‘Diego Rivera’s America’ at SFMOMA a Reminder That Art Matters

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In this summer of record heat, inflation and political turmoil, “Diego Rivera’s America” has arrived at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art as a reminder of why art matters.

With more than 150 paintings, drawings and frescoes, some recreated through wall projections, the museum calls it the most comprehensive exhibition of the Mexican activist artist’s work in 20 years.

More from WWD

Inside 'Another Justice: Us Is Them' at the Parrish Art Museum

"Diego Rivera's America" at San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

A Look at 'Fashioning America: Grit to Glamour' Exhibition to Bow in Bentonville

Organized thematically, the show highlights the development of his figurative style, how he imagined Mexican identity, celebrated the essential workers of his day, and the technological achievements of the Machine Age.

“Rivera’s vision was fundamentally in opposition to art for art’s sake,” says guest curator James Oles. “He was thinking about how art might matter beyond the individual…as a tool, or he would say a weapon to transform society. Or at least get us to be more empathetic with the working class and with the daily grind, even of a woman making tortillas or selling flowers in the market, and to be more respectful of racial difference, particularly in a country like Mexico.”

The exhibition focuses on the 1920s to the 1940s, when Rivera returned from Europe to Mexico and was hired to paint murals in public buildings as part of reconstruction after the Mexican Revolution.

He joined the Communist Party and began documenting the Indigenous people of Tehuentapec in rural Mexico. Based on observations of their daily life he painted idealized portraits of the working class, including women doing domestic work, in paintings such as “The Tortilla Maker” (1926), “The Flower Carrier” (1935) and “Woman With Calla Lillies” (1945), many of which were acquired by wealthy art collectors.

©2022 Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F./Artists Rights Society (ARS), NewYork; photo:The Art Institute of Chicago / Art Resource, NY

Although his paintings were not overtly political, “Rivera felt they could have a short- and long-term impact in changing people’s sensibilities,” Oles says. “He was more interested in shaping the perceptions of what today we’d call the influencers. In other words, the artist doesn’t change society directly but can change society by changing the attitudes and prejudices of the people who ultimately shape society, whether they are school teachers, government bureaucrats or administrators, or wealthy industrialists.”

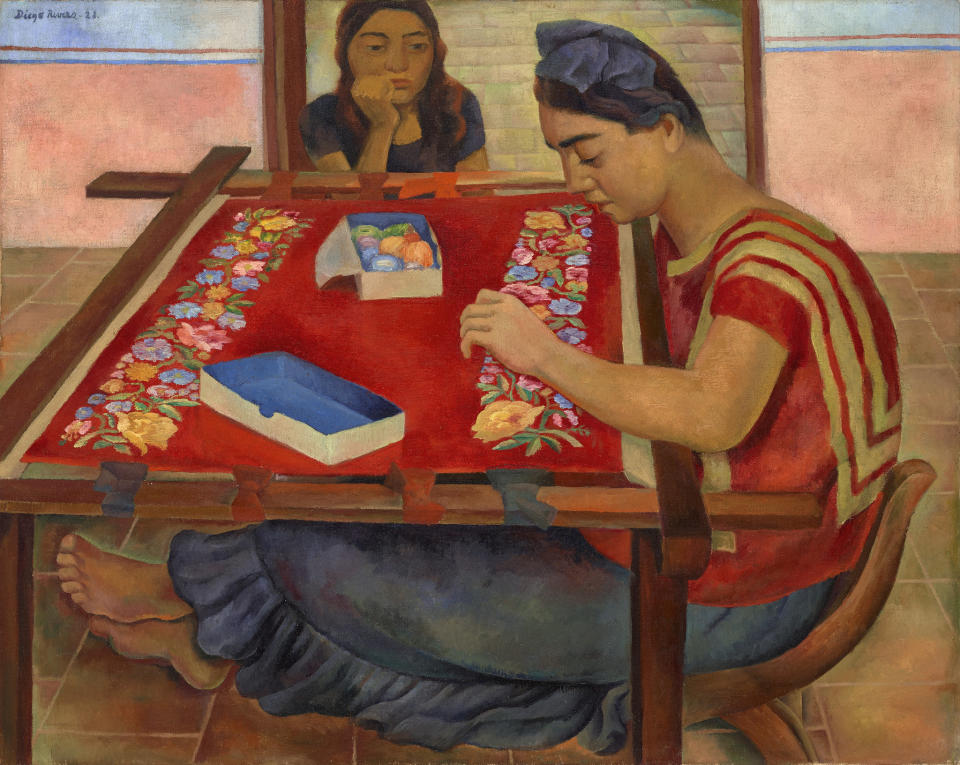

One of the most stunning paintings, “The Embroiderer” (1928) — which features a woman working intently on a colorful floral embroidery, and a second female figure looking on — has never been seen before in public. It was also the hardest to find, Oles says. Because there was no reliable catalogue of Rivera’s works, he only had black-and-white photos from old publications to go on, which he sent around the world to auction houses, dealers and art historians to try to locate the missing painting.

The only thing he could find out was that it was in New Orleans, but where remained a mystery until last year, when he got a call from Christies New York, explaining that the family that owned the painting for multiple generations was putting it up for auction. The Museum of Fine Arts in Houston bought the work, then lent it to SFMOMA for the show.

©2022 Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F./Artists Rights Society (ARS), NewYork; photo: ©2022 Christie's Images Limited

During the 1920s to ’40s, Rivera also traveled to the U.S., completing some of his best known and most politically charged works amid the economic collapse of the Great Depression, including the frescoes he made for the Detroit Institute of Art and for Rockefeller Center in New York, with funding from two of the wealthiest families in America: the Fords and the Rockefellers. Both frescoes are represented in the exhibition through drawings and wall projections.

He included a portrait of Communist leader Vladimir Lenin in the Rockefeller Center mural, which created such an outcry among some members of the Rockefeller family and other critics that Rivera was asked to remove it. When he refused, he was forced to leave the U.S.

Rivera traveled to San Francisco on several occasions with Frida Kahlo, who has three paintings in the show. He was commissioned by the Pacific Stock Exchange Luncheon Club to paint “Allegory of California” in 1930, depicting the wealth of the state, and the workers and industry that generated it. The mural is represented in the museum in a projection, but can also be visited on a guided tour of the location downtown.

In 1940, he created “Pan American Unity” during the Golden Gate International Exposition on Treasure Island as 30,000 spectators watched. On display in the museum’s first floor, the 10-panel fresco weaves together North and South American history, picturing revolutionaries like Abraham Lincoln and Miguel HIdalgo along with Aztec gods, inventors Henry Ford and Samuel Morse and Mexican laborers, and referencing the war gathering in Europe with the faces of Adolf Hitler, Benito Mussolini and Joseph Stalin, next to scenes of Charlie Chaplin in “The Great Dictator.”

“He wanted to see America as a place of creativity and innovation distinguished from Europe, and to believe America was still a place of unlimited possibility to be connected to the past and the modern technological future, a place that shared a spirit of independence with Mexico,” says Oles, pointing out the impact Rivera had on other muralists working under New Deal programs, as well as contemporary Chicano and Latine artists. “He thought art mattered…and we need those visionaries to prompt us today.”

“Diego Rivera’s America” is on view at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art through Jan. 2.

Launch Gallery: "Diego Rivera's America" at San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

Best of WWD

Sign up for WWD's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.