Did a Soviet Spy Really Work for Queen Elizabeth II? The Answer Is Complicated

Season 3 of Netflix's The Crown finally premiered on November 17.

During the first episode, "Olding," we're introduced to a new cast that includes Helena Bonham Carter as Princess Margaret, Tobias Menzies as Prince Philip, and Olivia Coleman as Queen Elizabeth II.

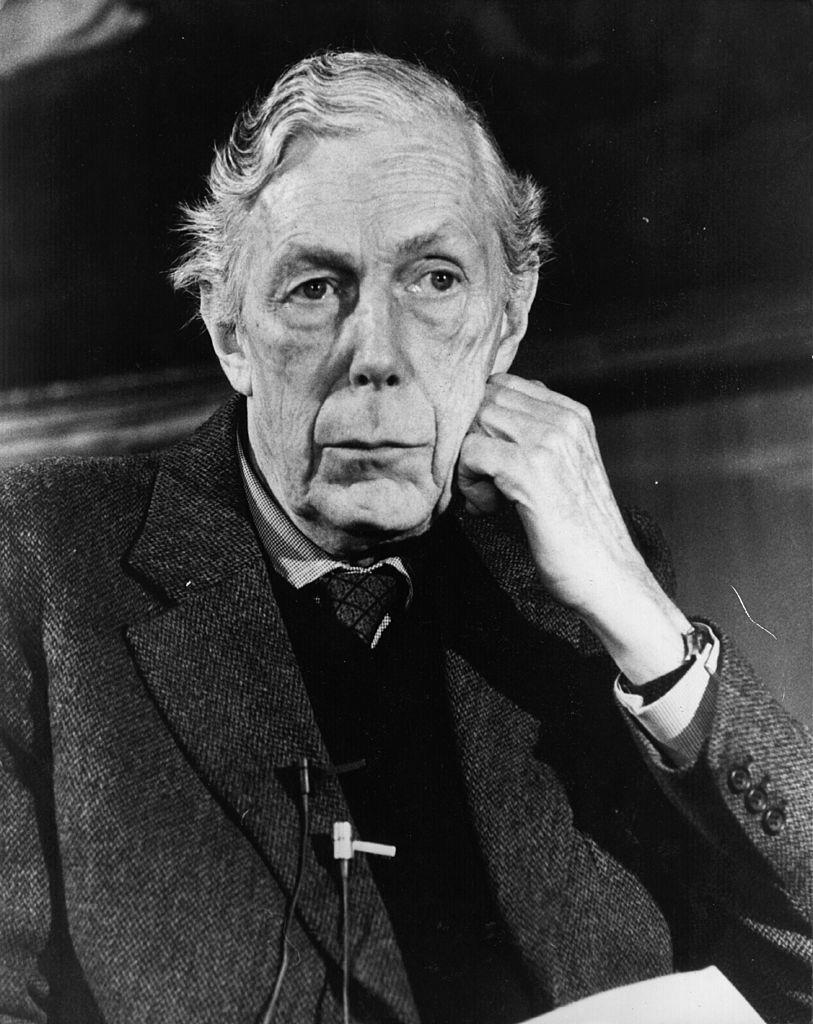

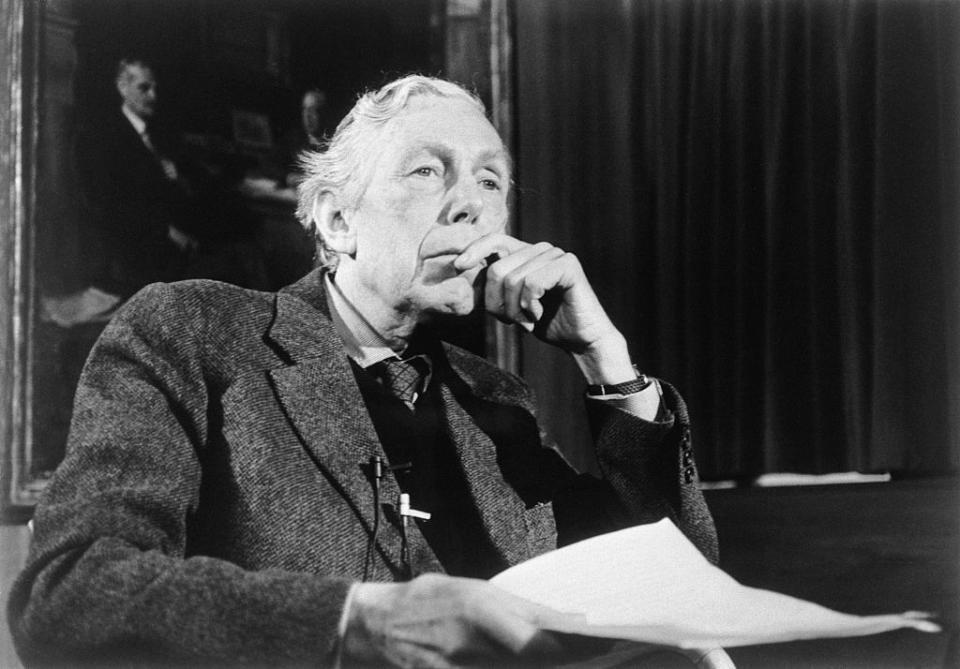

We also meet Anthony Blunt (Samuel West) who we soon learn is a former Soviet spy turned royal art curator.

So what really happened between Blunt and the royals? Warning: spoilers ahead!

During The Crown's long-awaited season 3 premiere episode, "Olding," we were finally treated to the magic that is Olivia Colman as beloved monarch Queen Elizabeth II. But as we marveled at her performance, we couldn't help but be shocked by the storyline she commands: that of a World War II spy employed at Buckingham Palace.

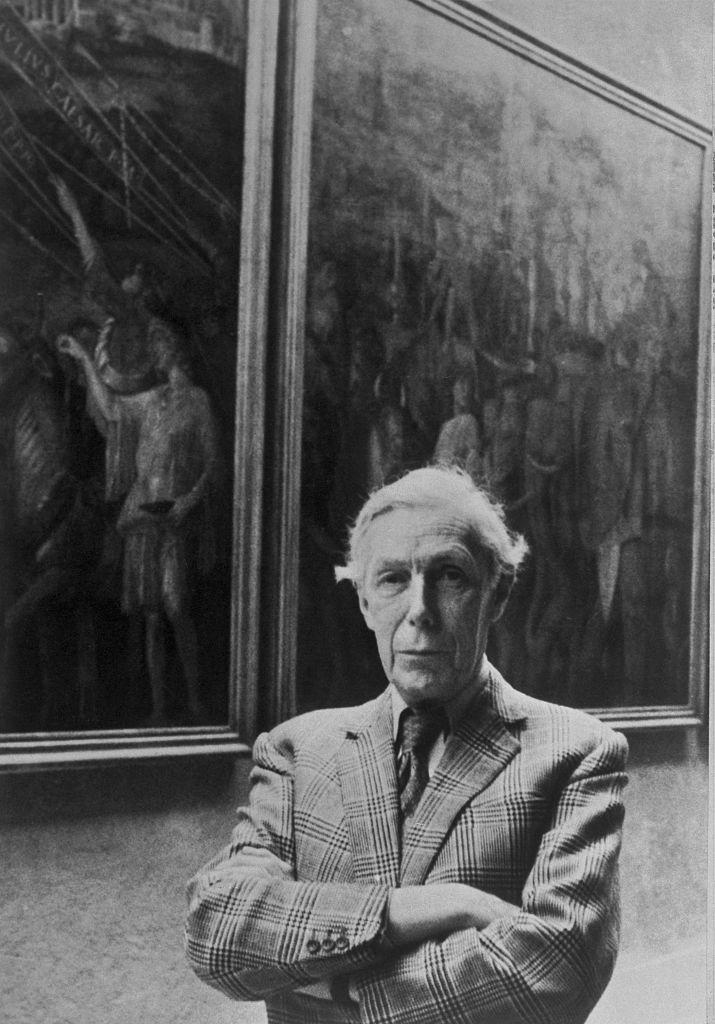

Despite dramatic depictions on the Netflix hit, the story of Anthony Blunt (Samuel West) is anything but fiction. Blunt served as the royal's official art curator—a.k.a. the Surveyor of the King and Queen's Pictures—for 29 years, working for both the queen and her father, King George VI. The celebrated art historian was even the Queen Mother's third cousin and awarded a knighthood in 1956.

But despite his shining public persona, Blunt had a nefarious past that soon comes to light in "Olding," as it's revealed he betrayed his native Britain and served as a Soviet spy both during and after World War II. In the first episode's closing credits, producers left us with the below message:

"Anthony Blunt was offered complete immunity from prosecution. He continued as surveyor of the queen's pictures until his retirement in 1972. The Queen never spoke of him again."

We delve into the true story, below.

So what's all this about Anthony Blunt being a spy?

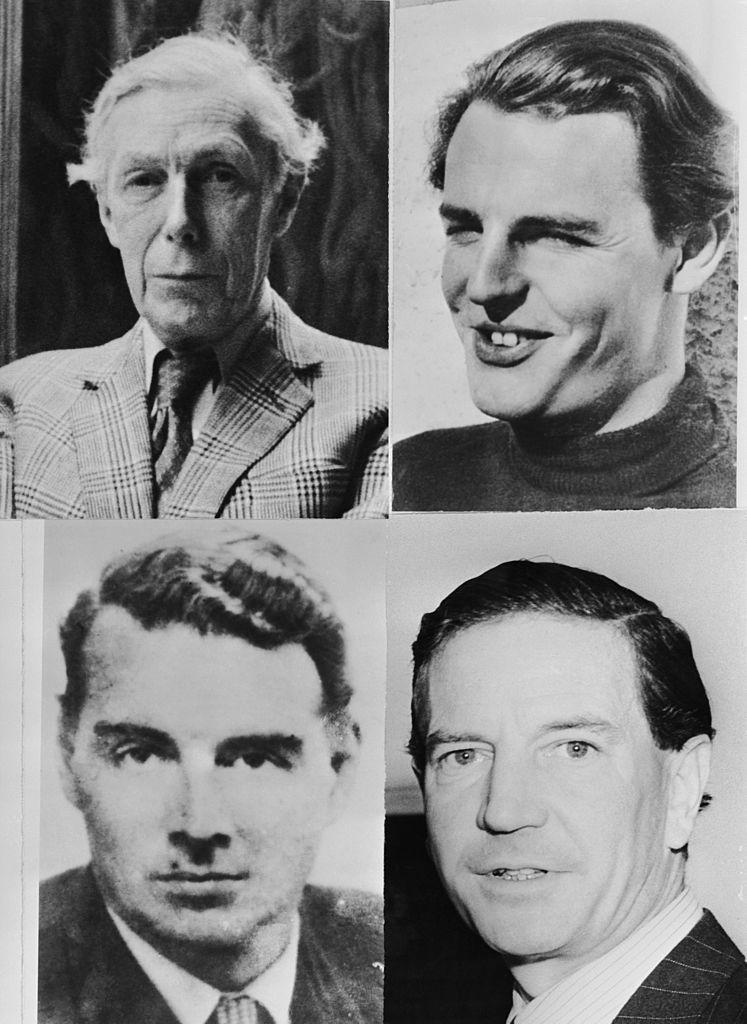

According to Encyclopedia Brittanica, Blunt was recruited into what is now known as the "Cambridge five spy ring" while he was a fellow at Trinity College, Cambridge in the 1930s. The group was made up of upper-middle class young men who, in contrast to the philosophy of their native British government, were attracted to ideals of communism and anti-fascism. They were led by U.K. diplomat Guy Burgess, who according to The Telegraph, persuaded Blunt to work for the administration of Joseph Stalin—the Soviet Union's communist leader.

During World War II (1939-1945) Blunt worked as a high-ranking agent for Britain's intelligence agency, MI5, while covertly maintaining his work with the Soviets. He recruited fellow spies for them and also passed on private information to Russia (a German ally) that he learned as a U.K. official, per The New York Times.

In 1945, Blunt became Surveyor of the King’s Pictures, and in the years that followed he served as the director of the Courtauld Institute of Art and an art history professor at the University of London. But even in the post-war years, he'd still communicate with Russia, passing on information he learned as a member of the royal household. He even helped Burgess and Donald Maclean—another Cambridge spy—escape to the Soviet Union in 1951 when their espionage was about to be discovered.

Was his discovery as dramatic as it's depicted in The Crown?

In the premiere episode of season 3, Blunt's whistleblower (American Cambridge spy recruit Michael Straight) turns himself in at the Department of Justice in D.C., and the Director General of MI5, Furnival Jones, reveals Blunt's betrayal to Colman's Queen Elizabeth II. Then, while giving a lecture, Blunt is interrupted by British intelligence, who take him in for questioning where he confesses to his crimes and being the "fourth man" of the spy ring.

While we can't confirm the sensationalism of these events, it seems the producers of The Crown (as always) took creative liberties in depicting how it all actually went down. In 1963, Straight did indeed confess to the Americans that he was a Soviet Spy during World War II, revealing Blunt's name in the process. At the time, Blunt was serving as Surveyor of the Queen's Pictures, but fully confessed to being a spy upon authority questioning in 1964. Given that he was a royal employee, the queen was told as well, while the prime minister at the time, Alec Douglas-Home, was not, according to The Guardian.

If the queen knew about Blunt, did the palace keep his activities a secret?

In the show both the queen and Prince Phillip are clearly disgusted by Blunt's actions, but grudgingly agree to not publicly ruin him as to not risk embarrassing British intelligence. Since we don't know what the monarch thought of the situation—she's never spoken on it publicly—the real reason for keeping Blunt's misdeeds hush-hush are a little more complicated.

While The Crown makes it seem as if it were largely up to the royal to decide whether to out Blunt, the truth was U.K. intelligence "granted immunity from prosecution" and job security in exchange for his 1964 confession, according to The New York Times. Consequently, he was able to keep his esteemed status as royal art historian intact, and served as Surveyor of the Queen's Pictures until his retirement in 1974.

"His role at Buckingham Palace carried with it no access to classified information, and it was also decided not to embarrass him in any way that would end his continuing cooperation with the authorities on matters of intelligence," the Times reported in 1983.

Did the public ever find out?

It wasn't until November 1979, The Guardian reports, that Blunt's betrayal against his country became known to the world as it was revealed by Margaret Thatcher during a speech at the House of Commons.

He was quickly stripped of his knighthood as a result, and his reputation was ruined. In response, Blunt issued a statement that read: "In the mid-1930s it seemed to me and to many of my contemporaries that the Communist Party and Russia constituted the only firm bulwark against Fascism, since the Western democracies were taking an uncertain, compromising attitude towards Germany.''

He died at 75 years old in March 1983 and in the years before his death called his actions "an appalling mistake," according to The New York Times.

For more stories like this, sign up for our newsletter.