Discover Booth Pond, a hidden haven for rare dragonflies and damselflies in RI

NORTH SMITHFIELD – Booth Pond and the land surrounding the small, out-of-the-way body of water could have been swallowed up by urban sprawl or simply abandoned.

But land trust volunteers, environmentalists and others fought for 20 years to protect the pond, where rare dragonflies and damselflies breed and a variety of birds and wildlife call home.

Their efforts have resulted in a 132-acre preserve, wedged between big-box stores, parking lots and apartments on one side and a steep granite ridge on the other. Birders, hikers, trail runners and dog walkers follow paths around the pond, through woodlands and wetlands and up a hillside to a rocky outlook with a sweeping view of how the area developed.

“It’s been one long saga,” said Carol Ayala, treasurer of the North Smithfield Land Trust.

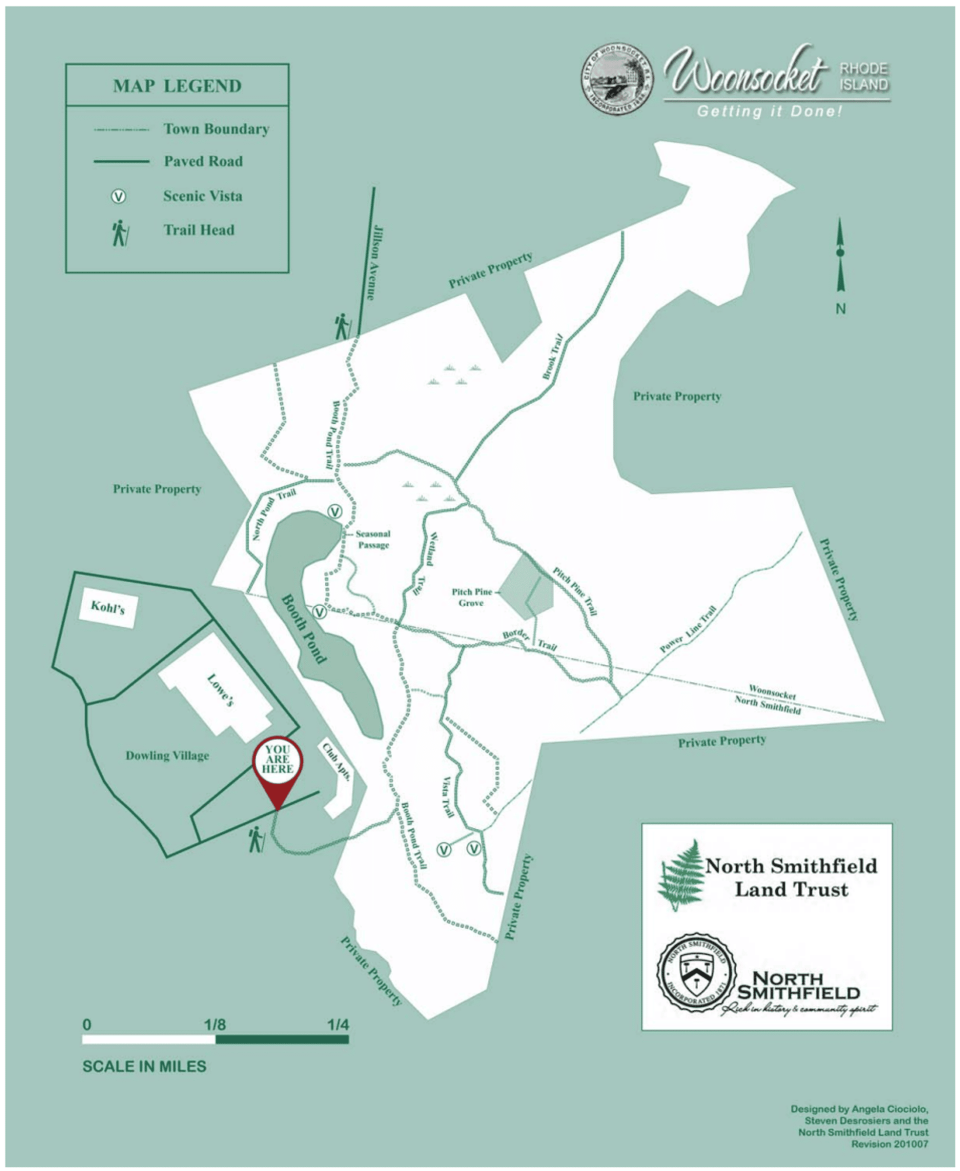

I set out for the preserve on an early March morning with two hiking buddies from a parking lot at The Club at Dowling Village apartments. At a kiosk at the trailhead, I learned that the Booth Pond Conservation Area includes 42 acres jointly owned by the North Smithfield Land Trust and the Town of North Smithfield and an adjoining 90 acres owned by the City of Woonsocket.

We started on a grassy path that curled downhill and passed drainage holding ponds, a granite block wall supporting a parking lot and power line towers before turning left into the woods below the apartments.

The well-marked trail then rises over a small hillock for a first look at the southern tip of narrow Booth Pond. We followed a muddy path with a few puddles to the water’s edge.

Protecting the land from development and trash incinerator

Across the pond at the top of a steep embankment, we could see through the trees a round, white water tank and the rear walls of Kohl’s department store, Lowe’s home improvement center and the apartment complex.

Developers built up the area after a master plan was created in the early 2000s to turn most of the forestland along Route 146A into a huge complex of retail stores, restaurants, condos and other businesses. At one point, there also were plans for a regional trash incinerator and other projects on the Woonsocket side of the property.

However, preservationists, environmentalists, small business advocates and others organized, signed petitions, filed lawsuits and spoke out at town council and planning and zoning meetings to shrink the scope of the developments, save the ecologically sensitive land, safeguard the drinking water supply and create a public preserve for passive recreation.

Eventually, they succeeded in winning concessions from developers, reducing the footprint of the projects and securing some acreage for protection.

The northern section of the preserve was acquired by Woonsocket in 1977.

In 2014, the land trust purchased the preserve for $925,000 with a $400,000 grant from the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management and $525,000 from the town’s open space fund. Even then, it took more work to win an easement on the land from a developer and cut and blaze the trails before the preserve could open to the public.

After thinking about all that history, we followed the edge of the pond through an area labeled “seasonal passage” on some maps because the trail follows a dirt road that dips below the level of the pond. There’s a curious impoundment on the left that may have been built to hold back the water in the pond. More recently, beavers have lodged logs, branches, twigs and mud on the top of the impoundment to raise its depth.

Some water has managed to trickle through the dam to form wetlands and a stream that flows north, part of the watershed of Woonsocket’s drinking water reservoirs. Downstream, hikers report finding an old foundation that may have been a residence or a small mill.

Why is the pond so popular with dragonflies and damselflies?

We circled the northern side of the water to a huge outcropping that gave us a good look at the pond – a type of depression in the land called a fen that catches rain and runoff from the hillsides. The pond has also provided habitat for rare species of dragonflies and damselflies.

Virginia Brown, a conservation biologist and author of “Dragonflies and Damselflies of Rhode Island,” did an inventory at Booth Pond about 20 years ago and documented more than 50 species of dragonflies and damselflies, including the ringed boghaunter, Rhode Island’s only endangered dragonfly.

During the debate over Booth Pond, she testified before municipal and state boards about its value as a wildlife habitat.

Are conditions at Booth Pond deteriorating for dragonflies and damselflies?

In a recent interview, Brown said an aide visited Booth Pond a couple of years ago for a research project and found that over the years the pond has been degraded as a natural sanctuary.

She explained that once there were no fish in Booth Pond, which made it an ideal larval habitat for dragonflies and damselflies because fish are a natural predator. But she recalls seeing somebody dumping fish in the pond, and if they have multiplied, they probably have gobbled up some species of dragonflies and damselflies.

Also, the beaver activity (we spotted many tree stumps gnawed to a point, a beaver lodge and a dam) has significantly raised the water level. Dragonflies and damselflies lay their eggs on shallow, boggy shorelines with sphagnum moss and on floating vegetation on open water. The raised water level has inundated the habitat at Booth Pond, making it less inviting to dragonflies and damselflies.

Finally, the commercial development that replaced the forested landscape around the pond created runoff, including pollution and siltation, that has affected the temperature and quality of the water, she said. Also, while dragonflies and damselflies spend most of their lives in water as larvae, the insects do emerge to forage in upland forests, most of which have been cut down around the pond.

Brown suspects that the endangered dragonfly and two others that the state had listed as “greatest conservation need” have been lost, as well as many other species she identified 20 years ago.

She said, however, that it’s also possible some new species live there now. Any dragonflies and damselflies would be most visible in late April, May and June.

What other wildlife are you likely to see at Booth Pond?

While the habitat for dragonflies and damselflies has been damaged, there are still signs of life. Hikers report seeing deer, fishers, red foxes, turkeys, groundhogs, opossums, racoons, skunks, rabbits, squirrels, chipmunks and a variety of birds.

Melissa Alexander, a birder from Blackstone, frequently visits the preserve and has spotted and heard many spring migrating birds, such as Eastern towhees, prairie warblers, blue-gray gnatcatchers, field sparrows and wood ducks.

She said the preserve provides the birds with a safe spot among all the commercial development and parking lots to feed, breed and nest.

After a long look at the pond from the outcropping, we continued along the bank, passing some stone walls that may indicate the property was once farmland. One report I read suggested the name Booth Pond may have derived from the Booth family who lived in the area in the 1800s, but I couldn’t confirm that.

When the path started to run uphill toward the property line, we turned, retraced our steps and followed an old road that led to a junction and another road that ran north to Jillson Avenue in Woonsocket.

We decided to go straight and headed southeast on an old cart path as it climbed a steep hillside covered with oaks, maples, beech and hickory trees. Side trails on the left ran north to private property.

An oasis of pines and pond in the midst of retail sprawl

The trail narrowed to a footpath, with some loose stones, and then passed through a 1-acre pitch pine grove, with pine cones on top of pine needles creating a soft path. Just before the trail reached an opening for a string of power lines, there’s a granite marker at the border of North Smithfield and Woonsocket with a “W” on one side and an “NS” on the other.

The power lines run across a ridge and then downhill to the right by the apartment complex. From an outcropping high above steep ledges, we looked west and could see lined, blacktop parking lots and big-box stores, including Walmart, Aldi, Lowe’s, PetSmart and Kohl’s, as well as the apartment complex.

In the distance, across Route 146A, a hillside is covered with solar panels. Down below on the right, Booth Pond is hidden in the trees.

Plans to expand the preserve to 240 acres

We followed a yellow-blazed trail across the strip cleared for the power lines into a 114-acre parcel that the town has purchased and that will expand the preserve to about 240 acres.

The path turned downhill, passed some wetlands with patches of skunk cabbage and looped back to the trail below the apartment complex where we had started. We returned to the trailhead after walking 2.4 miles over 90 minutes.

At the kiosk, we met Paul Soares, the land trust president, who was resupplying maps. He had participated in the long fight to save the land and helped cut, blaze and maintain the trails. As Booth Pond evolves, he says, they’ve won some fights and lost others, and there’s always more work to do.

But the mission hasn’t changed: preserve an ecologically sensitive pond and surrounding habitat while providing passive recreation for the public.

That’s a worthy goal.

If you go …

Access: Off Route 146A headed north, take a right on Dowling Village Boulevard. After the Aldi store, take a right on Booth Pond Way. The trailhead is on the right.

Parking: Four designated spots in a parking lot.

Dogs: Allowed but must be leashed.

Difficulty: Easy on wide paths with some climbs up a ridge.

GPS Coordinates: Trailhead: 41°58’44.15″N, 71°30’21.44″W

Lectures and signings for 'Walking Rhode Island' book

John Kostrzewa’s book, “Walking Rhode Island: 40 Hikes for Nature and History Lovers with Pictures, GPS Coordinates and Trail Maps,” is available at local booksellers and at Amazon.com. He’ll sell and sign books after the following presentations:

Monday, April 29: Osher Lifelong Learning Institute at URI, 10 a.m. Registration required at tinyurl.com/a3srcux5.

Wednesday, May 15: Walking for Your Health, with Dr. Michael Fine, William Hall Library, Cranston, 6:30 p.m.

Thursday, May 23: Greene Public Library, Coventry, 6:30 p.m.

The Walking Rhode Island column runs every other week in the Providence Sunday Journal. John Kostrzewa, a former assistant managing editor/business at The Journal, welcomes email at johnekostrzewa@gmail.com.

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: Booth Pond is a haven for rare dragonflies | Walking Rhode Island