This New Design Book Offers a Cure for the Modern Farmhouse Epidemic

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

In 2003, Heide Hendricks and Rafe Churchill, principals of the architecture and design firm Hendricks Churchill who are also married to one another, first set eyes on what would become Ellsworth, their family home in Litchfield County, Connecticut.

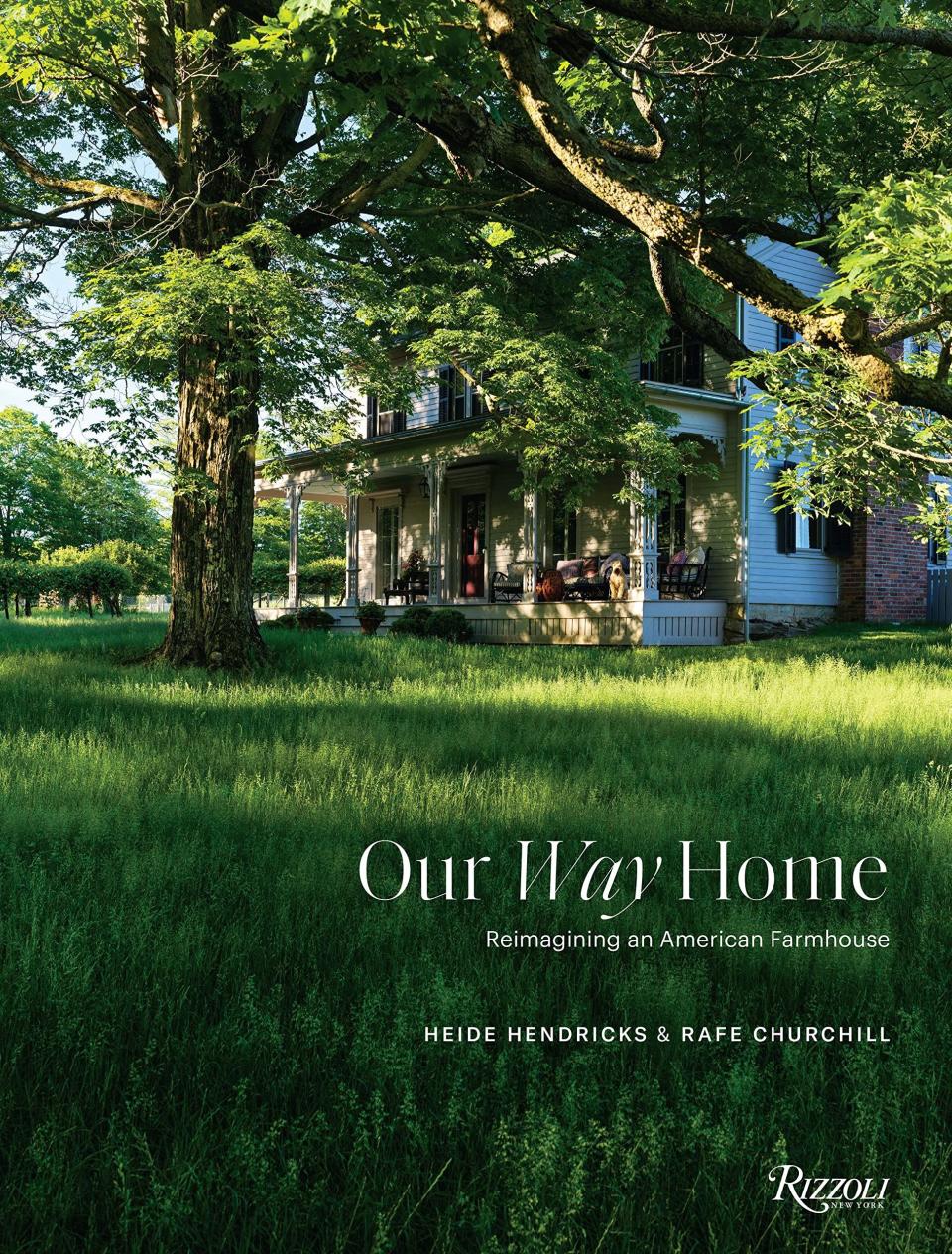

It would take another 15 years of driving past the 1871 farmhouse and “dreaming of the possibilities but never imagining it might one day be theirs,” as described in the introduction to their new book Our Way Home: Reimagining An American Farmhouse, out September 5, for the couple to buy it.

Our Way Home: Reimagining an American Farmhouse

amazon.com

$65.00

During that time, Hendricks and Churchill had also added to their family, renovated three other homes, and built a successful design business upon the foundation of their authentic, warm, and subtly playful style and collaborative, unpretentious approach. That period of growth perfectly primed them to create their dream home at Ellsworth, which they have documented in beautiful and remarkably personal detail in their new book.

Today, the house presents itself as a sanctuary of self-expression, yielding at appropriate moments to history and setting. Many of the rooms, furnished with an intentionally timeless mix of antiques and contemporary pieces, are cloaked in wallpapers that echo the environment and framed by painted millwork that accentuates rather than obscures existing eccentricities. There’s an undercurrent of excitement about the potential for discovery to the spaces, the style of which is certainly not for everyone.

Which may be precisely the point.

Hendricks’s and Churchill’s story of Ellsworth is compelling not just for its beauty, but also for its deeply personal reflection on making a house a family home. It’s a story over twenty years in the making and highly specific to their needs, desires and dreams. And while a 19th-century house in rural Connecticut with quirky trim may not appeal to all, the yearning for crafting our own havens, our own sanctuaries of self-expression, surely does—especially if we allow ourselves time and space to reflect on what we really want.

In the algorithm-driven world in which we live, self-discovery of any kind has become harder and harder. Our own voices are perilously drowned out as we are inundated by streams of sameness, particularly on social media but increasingly on other platforms as well.

Specific to residential design, the so-called “modern farmhouse” style is perhaps the most egregious offender, with its white siding, black windows and sea of subway tile and Shaker cabinetry popping up everywhere, from Pinterest to the Presidio (could there be anywhere less agrarian than San Francisco?).

As real estate reporter Ronda Kaysen wrote in her thoughtful article in The New York Times, “The modern farmhouse is the millennial answer to the baby boomer McMansion….dominating renovations, new construction and subdivisions in communities with no connection to farming.”

Algorithms and the ensuing influencer-dominated echo chambers in which we now exist have not only given rise to design ubiquity but also stoked the instant gratification fire of American consumerism. When we’re honest with ourselves, all of us can acknowledge having experienced the following internal dialogue: “So-and-so is everywhere, and I simply must have it—NOW.”

Of course, nothing about creating a home is instant—or needs to look the same for me as it does for my neighbors. Homes are repositories of memories and moments that comfort us with so much more than shelter, and they take decades, sometimes lifetimes, to cultivate. Further, what makes American neighborhoods, towns, cities, and even rural communities rich with culture and interest is the idiosyncrasies among us—and our opportunity to share them with each other.

Perhaps it’s fitting, then, to look to a pair of artists with “a shared appreciation for Yankee ingenuity, the value of artisan craft, and for freedom from convention,” as described in the introduction to Our Way Home, for a remedy to the ills of design homogeneity sweeping across America. Here, five ideas from the story of Hendricks's and Churchill’s home for curing the modern farmhouse epidemic.

Start a reno by making a list of what you don’t want to change.

Call it the “first, do no harm” approach to renovation. Henricks and Churchill mapped out their plans for Ellsworth by considering what they didn’t want to amend about the 19th-century house, which needed quite a bit of work to bring it to current living standards. “We definitely considered how our family would live in this house, but first we outlined for ourselves what not to do,” Churchill says.

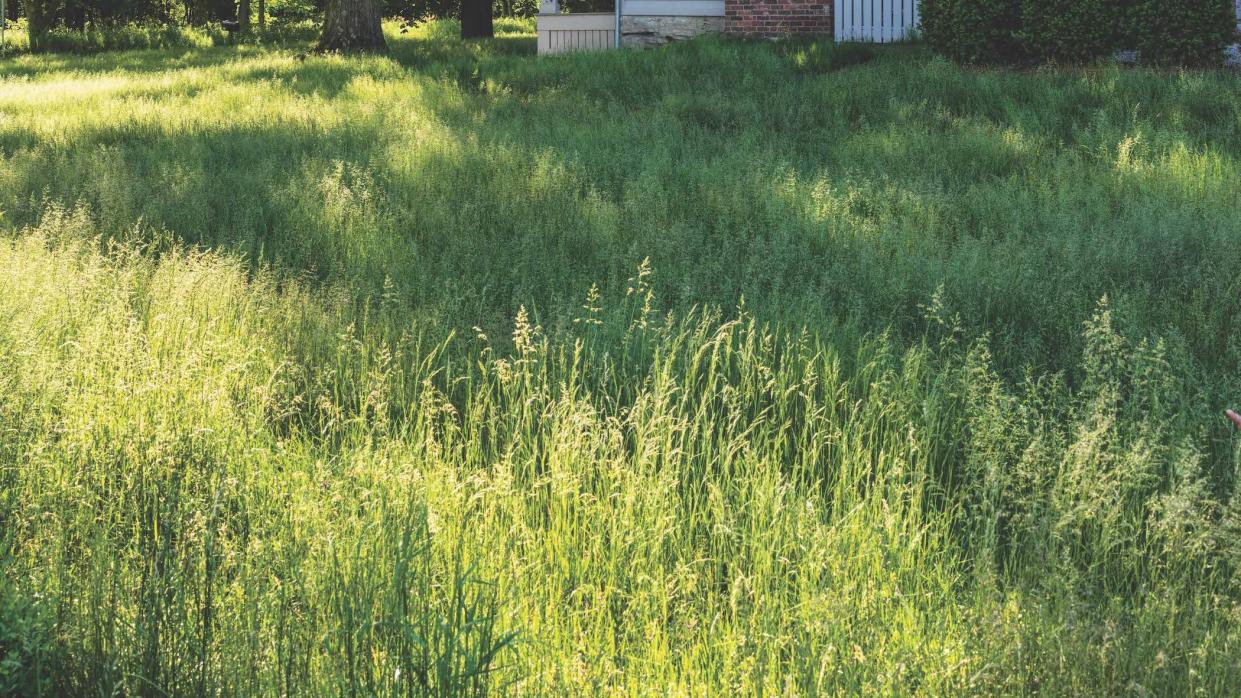

For example, they decided upfront they would not enlarge the 2,900-square-foot house, and even lopped off a small shed from the side of the house that had been used as an outhouse. “The history is important to us, but most significant is how the house and immediate landscape influence each other, resulting in a beautifully respectful partnership,” he adds.

Inside, the design duo navigated a delicate balance of updating the house for 21st century family life while “making occasional sacrifices in honor of the bones of the house,” says Churchill. “Our most successful projects are those that keep the egos in check while learning how to live with an old house.”

Keep the character, skip the extra bathroom.

Among the bones of the house that Hendricks and Churchill decided to honor is a narrow, steep back staircase that drops from the second story bedrooms into the kitchen—the kind of thing that is “usually removed in favor of adding more storage space or an additional bathroom,” the book states. “We kept this quirky detail because it really adds character to the kitchen. It’s what makes an old house an old house,” says Hendricks.

Leaving the stairs in place meant they had to forgo adding a third full bath, which “would have would have been nice, but keeping up with two and a half is really enough,” Churchill says. “We figured that if you’re staying with us, you must be a good friend and will accept that sharing a bathroom with our kids is just part of the experience.”

The couple also left in place a few imperfect millwork details that had had been added over the years, such as scrollwork applied on the front hall’s exposed stair stringer. “You can’t help but think about the person who made it and what was going through their head at the time,” says Hendricks. “These kinds of details let the imagination run wild — whether the stories we come up with about them are true or not.”

Choose room colors that make you feel good.

Another element Hendricks and Churchill did not scrap was the house’s existing floor plan, preserving its center hall orientation with rooms assigned distinct functions rather than bringing down walls to create an open plan. Despite many discovering with the perils of open plan living during the pandemic, the layout persists in modern farmhouses, which often feature “great rooms” designed for cooking, eating, living, working, and even exercise and are typically colorless. Whatever convenience or togetherness is gained from such a design comes at a cost: Lost is the opportunity to experience change in light and variety in color and view, all of which affects mood.

When designing the interiors at Ellsworth, Hendricks spent a lot of time thinking through when rooms would be used, during what seasons, and how light changed each to inform her color selections long before she made any decisions about furniture. For example, because the living room has the only fireplace in the house, Hendricks knew her family would use it most often during winter and thus chose a darker, moodier palette of greens, reds, and aubergine for coziness, and because they would look “even better by firelight.”

Hendricks also chose a darker scheme for the mudroom—in this case a purple-gray. “Using dark colors in an entry is a great strategy to adjust your eye from the outside. When you enter the mudroom on a bright day, your eyes immediately begin adjusting to the interior space. It sets a tone, and the next room you walk into automatically feels bigger and brighter,” she says. “Conversely, the [nearby] laundry room is a bright yellow. It’s a happy yellow for a dreary task.”

Allow your home to evolve alongside with you.

Soulful homes, like their owners, are works in progress—not altars of instant gratification. Some of the most beautiful moments at Ellsworth are the result of tinkering and tweaking over time. Take the color scheme in the kitchen and its adjacent pantry—a pastiche of light, medium, and indigo blues—which is the result of a disagreement between Hendricks and Churchill that took years to resolve.

Hendricks chose Farrow & Ball’s De Nimes blue for the cabinets and beadboard, even knowing that blue is said to be an appetite suppressant, and a lighter Farrow & Ball shade, Borrowed Light, for the pantry. A few years in, Hendricks felt the kitchen to be too utilitarian in feel and Churchill complained the pantry color felt cold. To soften the kitchen, Henricks added a floral block print wallpaper (Soane’s Dianthus Chintz) on the small wall spaces not covered in beadboard.

The pantry solution took a little more negotiation, creativity, and time. “Rafe wanted me to consider changing the color, but I still really liked it. So we came up with the idea to take the darker blue from the kitchen and ‘spill’ it in the pantry as if it came in from a flood and left behind a waterline. That was Rafe’s analogy when he was trying to sell me on the idea. And he did. It was a good collaborative moment.” Now, the room stands as a testament to the art of compromise and the beauty that comes from waiting for the best idea to bloom.

Fill your home with things that bring you joy.

Designed with color, pattern, furniture, and artwork meaningful to Hendricks and Churchill, Ellsworth is an original reflection of its owners. It’s clear that while they were thoughtful and studious in their approach, the couple was never consumed by trends, resale, or even “correctness.” Instead, they made design decisions that reflect what they love and value. The rooms in turn invite guests and friends to learn their story and get to know them even better.

It was deeply important to the couple, for example, to pay homage to the surrounding landscape inside, so Hendricks chose wallpapers that relate to the property. Mark Hearld’s Harvest Hare wallpaper in the dining room echoes the hares in the surrounding fields, while Marthe Armitage’s Chestnut wallpaper in the powder room is a nod to a Japanese chestnut tree in the front yard. A pine wallpaper by Fayce Textiles in the living room honors some white pines that had to come down to protect the house.

Hendricks furnished the house with a lively mix of antiques and vintage pieces, old hand-knotted rugs, and contemporary elements like lighting fixtures and art—which together engage in a friendly banter-like dialogue, never too serious.

“Whether it’s a bespoke piece crafted by some artisanal studio or a mass-produced object, it has to convey a message, preferably a humorous one, or provoke an emotion,” says Hendricks about selecting pieces for her home. “I like to imagine when I’m designing and furnishing these spaces that I’m making my mark in time — even after we’re gone, those pieces will tell the story of our time in the home.”

You Might Also Like