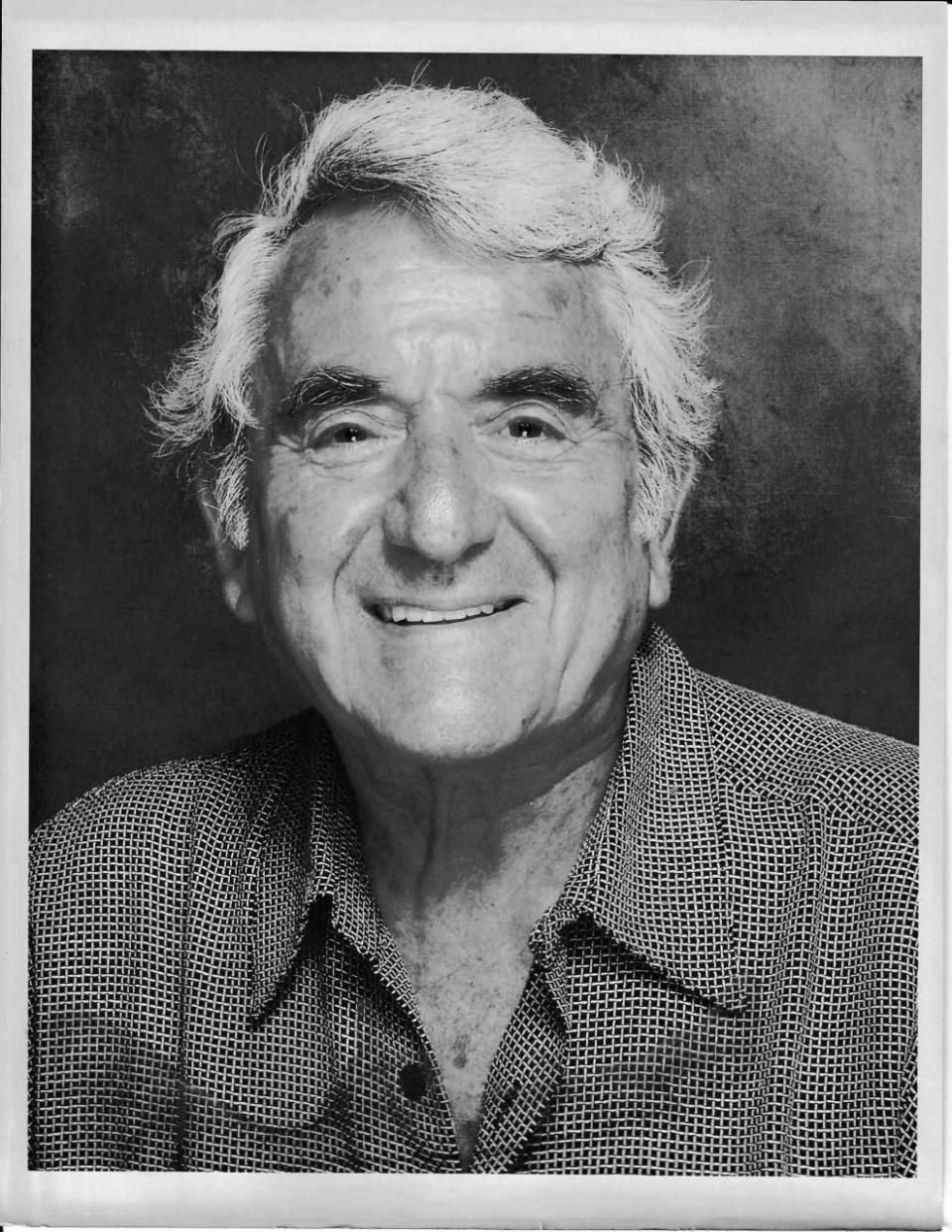

Designer and Bon Vivant Peter Barton Dies at 91

Footwear and menswear designer Peter Barton died Saturday at the age of 91.

He died peacefully in his sleep while at a rehabilitation facility in Oradell, N.J. The cause of death has not yet been determined, according to his wife Phylomena.

More from WWD

Plans for a memorial, which will include a military component due to his service in the U.S. Army, are still being decided on.

Born in Brooklyn and the son of a tailor, Barton was interested in and enjoyed art and design. He served in the U.S. Army during the Korean War and afterward started his fashion career as a shoe designer. With a knack for designing and making shoes, as well as styling, Barton later ventured into menswear — shirts, pants, outerwear, sweaters and scarves — and multiple other categories including household items and childrenswear. He seated his own operation focusing on footwear in 1954.

Absorbing the world beyond the realm of fashion, Barton was often out-and-about, seeing what’s what and immersing himself in a full-bodied life. His creativity and sense of style sprang from that 360-degree outlook. Starting out independently with his own office and showroom, Barton went on to sell his designs to many department stores. In the late ’70s, Peter Barton’s Closet opened at the Fifth Avenue specialty store Henri Bendel for a 10-year run. He served on the executive team at the retailer. Barton and Nancy Knox later cofounded Renegades Shoes, which was acquired by Genesco Inc., one of the early conglomerates in the fashion business.

Reflective of his multidimensional life, Barton bought a farm in Umbria, Italy, in the late ’70s. Frequently flying to Milan, Florence and other European destinations for work-related business, the designer was able to spend a good amount of time on the farm where he grew olives to use for his signature olive oil. Barton held onto the property for about a decade.

Kind, generous and charismatic, Barton was always caring about humans, life in general and the world at large, according to his widow. Although the designer officially retired from the fashion industry 10 years ago, he continued to work on beautiful scarves with the Dunlop Weavers, a small family-owned and -operated textile mill in Orland, Maine. “Even though he retired, he was retired but not,” his wife said, adding that he still attended shows in Chicago, Las Vegas and other locations.

In touch with Barton every day or two, designer Alexander Julian considered him to be a mentor. “This guy understood good taste, quality and elegance more than anybody,” Julian said.

Positivity remained his calling card, even in recent weeks, according to Julian. “He told me he was only going to concentrate on the good things and not even think about the bad ones, because there were so many bad ones going on. He was positive up until the end,” the designer said.

As a buyer for Julian’s, his father’s Chapel Hill, N.C., store, Julian first met Barton through his collection. Julian continued to buy from Barton after he opened his own store, Alexander’s Ambition, in the ’60s across the street from his father’s outpost. “I grew up in the business, but Peter taught me about being a three-dimensional person. There are a lot of people in every industry that get consumed by what they’re doing and don’t live their lives to the fullest. Peter did and was an example to me of that,” Julian said. “He didn’t really want to talk to me about what sold. He wanted to talk about a film, a book, an art exhibit, a new restaurant, a wine. He had a fantastic farm for many years in Umbria. My wife is a gourmet cook and she used to buy his olive oil before she ever met him.”

Courtesy of Peter Baron

The Italian olive oil was sold at Henri Bendel and by specialty store retailer Jerry Magnin. Noting how Barton also made wine on the farm, Julian described how he and his daughter visited Barton in Tuscany years ago. “I can still picture Peter driving on the Autostraddle at 100 mph with us in the backseat and him turning around to describe something using both hands on a curve,” Julian said, adding that the thrice-married Barton lost the farm in his second divorce settlement.

Barton was the sole member of Julian’s board of directors “because he had gone through everything twice. He always knew what to do in any situation,” the designer said. “He was part of that brilliant generation, who lived in Brooklyn in Brooklyn’s heyday. He was about 16, when he joined a big band and traveled the United States as a saxophone player.”

Jerry Magnin, who ran his own signature Rodeo Drive store in Beverly Hills from 1970 to 1987, carried Barton’s label there. As the first retailer in the U.S. to pick up Giorgio Armani in the early ’70s, Magnin cited Bill Kaiserman’s collection as another standout and included Barton in that group that came to the forefront in the ’70s. The retailer described the mid- to late-’80s as really the heyday for independent menswear stores before larger stores such as Barneys New York, Saks Fifth Avenue and Neiman Marcus started offering menswear lines that the independent stores had first developed. “They would go in with these monstrous orders, take them over and sort of push us out of the way,” Magnin said. “I can’t tell you how many discoveries we made.”

Never without a sparkle in his blue eyes and a smile on his face, the perennially tan Barton was always visibly happy to see you when you walked into the showroom, Magnin said. Dressed perfectly, the curly haired enthusiastic designer was full of great ideas, and original ones, too, according to Magnin (whose family had established the I. Magnin) retail company. Not one for suits or sport coats, the designer often sported his own shirts sometimes with one of his scarves. “He really had a style all his own. His style would be the South of France in the ’20s or the Florida Keys, but before it was what it is now,” Magnin said. “It was stylish elegance but not overpriced.”

Although Barton specialized in menswear, many of his accessories could have been men’s or women’s, according to Magnin, who described his style as “edgy, traditional.”

“If Ralph Lauren was traditional, he was a little edgier. For example, if Ralph had a linen shirt, it would be more conventional. Peter’s might be a little wider shirt that might be a style from Mexico or the Philippines, but still in the traditional vein. Peter had the most gorgeous scarves,” Magnin said.

Barton kept large jars stocked with European licorice, which Barton recommended like a connoisseur based on an individual’s personal taste. Magnin explained, “I happen to love real licorice, which is extremely hard to get. The stuff you get here is just sugar with coloring and flavored. I couldn’t wait to get to the showroom to get my hands on the licorice [laughs.] I think I got more out of the licorice than he got out of my order book.”

”Open, welcoming and always your friend,” Barton was always anxious to show you something and to chat, Magnin said. Visitors were never greeted with a salesman pitch and a pull of assorted styles from a nearby rack. “He really romanticized his products. If I had to characterize him, I would call him Peter Barton, romantic couturier — with good licorice.”

In addition to his wife, Barton is survived by a daughter, Sophia Bianchi, who was named after Barton’s mother. With three sons, Bianchi is expecting a fourth child, a girl in August, the birthday month that her father was born in. “Peter got to know that she was going to have a baby so he got to live all that with her,” Barton’s wife said.

Bianchi later added, “He kept saying he was trying to hold on until August.”

Best of WWD

Sign up for WWD's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.