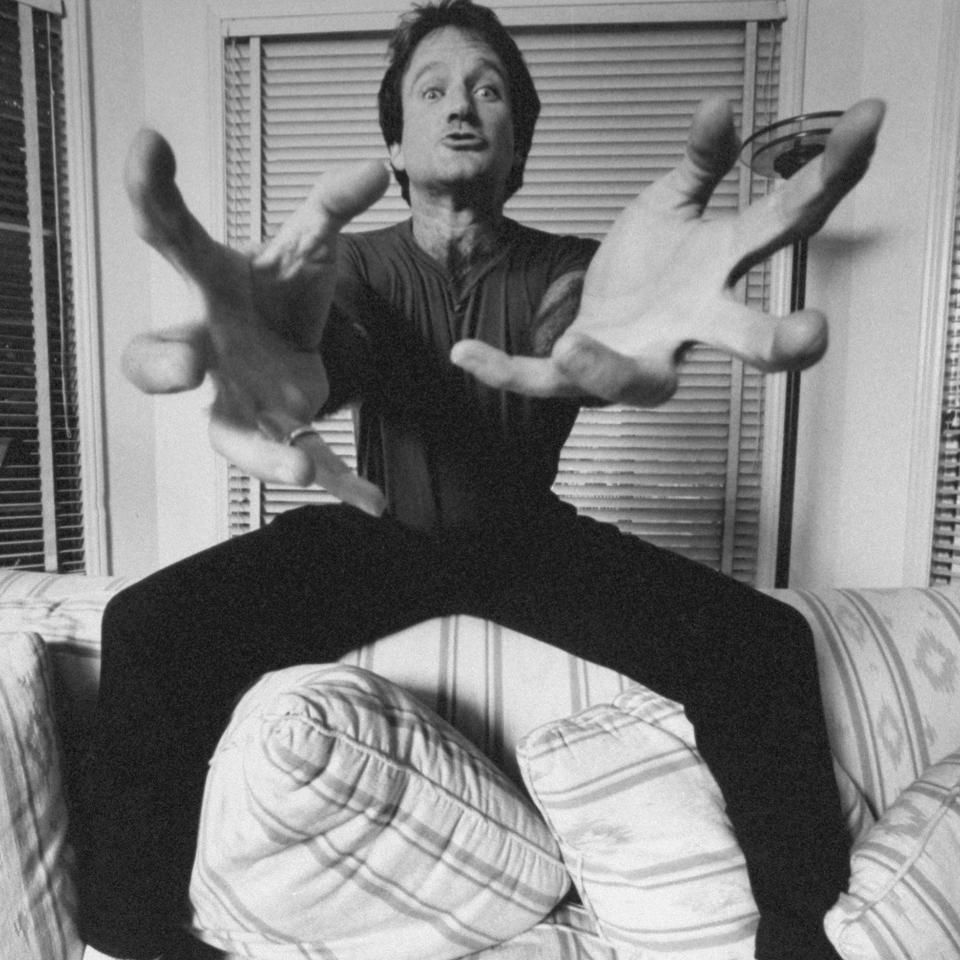

Zenovich casts video footage of Williams’s manic stage persona, including plenty of B-roll from his various TV and film projects, against found audio interviews that reveal the comedian’s quieter side. A portrait coalesces of a man far more complex and less cuddly than those of us in the Mrs. Doubtfire generation may have imagined: Williams offstage was as withdrawn as onstage he was vivacious. “If you met him during the day you’d never know what he became at night,” the comedian Elayne Boosler recalls. He was an addict, through and through, with performing eventually emerging as his drug of choice. “There’s a real incredible rush when you find something spontaneous,” he observes in one clip. “I think your brain rewards that with a little bit of endorphins. If you think again, I’ll get you high one more time.”

A few months ago The New York Times reporter Dave Itzkoff published Robin, a biography of Williams that references much of the same material—interviews, anecdotes, stand-up sets—used in the film. Itzkoff’s deep dive presents a far fuller picture, and an even darker view, of the comedian’s early years: his drug use, his womanizing, his tendency to absorb material from other comedian’s sets and repurpose it in his singular way. It makes for enlightening companion reading. But what Zenovich’s film lacks in comprehensiveness (by necessity: It runs two hours, to the book’s 500-plus pages), it makes up for in dazzling, show-not-tell examples of Robin being Robin. And it’s that, ultimately, that gives the most insight. Speaking about his book in an interview conducted last May with the podcast Recode, Itzkoff pretty much made the same case: “There’s nothing like the experience of just watching him perform,” he admitted. “It says it all. It tells you everything you need to know.”

I spoke with Zenovich about making her film, the hunt for archival footage, and the “insane talent” of the late, great Robin Williams.

You made a documentary on Richard Pryor several years ago, and I believe you interviewed Robin Williams for that. Did you know you wanted to make a movie about him back then?

I was supposed to do that interview but I was deathly ill with the flu that day and couldn’t fly. My producer went and did it. I can still remember being on the couch, being so disappointed. She came back with an interview that we used, but I never met Robin and that was that.

I think all documentary filmmakers are always looking for interesting topics or people. I was a fan of Robin’s growing up. I’ve always loved watching him. I knew how much he was loved, but really I had no idea how much until after he died. When our trailer came out the reaction was unbelievable. I really feel that people feel like he belonged to them.

I’m 34 and I feel like I only really knew a sliver of his career. I had my own Robin Williams, but it wasn’t the whole picture. I imagine lots of people will feel that way. What was your version of Robin before making this?

One of the best compliments I got from someone who saw the film was: I didn’t like him as an actor until I saw your film. I think he got pigeonholed, typecast. He just got into playing the same role over and over again. And he was so much more than that. I watched Mork and Mindy growing up. I knew him from that. I remember seeing Moscow on the Hudson. I saw his other movies, but to me he was Mork. I never saw him perform live. I knew he was talented. But what I think the film shows is where he came from. It shows this immense talent. You get this sense of what he was, which is so much more than what you saw in some bad movies. I remember him in Nine Months as the doctor with Hugh Grant and Julianne Moore. These were roles he was dying to do just so he could play. He was so much about playing. I think people think he was so much about stand-up, but he was an actor actor. Body training. Vocal training. It was serious, to get into Juilliard. Plus he did improv, which is something completely different than stand-up. I love the journey of seeing this insane talent just bubbling out of this man.

It really impressed me how much knowledge went into his jokes. He had this incredible array of historical and literary references at his disposal.

That was something I kept saying in the editing room. He was so smart, so well read, so curious about the world, and so knowledgeable. You can’t make jokes about history without knowing history. I think he was always reading, always feeding his mind. He had this kind of insatiable need for knowledge, and an ability to kind of play with words, you know? So it was great to show where that all came from. I think a big moment for him that really changed his life was when his family moved to the Bay Area. We often wondered what would have happened if he stayed in Detroit. Would he have become just a funny guy working somewhere? It was great for him to go to a place where he could be who he was. He went for it.

In the film there’s a real tonal difference between the sort of manic video footage of him performing and the audio snippets that form a sort of sober, reflective voiceover backbone. Do you think he was better able to access that mode when there wasn’t a camera around? Where did the audio come from?

We were really looking for the emotion. I didn’t know how easy it would be. For Richard Pryor, he told really deep, dark stories that were funny. For Robin, his funny was all over the place. We were really trying to get into his soul and his mind. I didn’t know what we would find. We lucked out because Larry Grobel did two Playboy interviews with him and saved all the audio tapes. We got those. Most of them you could hear. We took lines from that. We used an NPR interview he did. We got an interview he did back in the ’70s. This gentleman had reached out to him, wanted to film him, but didn’t. But he had audiotaped him.

I wouldn’t say it was a conscious choice to show the difference. I think you can see the difference just because he was almost like two different people when he was performing and when he wasn’t. A couple of people told me he didn’t really talk when he was with just one other person, but if a third person came in, he turned it on. Then it was an audience. I think he gave such an enormous amount of energy when he performed. As his first wife said, he had to come home and recharge.

But we really looked for those lines that showed vulnerability, sometimes from audio interviews, sometimes buried in video interviews that had more resonance when you just heard the voice. His first wife put us in touch with Bennett Tramer, who was one of his early friends in the ’70s and wrote with him. [Tramer’s] wife Sonya took a lot of pictures, and they provided some home movies. It’s always a journey, what you’re going to get, who you’re going to get, what you’re going to say. I think that’s the reason it’s scary to make documentaries, and with each one you feel like you’re doing it for the first time again. There’s certain things that come into the editing room that save you. We had a lot of moments like that.

We get to hear voicemails that Robin left his friend Billy Crystal. Were you surprised that Billy was willing to share those?

Oh my god, I was thrilled! I chased them down for months, because I was told Billy had them. But it took awhile for him to get them to me. I was scared he wasn’t going to deliver. And then one day I got those messages on my phone, like, are you kidding me? I just can’t even believe it when I watch the film. They’re so meaningful. It’s so touching that he saved them. They’re so funny. You get a sense of how much fun they had.

You treat the details of Robin’s death, which was widely reported on by the media, with a certain amount of respectful distance. Talk to me about that decision.

Well, it was something that I didn’t know how we were going to handle. And I wanted to have his closest friends talking about him. I didn’t know what we were going to show. We were going through all his movies and trying to find moments when he was by himself, contemplating life, and we found it in this clip from Being Human, 1994, where he’s on the beach. For me, there’s something about his expression in that moment. It kind of changes. He’s looking out out sea, and then he makes this little look, closes his eyes.

Making a film about someone, you have to be respectful. I’m not known for making sensational films, though maybe some would disagree in regards to my Polanski film. (That was not my intention. I followed my nose and ended up making a film about a case that ended up reopening the case, and taking up 10 years of my life making a follow-up film.) It was a difficult moment to tackle, but I feel like it works. I once made a short film about Julian Schnabel, and he talked about found objects. He made some of his art with found objects, his Plate paintings. I feel like when you’re making a documentary it’s almost like you have found objects. You have the interviews you have. How people were that one day when they talked to you. You have footage, archive you’re working with. Hopefully you have enough and it resonates.

Robin’s son Zak and his first wife Valerie participated in this. So did his half brother McLaurin. The rest of the family—his two younger children and second and third wives—did not. Did you know from the start how much access you were going to have?

I tried to meet Susan [Schneider Williams], his third wife. I wanted to meet her when I was in the Bay Area and she didn’t want to meet me. I can’t tell you why, other than it was too soon. The film was made with the estate. His manager David Steinberg had gone to Alex Gibney and wanted to make a film, and I was making a competing film and we merged our projects. So David was very helpful to us, in terms of getting friends to speak. I reached out to Valerie myself. You call people, they get a read on you, and decide if they want to talk. Marsha Garces Williams, his second wife, didn’t want to take part. I would have loved to have had Marsha and Susan in the film. They didn’t want to. At a certain point you make peace with that and move on, represent them as honestly and respectfully as you can. I was excited to talk to Zak. I felt that he was incredibly well spoken. I read about him and saw he was doing interesting things with his life. I appreciate that Zak was thoughtful enough to understand he should be in it. It was a tough interview to do.

It’s always hard. I’ve had people come up to me after I’ve made films and say, “I wish I took part.” Everybody makes peace with whether they do or not. The film, although it’s quite personal, it’s mostly about Robin’s early years and his creative process. It shows his family but I don’t know what everyone could have said. I feel like we covered it without them.

This interview has been condensed and edited.