How Did Carole Baskin Become the Least Popular Figure in Netflix's 'Tiger King'?

Like much of America, I recently binged the hell out of Netflix’s extremely popular documentary series, The Tiger King: Murder, Mayhem and Madness.

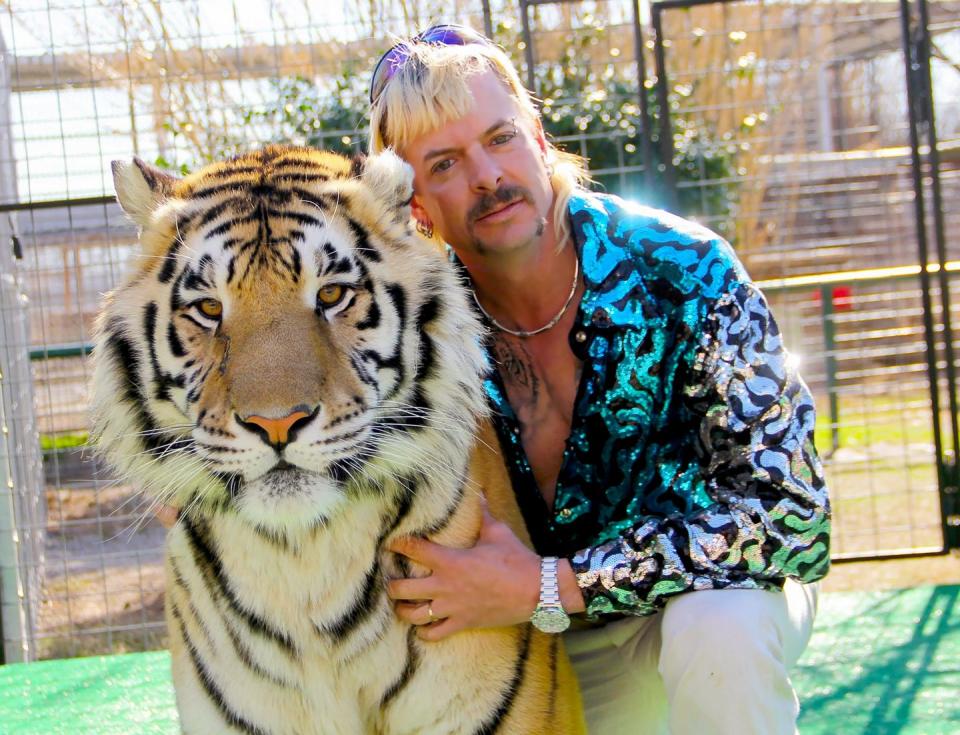

If you’ve watched it, then you’re familiar with the inciting incident of the series: big cat breeder and former zoo owner Joe Exotic (Joseph Maldonado-Passage) is in prison for a failed murder-for-hire plot targeting Carole Baskin, a nonprofit founder and owner of Big Cat Rescue, a sanctuary for wild cats (tigers, lions, etc.) in Tampa, Florida.

Maldonado-Passage chose Baskin as a target due to her consistent attempts to shut down his zoo via both her conservation efforts and lobbying for the passage of the Big Cat Public Safety Act, which would outlaw the new ownership of big cats.

In digging into this real-life feud that sets the series in motion, viewers are given access to three over-the-top figures: Maldonado-Passage, Baskin, and Doc Antle, another breeder who runs his own for-profit zoos where visitors can cuddle with tiger cubs, which were bred expressly for that purpose.

Throughout the series, which was filmed over five years starting in 2014, viewers are exposed to plenty of Antle and Maldonado-Passage’s unsavory deeds in their business dealings. Antle is an egomaniacal Eastern-teachings polygamist whose “wives” serve as his cat trainers. Some people interviewed for the documentary even stated he kills tigers when they’re no longer viable for his business (Antle denies this). Maldonado-Passage’s conviction includes charges for illegally killing five tigers in 2017.

In one of the series’ most disturbing scenes, Maldonado-Passage drags a newborn cub away from its mother—through the dirt and under a fence with a metal rod—in order to prepare it for human interaction. Moments later, he gripes that the tiny tigers, taken from their mother and put in a small cage in his home, are making too much noise. Other depressing scenes follow overwhelmed caretakers as they a) ration an inadequate supply of rejected Wal-Mart meat to feed Maldonado-Passage’s menagerie, or b) pilfer it for themselves because they barely make enough money working in the park to feed themselves. Let us also not forget when a tiger rips the arm off an employee and cameras capture Maldonado-Passage’s apparent lack of concern as he frets aloud about how the accident will affect his zoo’s financial prospects.

But the series continues to be a smash hit, with viewers eager to dig deeper and deeper into this so-bad-it’s-good world. And as many have done just that, Carole Baskin, the animal activist Maldonado-Passage wanted dead, has emerged as the least likable character among the bunch.

While many viewers express warm feelings for Maldonado-Passage—a gay, self-proclaimed redneck who admitted that he’d shoot anyone who tried to take his cats—and Antle, while less admired, still has faced little more than internet ribbing, Baskin blithely biking around her cat compound in a flower crown while an army of volunteers shovel big-cat excrement for her seemed to fill some viewers with fury and contempt. Further, in comparison to Maldonado-Passage and Antle’s more boisterous personalities, Baskin comes off as frustratingly aloof, unshakable, and, at times, blissfully self-unaware.

Then of course, there is Tiger King’s B-plot: the controversy surrounding the disappearance of Baskin’s second husband, Don Lewis. A fellow big cat lover himself, Lewis went missing one night in 1997 and, after initial investigations that turned up little to no evidence for a suspect, red-flags from Lewis's family, friends, and attorney led them to believe Baskin had something to do with his disappearance. The series also explores the conspiracy theory that Baskin ground Lewis up and fed him to her cats.

When I recently posted in a Tiger King Facebook group, half-joking, “How is a woman who probably murdered her husband the most sympathetic of the three?” I was surprised to find Baskin sympathizers in the minority. In fact, tons of Facebook users, more of them women than men, hate Carole Baskin, and they definitely aren’t afraid to say so. They bashed her as a hypocrite who once bred big cats herself (in the 1990s), deemed her “deeply unlikable,” sanctimonious, and a phony who profits from caging big cats despite her organization being a literal and well-rated nonprofit. Some insisted that anyone who fails to see Baskin’s shadiness is naive. One critic said I was “bamboozled” by her, blinded by her disingenuous love-and-light hippie act and “aw, shucks!” nerdiness.

But even if you buy into the unsubstantiated rumor that Baskin murdered her husband, her crimes stack up pretty evenly with those of Maldonado-Passage, at the very least. Tipping the scale in his favor, therefore, seems difficult to do without factoring in the effect of misogyny. A lower bar for men and higher one for women just seems to permeate our culture—we know that.

As she was throughout The Tiger King series, Baskin is dismissed online by many viewers as “that bitch.” But painting the anti-Carole crowd with a broad brush of misogyny probably isn’t entirely fair, either.

A discussion of whether underlying misogyny might help explain the strong audience contempt for Baskin should acknowledge the role of the filmmakers, Eric Goode and Rebecca Chaiklin.

The pair said in a Rolling Stone interview that, rather than investigating wild animal exploitation, they were interested in exploring “the pathology” of animal people and said they had the mockumentary Best in Show in mind while working on the project. In effect, that leads to some artful skimming-over of certain facts. Goode and Chaiklin offer up interview after interview of subjects—most of them men—who rail against Baskin for a laundry list of offenses and then, in response, show Baskin “responding” to these claims with two lines of rebuttal in less than ten seconds clips.

You'd think Goode and Chaiklin would ask and even push Baskin on these issues to get her side on why, yes, she keeps animals in pens (because rescued cats can't be rereleased into the wild, they wouldn't make it), why she charges to get into her park where the animals are not allowed to be touched (it's expensive to care for animals, even at sanctuaries), and why she had a change of heart from when, decades earlier, she used to breed big cats with her ex-husband. And, yet, it just seems like the filmmakers skirt right past these obvious questions because, ostensibly, it would end up making Baskin a more redeemable person. And what’s the fun without a villain on whom we can dump all of our ire?

Baskin, then, was framed negatively—as a grinning, disquieting crazy cat lady—from the moment we see her on screen, says Andrea L. Press, professor of media studies and sociology at the University of Virginia and author of Feminist Reception Studies in a Post-Audience Age.

“Even I didn't like her at first—it was impossible to,” Press says. “First, we’re introduced to the Tiger Man [Maldonado-Passage], colorful and animated and wrestling with his tigers. We’re thrown into his life with imagery that draws you in. Then we meet Carole, shown in this static view giving you statistics, almost like a talking head.”

Even if viewers agree with her, care about big cats, and are able to acknowledge her role in actual conservation, Press says, “It’s hard to have any positive resonance with the way she’s filmed, as an unemotional bureaucrat. It’s like this woman wants to keep us from having fun. Why doesn't she go away and make dinner so we can play in the backyard?”

Of course, Press says, viewers can certainly be swayed to adopt certain viewpoints, but we do participate in the process of drawing conclusions from the media we consume. During that process, men are often and more easily seen as likable. Press offers serial killer Ted Bundy as an example: Among his legions of fans was the judge in his case, who lamented in open court what a shame it was that Bundy threw his potential away because he would have been a great lawyer.

But it’s a tough topic to study, she says. We don’t have a patriarchy-free society to serve as a “control group” when we consider whether audiences judge women more harshly than men.

“We can’t reduce the norms of the patriarchy to only media representation,” she says. “They’re embedded in all our institutions. But we need to start unpacking some of these biases because they hurt women.”

I asked Press why she thought so many people seem unwilling to at least do a two-second Google search about some of the negative charges against Baskin, such as what the cages at Big Cat Sanctuary are really like, whether her rescue has a good rating, or even to find out more about the disappearance of her husband before bashing her online.

“What we’re living through now is mass distrust in the media,” she says. “ I’m not sure how much people believe that they can ever know the truth about anything. People had this emotional image [of Joe Maldonado-Passage] presented to them in this show, and they’ve come to really like this guy, against rational thinking.”

In effect, Press says The Tiger King dramatizes some of the problems we're having in this country.

“People don't take time to evaluate issues in depth,” she says. “They just want to rationalize and look at cool images, especially now, when we’re all looking for escape. What better way to escape than wrestling with tigers?”

Virginia Pelley is a freelance journalist and essayist based in Tampa, Florida. She has written for The Atlantic, The Washington Post, Cosmopolitan, Glamour, VICE and The Daily Beast.

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY

You Might Also Like