Dior’s Couture Diplomacy

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below."

Last March, shortly after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the Kyiv-based artist Olesia Trofymenko received a message from a curator friend of hers, Solomia Savchuk. Dior, the bastion of French couture and ready-to-wear for 75 years, which has been under the creative direction of the Italian designer Maria Grazia Chiuri since 2016, wanted to commission Trofymenko to make a large-scale artwork for the Fall 2022 couture show in July. “It was a little bit unreal,” Trofymenko tells me, “because it was the first month of war and a really hard time and hard, painful news. So it was like a message from another reality.”

Chiuri knew it was a long shot.

“I believed it was just a little bit impossible,” she recalls. But she badly wanted Trofymenko involved in the show. “I was worried that we might forget what has happened,” Chiuri says. “Because all these images that we see every day, the risk is that we believe that is normal.”

After several starts and stops, Trofymenko landed on a hopeful image: a series of embroidered paintings of the Tree of Life.

It’s a symbol “that is part of Ukrainian culture, but it is also a part of the culture around the world, of different religions,” says Chiuri. She sees putting art together with the craftsmanship of couture as a way to connect distinct but overlapping cultural aesthetics and traditions. “I think in fashion, [this] is a moment [that’s] really difficult and complex, because the world is changing so much and everybody has closed themselves in their comfort zone,” she explains. “But fashion and art and creativity are a way to build a bridge.”

Chiuri has at times been criticized for the social messaging of her collections, with some saying that her more overt feminist overtures have rung hollow. But these bridges, as she calls them, are a distinct phenomenon in fashion. At the quintessential French fashion house, which also happens to be one of the most financially successful in the world, Chiuri is sharing her platform with other female creators across the globe and proclaiming that their artistic output is just as rich, worthy, and complex as anything that comes from France.

Dior’s fall couture collection was made up of mostly neutral-hued dresses and skirts embroidered with arabesques and plant life that reflected Trofymenko’s concept. Right before the show, the artist recalls, Chiuri told her, “The fashion world has some rules and limitations, but it has much more viewers than the fine-art [world]. That is the reality. And we can focus a much bigger audience on this problem.”

“It was a great responsibility for me to show our Ukrainian culture and to be one of the Ukrainian voices for such a big [audience] of people,” Trofymenko says. “I hope I nailed it.”

THE FASHION WORLD IS RIFE with team-ups between artists and designers, musicians and designers, and even designers with other designers. But Chiuri’s collaborations still feel original because they are ambitious (like a Spring 2020 couture collaboration with Judy Chicago, a vocal fashion skeptic) or unorthodox (menswear designer Grace Wales Bonner created just one look for the Resort 2020 collection) or nearly impossible to pull off, like this project with Trofymenko. (Even when we spoke in the late summer, Trofymenko found it safest to connect via WhatsApp, and the artist communicated with Dior mostly through Savchuk until shortly before the show.)

These partnerships are, most of all, heartfelt, driven by what Chiuri believes she can do with the power and resources of one of the world’s biggest fashion houses rather than what might be on trend or surprising for the moment.

When we speak, it’s about a week following the couture show; Chiuri appears on-screen from her office in Paris in a simple black T-shirt and black jacket, her eyes thickly rimmed with her signature black eyeliner. Her expansive white desk is pristine and uncluttered. I suggest to her that there might be something particularly feminine or feminist to her collaborative approach. Chiuri’s style of leadership feels more like sharing the stage, giving equal credit to those who work with her, than macho credit claiming. “I think that to work with other people is an enrichment. I am not narcissistic,” she says with a wry smile.

To open the spotlight like that reflects a certain confidence. “I was also lucky because I arrived [at Dior] when I was 52, so with my different maturity, I want to give my [knowledge] to the new generation,” Chiuri muses. “I’m very proud when I see in my studio that the young designers grow up and they are more talented than me. I’m really proud of it.”

The fashion world is still ruled primarily by male creative directors making clothes for women. Valerie Steele, the fashion historian and director of the Museum at FIT in New York, says that Chiuri’s leadership at Dior is distinct for this reason alone. “She talks about how it isn’t just a question of how women look but a question of how women feel in the clothes,” she says. This fall, the museum’s Couture Council honored the designer with its award for Artistry of Fashion. Steele is continually struck, she says, by how Chiuri’s “commitment to working with women artists and women photographers just seemed like such a really empowering thing to do, not just a performative thing to do.”

Chiuri likes female artists—and more specifically ones who make works that incorporate handicrafts, like embroidery or textiles. “I think in the past, this kind of craftsmanship was closer to this idea of domestic life and not celebrated like art,” she says. “I really believe that it’s a form of art.”

And critically, she does not believe that fashion is simply a French art. The mythos of couture has always insisted that it is something inherently French, that the French understanding of silks, embroideries, beadwork, and construction is superior. Chiuri has worked to dismantle this myth and suggest a more globalist view. “I think that this idea to think only in France there is couture—it has no sense,” she says. French couturiers have had artisans from other parts of the world make their embroideries for decades; a tag that reads “Made in France” often obscures the fact that the embroideries were made in India.

Chiuri’s Spring 2022 couture show, for example, was a celebration of the work of Chanakya, the Mumbai-based embroidery house that has been a backbone of the fashion industry since it was founded in 1986 by Vinod Shah. (His children, Karishma Swali and Nehal Shah, now run the business along with Shah’s wife, Monica.) But Chanakya is rarely mentioned in the fashion world because of prejudices that suggest that real fashion—the kind that walks the runways—should come from European workshops. Swali and Shah’s company, Chiuri says, “has the same knowledge of our première in Paris because it’s also part of their culture. Textiles and embroidery are present throughout the country, and you can find excellent [examples] everywhere.” Chiuri forged a public partnership with the house’s School of Craft, whose students are women from low-income communities, working with them on her Spring 2020 and Fall 2021 couture presentations. Foregrounding their work once again in the Fall 2022 show made it clear just how significant she believes their work to be.

“I really want to explain that the storytelling is different,” Chiuri says. “We are stronger [if we] promote it.” A few years ago, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, the writer whose book title We Should All Be Feminists appeared on T-shirts in Chiuri’s debut collection, in 2016, took her to a fashion show in Lagos. “This creativity,” she says, reflecting on that trip, “I think it is everywhere.”

That idea that creativity is everywhere may sound like a platitude, but it strikes me as quite radical. Christian Dior is a name that is synonymous with Frenchness. His New Look—a cinched-waist jacket with a gobsmacking full skirt and a saucer hat—was introduced in 1947 and was quickly embraced as an embodiment of femininity and patriotism after the ravages of World War II. It celebrated the superiority of French craftsmanship, French ideals of beauty, and the exquisite, incomparable French technique of making clothes. The global economy, spun into being by a global supply chain, where much of the world’s clothes are produced in the Global South, has complicated that story. Many fashion brands seem not to acknowledge these changes—including, until Chiuri’s arrival, Dior. So to sit at the front of the most quintessentially French house and say that other countries can make clothing at the level of couture? It’s a provocative declaration.

Chiuri credits her daughter, Rachele Regini, who is 26, with yanking her view of fashion into the modern world. Rachele went to college in London, and when she returned, “she was very critical of the fashion system,” says Chiuri. Rachele and her brother, Niccolò, talked to their mother about cultural appropriation and the industry’s impact on the environment. It resonated deeply and forced the designer to acknowledge the industry’s complexity: “It’s always a personal dialogue to explain to them the real value of the fashion system.” Often, fashion observers see just a single picture. They may not realize, the designer explains, the number of people all over the world who contributed to that one look. “Because it’s a big community. It is really teamwork. But we live in a time where you have this idea that behind the creative director, behind the design, there is nobody. That’s not true.”

When the fashion world was thrown into crisis by the pandemic, Chiuri took every precaution to stage a resort show in July 2020 in her native Italy so that her employees and the artisans she worked with wouldn’t be out of a job. “Sometimes there is an idea that fashion can be the solution to all the problems of the world. It’s not true.” She laughs. “We can work seriously, with real attention. But we have to think very hard about what we say.”

CHIURI IS RIGHT THAT FASHION is frequently asked to do too much. Too often, designers today freight their work with purpose that the clothes simply cannot carry or may not even reflect. In her first few years at Dior, the clothes themselves often had political messages, like that famous feminist T-shirt, or a collection celebrated the Linda Nochlin essay questioning the lack of renowned female artists (“Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?”). The approach, in recent years, is less heavy-handed; explaining the craftsmanship is the focus. Chiuri usually styles her models in flats, and the clothes remain simple, often austere, in muted colors. The effect is that in the Fall 2022 couture collection, for example, Chanakya’s embroidery comes to the forefront, and that, along with the message of Trofymenko’s art, becomes the story.

What women love about Chiuri’s clothes is that she has put a brand once known for its vibrant fantasticalness, particularly under John Galliano in the mid ’90s to early 2010s, in conversation with their lives. “She has made the brand really relevant—really, really relevant,” says Christine Suppes, a fashion collector and Dior customer who has consulted with museums including the de Young in San Francisco and the National Museum of Women in the Arts (NMWA) in Washington, D.C., which honored Chiuri last spring. Suppes is drawn mostly to the hourglass dresses that derive from the New Look. “They pack beautifully,” she says. “She’s thinking always of her client. I just take them out [of the suitcase], shake them a little bit, and put them on the hanger. I’ve worn her clothes all over the world, and they’re so relevant.” Dior’s earliest designs were constricted and clearly designed for a woman who traveled with a flotilla of steamer trunks. But Chiuri’s clothes look as much at home in Dubai, Suppes says, as in Washington, D.C. “She has managed to fold the New Look into her look,” she says.

Steele recently visited the newly opened Dior museum at the brand’s refurbished Paris flagship and was struck by the contributions Chiuri has made in only six years to an oeuvre that includes pieces by Galliano, Raf Simons, Yves Saint Laurent, and Marc Bohan. “You’re seeing the history of the brand, and I think she’s already made a very significant contribution to the reputation of what Dior is and can be,” she says. Go to any hotel lobby in the world and it wouldn’t be surprising to find women of all ages wearing her ribbon slingback flats, updated Saddle bags, and feminist T-shirts.

For a client like Suppes, though, the political messaging is neither here nor there. “I’m not going to wear a T-shirt with a political slogan on it,” she says. It’s the craftsmanship that speaks more to her. Of Chiuri, she says, “She has really taken Dior, with the codes of the house, into the 21st century, utilizing the best of the embroidery.” For the NMWA gala, Suppes wore a richly embroidered dress covered in flora, and she emphasizes how it was “so beautiful, but very wearable.”

Steele recounts a similar experience wearing one of Chiuri’s designs, her update of the Bar jacket, for the Couture Council luncheon in September. “I was kind of stunned,” she says. “I don’t know what she’s done with it, because I’ve seen ’50s jackets and they’re not as flattering and empowering to wear.”

“That’s part of the liberation” of Chiuri’s Dior, Suppes adds. “And that’s part of her liberated fashion view.” HB

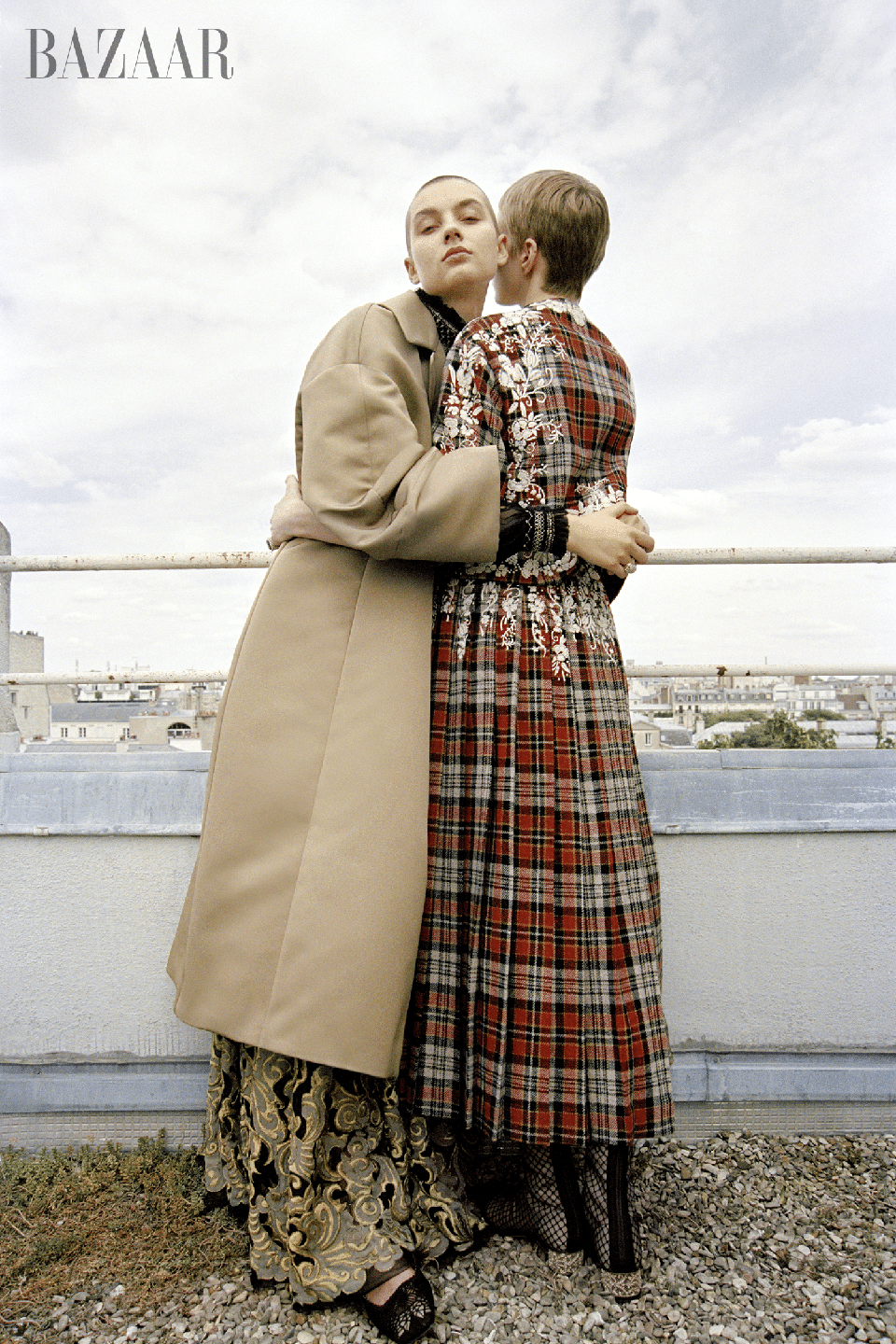

Opening Image: Maria Grazia Chiuri. Clothing and accessories, her own.

Models: Freja Rothmann and Sylwia Kuta; Hair: Olivier Noraz for Oribe; Makeup: Stephanie Kunz; Manicures: Anais Cordevant for Manucurist; Production: Ben Faraday at Octopix.

This article originally appeared in the October 2022 issue of Harper’s BAZAAR, available on newsstands October 4th.

You Might Also Like