This Designer Hasn’t Wasted Fabric Since 2003—Here’s How She Recycled Hundreds of Scraps for a New Exhibition

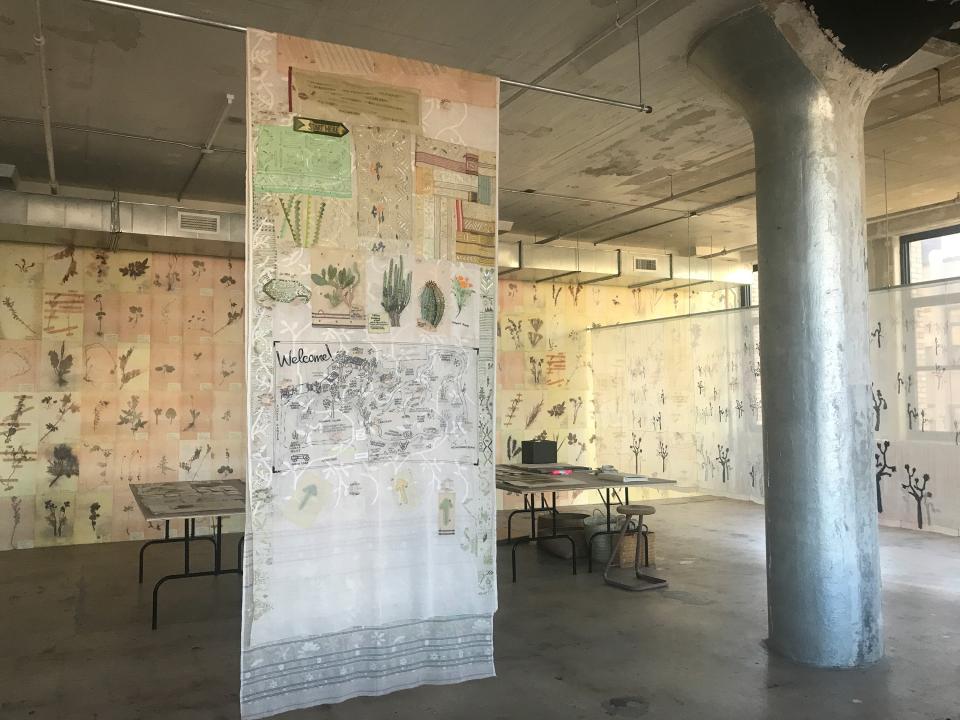

Dosa gallery

When Christina Kim started her label Dosa in the mid-’90s, words like upcycling, artisanal, and sustainable weren’t part of the fashion vernacular. Now, designers (and start-ups, beauty brands, etc.) are peppering those terms into press releases and Instagram posts with varying degrees of credibility. By contrast, Kim’s 20-plus years of hand-dying blouses, sourcing organic fabrics from India, and recycling leftover materials and garments into new, one-of-a-kind treasures puts her way ahead of her time. That said, her low-key success—she still has a shop on Thompson Street and sells her collections to specialty boutiques like Tiina the Store—mostly comes down to the fact that she never actually intended to be an eco-designer.

“I’ve always just been interested in materials,” she said. “When I started working in Oaxaca [in the ’90s], I realized what I love are the fabrics that are very labor-intensive and handmade. So I thought the best thing I could do as a designer is honor the time they’ve spent making the fabrics, and reuse them as much as possible. That’s how it all started.” She and her teams in New York and Los Angeles have been saving rolls of fabric, old samples, and scraps from the factory floor since 2003; they now have a sophisticated system in place for sorting the leftovers. The materials are then upcycled into pillows, textile panels, jewelry, and even entire garments, if there’s enough yardage. Kim pointed out the tiny fabric beads on her necklace and called them the “fourth generation” of recycling: First, leftover fabric is cut for clothing, then pillows, then eventually these amulets (even the stuffing inside is made of scraps!). “A group of women make these at home in India,” she added. “They’re on their own in terms of the design, and each one represents zero waste.”

Over the past few years, Kim has found a way to expand the concept even further—and on a much larger scale. In 2016, she piloted the exhibition Scraps: Textiles and Creative Reuse at the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum, which focused on the life cycle of jamdani—the plain-weave sari material Kim sources from West Bengal—and how scraps of it are saved, sorted, and repurposed at Dosa. After a successful run, the show traveled to George Washington University and was supposed to make its way to the Palm Springs Art Museum, but the Cooper Hewitt decided to add it to its permanent collection.

Kim was left with a blank slate for her Palm Springs show, and took it as an opportunity to rebrand her installation series as Flying Fish Project, now on view in Soho. “I wanted this to have its own identity, separate from Dosa, because this is more about my personal dreams,” she explained. “But I don’t see a difference between making clothing and making art. It all involves design, thinking, and making, and in some cases, clothing becomes art, because you can’t make more than one.”

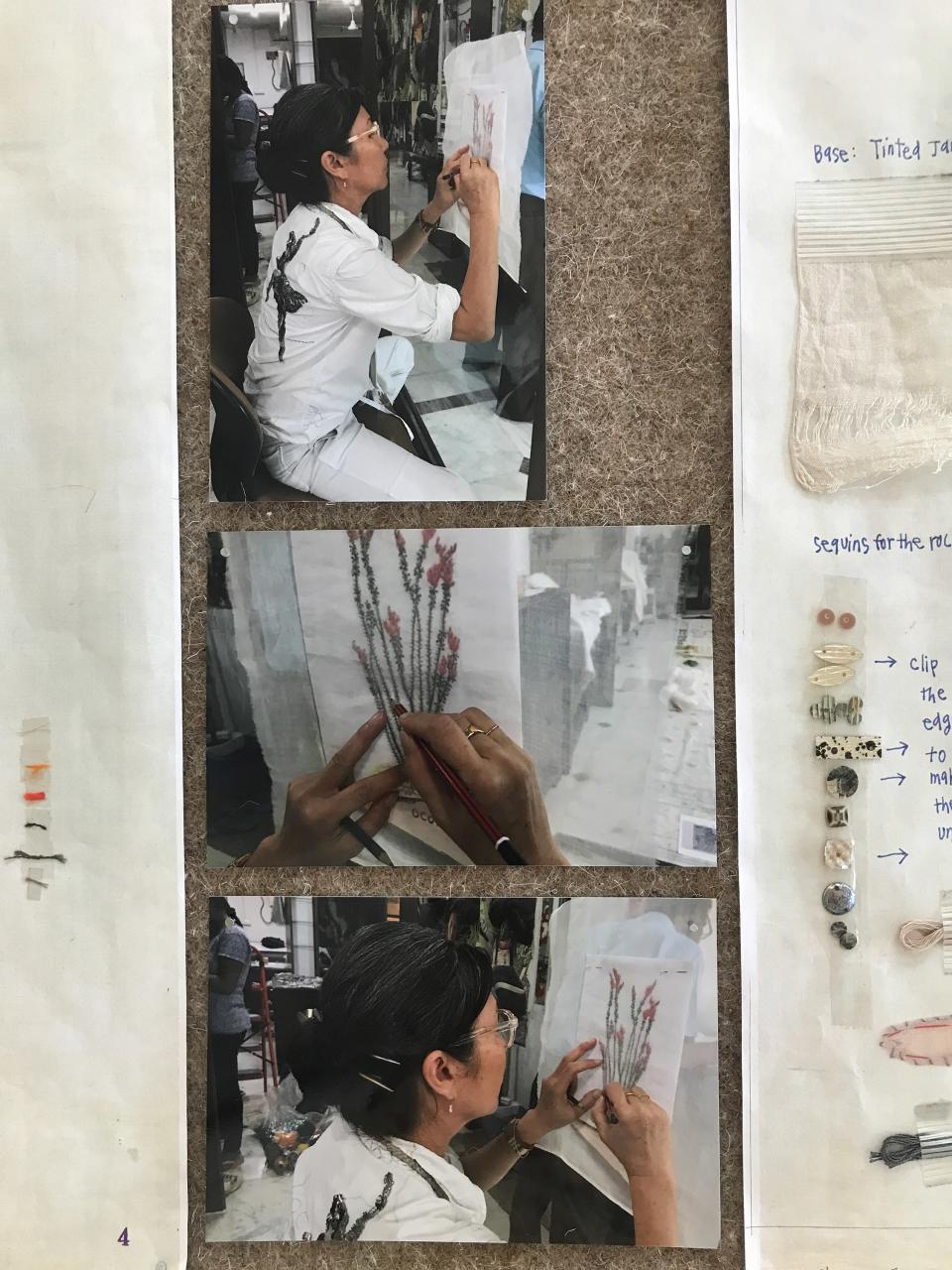

Where a hand-embroidered Dosa dress might be considered wearable art to Kim’s clientele, her newest Flying Fish production transposes that magic onto the walls of the home. Taking inspiration from a Palm Springs desert garden, Kim worked with her team of artisans and master embroiderers in Calcutta to create textile versions of specific plants—a California poppy, a prickly pear cactus, a palo verde plant, etc.—using scraps of fabric as if they were swatches of paint. To be fair, it’s impossible to capture the detail on a computer screen; seeing them up close and in person was a treat. Kim pointed out the subtle color gradations on a scrap of green jamdani, for instance, and in some cases, she and her team invented new types of embroideries to more closely mimic nature, like the X-shaped stitches forming needles on a cactus. Each panel is intricately detailed, yet charming in its simplicity. The “plants” are even accompanied by their own embroidered garden marker. (Also charming: On a wooden table in the studio, there was a pile of what this writer honestly believed to be real green vegetables—tomatoes, peppers—but upon closer inspection, each was actually made of fabric. They’d been carefully stitched and embellished in India using smaller scraps of fabric, just like Kim’s amulets.)

In the center of the space, you’ll discover the hero piece: a massive embroidered panel of white jamdani embroidered with a garden map, squares of sparkling hand-beaded fabrics, and more plants. It’s a large-scale, intensely worked symbol of what Kim hopes Flying Fish can become: a celebration of handwork, zero waste, and all things natural. (Visitors will notice that even the guest book is made of recycled paper—each page came from old agave leaves!—and the curtain of hanging beads at the entrance is actually hundreds of rolled up magazine pages.) You can see and shop the exhibit at 121 Varick Street now through August 31.

Originally Appeared on Vogue