Dickens' A Christmas Carol remains a classic 180 years later. Did it also change holiday?

LONDON — Marley was dead, to begin with, and 180 years later "A Christmas Carol" has transformed the holiday we celebrate this week.

Originally published in 1843, Charles Dickens' novel of a bitter, solitary miser's metamorphosis into a warm-hearted soul remains not just one of the most popular holiday traditions but one of the best-selling and most-adapted works of fiction. Even a book about the making of the classic was made into a movie.

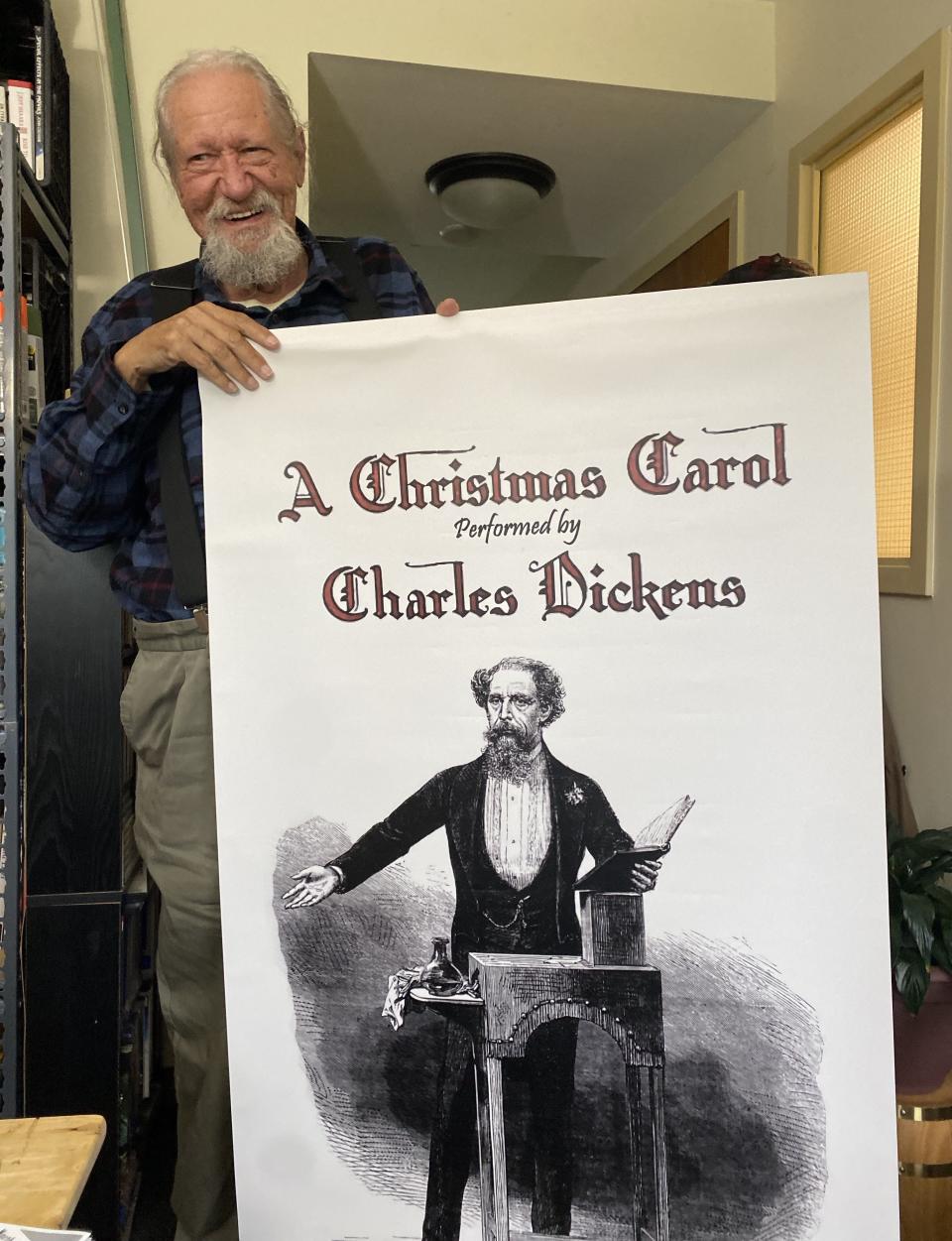

Les Standiford, author of "The Man Who Invented Christmas: How Charles Dickens' Christmas Carol Rescued His Career and Revived Our Holiday Spirits," argues that "A Christmas Carol" launched the modern holiday that is celebrated today.

"It was purely a religious holiday without any secular trapping," said Standiford, a professor at Florida International University. "Dickens reinvented Christmas, the modern Christmas we know today."

That is open to debate, but certainly Dickens' classic is a holiday staple, and nowhere more so than in London, the city in which Dickens wrote one masterpiece after another, including his homage to yuletide goodwill and celebration.

This walking tour of 'A Christmas Carol' in Dickens' London is a performance, too

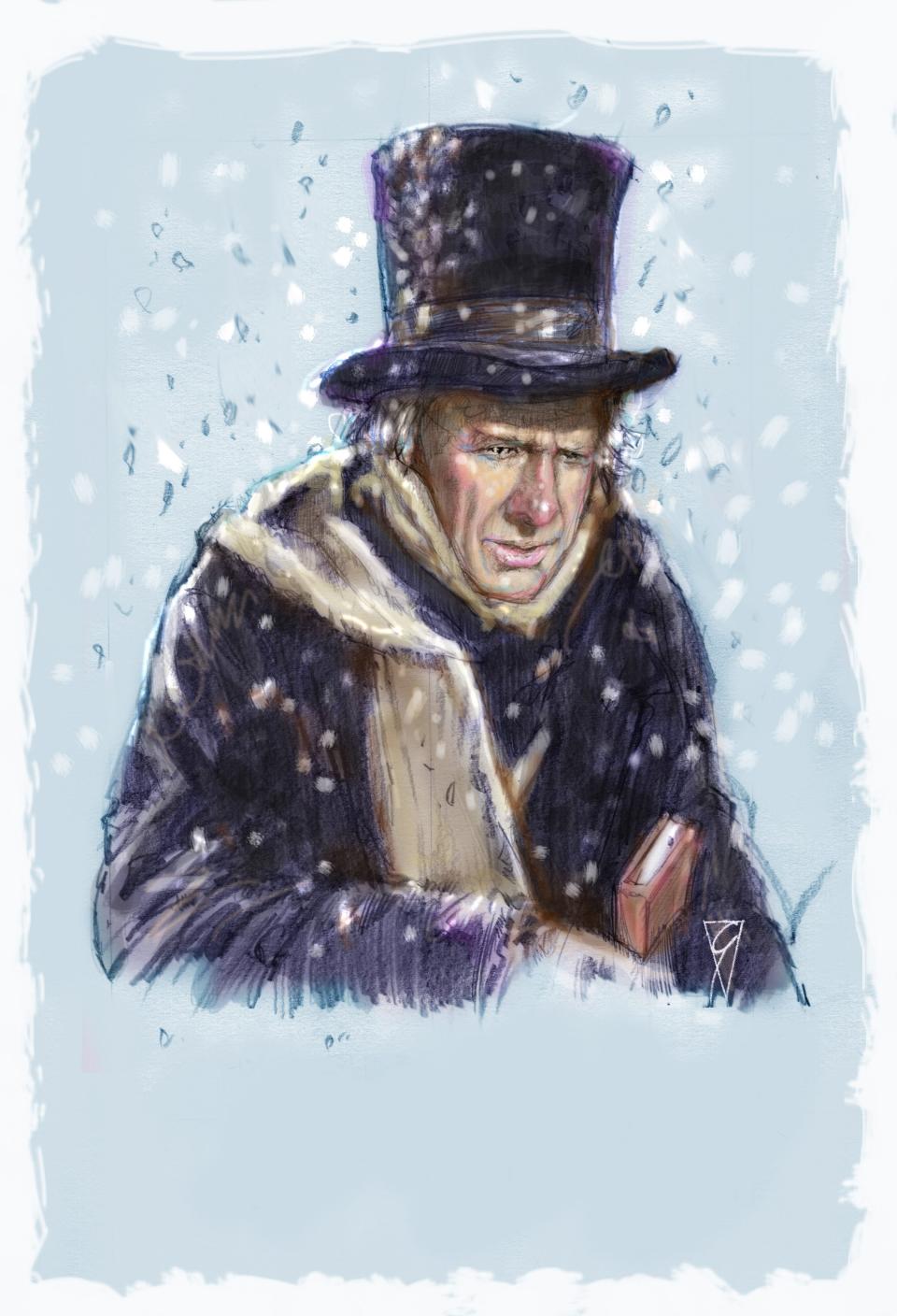

Dressed in a stove pipe hat, violet ascot and charcoal cloak, tour guide and Dickens aficionado Richard Jones said the classic is one of the "most loved, best known, most filmed, most performed" Christmas stories.

Jones, in fact, was readying to deliver a quasi one-man show of Dickens' short story as he guided about 50 tourists and locals along a two-hour walk winding through the city's financial district. During the excursion, Jones recited passages from the 85-page story with the flare of a Victorian-era actor, noting that "A Christmas Carol" was intended to be acted out.

"The wonder of 'A Christmas Carol' is it's a book not to be read, it's a book to be performed," he said. "That's why it's called 'A Christmas Carol.' That's why it is in musical staves, and not chapters, because it's a performance piece as opposed to a thing to be read."

This Jones-led trek began at a square across from the Bank of England and stopped at numerous places mentioned in the novella, such as Cornhill ward, as well as locales sleuthed to have inspired Dickens, like the "melancholy" George & Vulture pub, and whereabouts such as Leadenhall Market that Jones concedes he included out of "artistic license."

Throughout, Jones interwove tidbits about the book, including that it either created words used in language today or gave immortality to colloquial expressions of the mid-19th century.

An example is the term "scrooge" for someone who is a callous skinflint, which was coined from the last name of the protagonist in the story, Ebenezer Scrooge. Jones noted how Dickens decided on the last name Scrooge by combining the words "screw," as in to cheat someone, and gouge. The expression "bah, humbug" for a party-pooper, Jones explained, conjoins the word bah, a synonym for dismissive, and humbug, which meant a fraud.

He spiced the presentation with citations from the book in which Dickens indicted socio-economic theory and policy of the period that was heartless toward the poor ― the working class laborers whose toil enriched the very upper classes that dismissed them as "surplus population."

More about foreign Christmas celebration Nativity scenes haven't changed much. Has their meaning? How some say Christmas display can unite

Jones' performative excerpts of dialog from the book included an exchange between Scrooge and his nephew, Fred, as well as a riveting rendition of a final scene with the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come. He notes a subtle detail — the trembling hand of the Grim Reaper-like Ghost of Christmas Future that foretells how Scrooge would manage to save himself via his own repentance.

As he concluded, the four dozen or so who witnessed the recital and stroll through Dickens' London clapped exuberantly as if they had watched a theatrical play in the West End district. "A Christmas Carol" is a deserving masterpiece, to be sure, Jones said, and it is astonishing that Dickens wrote it in a couple weeks longer than Christians today celebrate the Advent season.

"The amazing thing about it is he wrote it in six weeks," said Jones, noting the story was first published on Dec. 19 and all copies were sold out by Dec. 24, Christmas Eve.

London sparkles at Christmas time in lighted and colorful displays

Few places celebrate Christmas with the resplendent splendor as Dickens’ London. The British capital glittered again this December for the 180th anniversary of "A Christmas Carol" with stunning light and ornamental displays.

In Covent Garden, giant golden bells and red baubles hang from the arched roof over the Apple Market. Walking further west, in the Piccadilly Circus theater district, lighted stars shine above the pedestrian walkways and sparkling angels hang above the Regent Street luxe shopping district while icicles with stars dangle above Oxford Street.

London’s iconic pop-up Christmas markets abounded throughout the city selling trinkets, jewelry, fish and chips and even churros dusted with cinnamon. Carol concerts were performed in numerous churches and concert halls, and a children’s choir sang seasonal favorites at King Charles and Queen Camilla’s Windsor Palace state room.

At the Museum of Natural History, a life-size animatronic Tyrannosaurus rex wearing a Santa hat and holiday sweater — and answering to "Santa Claws" for the holidays — delighted children at the entrance to the dinosaur hall. A Christmas tree brought cheer to the seriousness of the museum historical exhibits in the tunnels that were Winston Churchill's World War II bunker, the War Room.

At the Tower of London — the notorious prison and execution yard — holiday trappings included Christmas trees with pewter and gold decorations that bookended the marker at the spot on the green where Henry VIII’s second wife, Anne Boleyn, was beheaded.

Near Russell Square, four stops on London's subway, known here as "the tube", from where Jones began his tour, is one of the houses Dickens inhabited. Nearly two centuries later, it is a museum and like so much of London, is decked out for the holidays.

A Christmas wreath is hung on the brick, three-story rowhouse's iconic bright red front door. In the dining room, holly adorns a grandfather clock, the fireplace's mantle and the portrait of Dickens in his youthful years. While those are seasonal decorations, to be sure, quotes from "A Christmas Carol" also line the walls of a nursery along with others from Dickens' classics owing to the importance the holiday story has in Dickens anthology.

Why 'A Christmas Carol' was Dickens' gift to the literary world — and himself

It is, in fact, hard to underscore just how critical a gift "A Christmas Carol" delivered to Dickens' literary career, and his acclaim as one of England's literature masters.

In the year or so before he wrote it, Dickens experienced a series of serious professional setbacks that landed him in a financial crisis and triggered a morose sense of professional doubt and uncertainty.

His travelogue on a journey through the eastern United States, "American Notes for General Circulation," was a bust that came across as a resentful indictment of U.S. society and may have cost him the friendship of Washington Irving. Then his sixth novel, "Martin Chuzzlewit," fell way short of sales expectations.

As a result, FIU's Standiford said Dickens found himself "broke and ready to quit writing" as publishers of his previous blockbusters, "The Old Curiosity Shop" and "Nicholas Nickleby," "turned him down flat" when he approached them with new ideas.

Dickens thought about quitting the novelist career and moving to the European continent, Standiford said.

"In essence 'A Christmas Carol' had almost never come to be," he added. "'Christmas Carol' has sold more copies than any other book in the English speaking world besides the Bible, it's been said, and it almost didn't get published. It wouldn't have if not for Dickens' belief in his own material."

That belief was born in a visit to Manchester, where he spoke to a working-class audience. It was that evening's speaking engagement that sparked a renewed mission, and "A Christmas Carol."

"All of a sudden he realized, I think, that he had gotten up on his high horse and was talking down to his readers instead of trying to forge a connection with them, the thing he had always been good at," Standiford said. "During the course of that speech, that's where he reconnected with the passions that led him to his early success ... It was almost revelatory. A spiritual conversion if you will."

And in the process, he renewed a holiday perhaps as well.

Did Dickens' Christmas Carol 'reinvent' Christmas?

Standiford said the novel did not supplant the underlying Christian celebration of the birth of the messiah, Jesus Christ.

But, he said, it broadened its appeal by emphasizing the faith's message of philanthropy, goodwill and kindness and attaching it to the holiday. Or, in the words of Scrooge's "dead as a doornail partner," Jacob Marley, he made "charity, mercy forbearance and benevolence" the business of the Christmas season, so to speak.

Those traits are "the basic pillars of Christianity," Standiford added, as well as "the whole notion of Christian charity that was at the center of Dickens' notion" of the "more fortunate taking responsibility for the welfare of the less fortunate" in society.

"It's part and parcel of western democratic norms today," Standiford said. "But that was not necessarily true in early Victorian England."

Beyond that, Standiford said "A Christmas Carol" also dawned many of the "trappings" associated with Christmas today — from exchanging gifts to sending holiday cards to decorating trees to singing carols and the like.

"What would Christmas be like today if not for Dickens and 'Christmas Carol'?" Standiford said. "I think it would have remained the relatively minor holiday it was before. I think it would barely be known. That's what I think the impact of that book is. If you trace everything that has happened since the publication of that book, and compare it to what Christmas was before, that's what the evidence says."

Jones, the host for the Dickens Christmas walking tour, insistently disputes that Dickens innovated the holiday.

"Jesus probably has a bigger claim to having invented Christmas than Dickens ever did," he quipped. "Did Dickens invent Christmas? No he didn't. Did he reinvent Christmas, as has been put forward as a compromise? No he didn't."

Rather, he explained, Dickens provided a "blueprint" for celebrating the holiday.

Or maybe Dickens simply provided an early example of a 'Christmas miracle'?

Rather, Jones claimed, Dickens "simply jumped on a bandwagon that started rolling" in the 1820s. And in America, of all places, and by Dickens' erstwhile literary pal, Irving.

Jones related how Irving moved to England in 1815 and subsequently wrote five stories between 1819 and 1821. Those essays dealt with a Christmas in a fictitious location in Yorkshire and told the story of a squire that wanted old Christmas traditions to be continued.

The essays became extremely popular, Jones told, as people of the time worried their holiday customs were being lost as the Industrial Revolution broke family and community bonds.

"Traditions were being lost and people started to panic about this in the 1820s," he said, adding that a movement then mobilized to collect traditions such as carols that were sung, recipes for dishes served and games that were played. Plus one other staple of the holiday — telling ghost stories — that Dickens exponentially rocketed in popularity with his tale of the three Christmas ghosts who help reinvent Ebenezer Scrooge.

"These were published each year as Christmas annuals, and many middle-class people got a Christmas annual telling them how they could celebrate Christmas," he said.

Dickens had been an admirer of Irving, and friend until "American Notes," and the English author used many of Irving's ideas, Jones said. All told, Irving's writings, the annuals and the works of other writers were "threads" that Dickens sowed into a holiday quilt.

"All these things, the customs, the traditions, Washington Irving, they were all sort of often threads," he said. "Dickens was the one who pulled all those threads together and in 'A Christmas Carol' gave us a blueprint for the spirit of Christmas."

And in doing so, perhaps, he originated a "Christmas miracle" of personal renewal and redemption.

"If you told someone that you could prove that the meanest, most miserly, most self-centered man in the world could overnight change his mind and become a benevolent and generous and other oriented person, most people would say that's ridiculous, that's impossible," said Standiford at FIU.

But the success of "A Christmas Carol," he said, proves Dickens succeeded in making that story plausible.

"Charles Dickens made that happen. He made it believable. Dickens made the impossible possible," Standiford said. "The proof is in how that novel, and its many adaptations, have lived on for almost 200 years."

Antonio Fins is a politics and business editor at The Palm Beach Post, part of the USA TODAY Florida Network. You can reach him at afins@pbpost.com. Help support our journalism. Subscribe today.

This article originally appeared on Palm Beach Post: Dickens' Christmas Carol reinvented the holiday. The proof is in London.