Why We Need to Decolonize Design—And How to Do it

When Malene Barnett went to design school, she hoped to explore design history and influences from all over the world. But it quickly became clear that the only thing on the curriculum was Eurocentric design.

“My work was all about the Black experience and I wasn’t going to settle for what was offered,” Barnett says. So she decided to focus on symbols, textiles, techniques, and artisans from Africa, the continent where all life began.

South African Ndebele colorblocking inspired her stationery project. She won a carpet design award for her rug that depicted an African folk tale. For her dinnerware pattern, her “client” was Ghana’s Ashanti royal family. Some professors got it, some didn’t, but she persisted. “I was very clear about my voice and vision and I was confident,” Barnett says. She graduated with honors, and won the department medal.

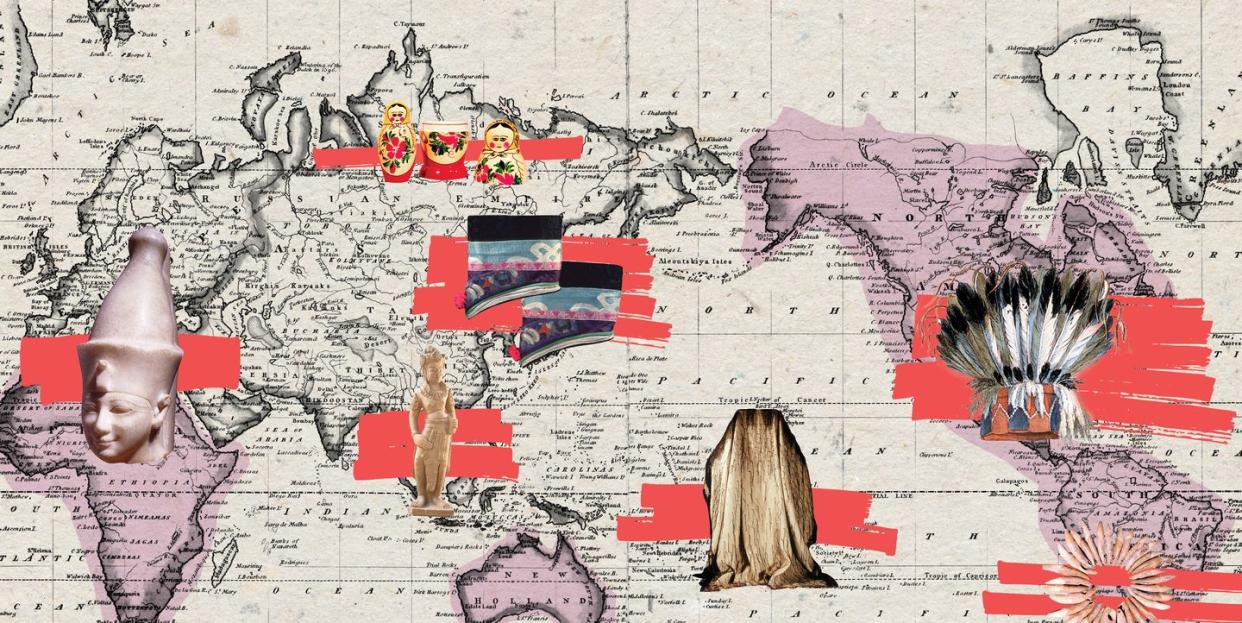

Now, as an acclaimed ceramist, painter and textile artist, Barnett wants to help other designers "decolonize" their design thinking to embrace people, design processes, materials, and methodology from around the world. Here's what she suggests.

Get rid of labels

Words are just words, but they shape how we think and what we value. “Why is it that the only time you think about the work by Black and Brown people they’re put in Bohenmian-tribal-ethnic?” Barnett asks. Ditto for "primitive," a demeaning term seldom applied to white people’s work. “These words on their own are not bad words, but white people have created this division between what is high and low and what you should aspire to,” she says. "They’ve assumed the authority to decide what’s in or out when talking about work by Black and Brown people."

Abolish design categories

We often categorize decor as having modern or traditional aesthetics. The Eameses and Eero Saarinen are icons of midcentury modernism. But did you know you can find modernist design in Mexico–just look at the National Museum of Anthropology by architect Pedro Ramírez Vázquez. Or consider British-Ghanaian architect David Adjaye, best known for the National Museum of African American History and Culture. And does “traditional” conjure Chesterfield sofas, wingback chairs and other 18th and 19th century European trappings? Lacy Bamileke tables, carved from a single tree trunk, have been traditional choices for Cameroonian rulers for centuries—what could be more "classic" than that? Freeing yourself from conventional categories allows more creativity.

Broaden your references

It’s natural to define design in terms of artists we know, such as Picasso, Monet, or Van Gogh. Barnett urges designers to educate themselves on artists outside of Europe, too. Go deeper with Henry Ossawa Tanner, the first acclaimed Black American painter who specialized in religious art and scenes of daily life; Romare Bearden, whose work spanned abstract expressionism and Cubism; Elizabeth Catlett, a sculptor and graphic artist from the Harlem Renaissance era.

Travel somewhere new

Taking trips to see where furniture or fabric is created is a vital part of learning about design and creating interiors with meaning. But when you grab your passport, where do you go? It’s fun to jet to Paris or Tuscany, but many designers aren’t as interested in heading to Dakar, Kingston, Jamaica, or Guyana. “That is a loss, particularly because they’re not understanding the people, the culture, and the lifestyle,” Barnett says. And while it's fine to appreciate what you see abroad, don’t come back and “interpret” those designs into your own work (instead, endeavor to directly support the people creating that work).

Learn how things are made

Many people believe Italian-made textiles are superior to those from India or Ghana, but that changes when you dig into how things are made. “When it comes to interiors, our culture is used as an accent, but designers don't know anything about the Bambara,” she says. True African textiles, from mudcloth to kente to Kuba cloth, are created through painstaking weaving processes. For mudcloth, Bambara men of Mali weave strips of fabric, stitch the strips together, and dye them in fermented mud. It’s usually black and white, but they also make a gorgeous indigo version. “You cannot separate the culture from the people," says Barnett. "We need to get back to understanding the culture, the people and the originators. That is part of decolonizing this design process. Once you do these five things, you’ll have a fresh canvas and your creative process will constantly evolve."

Follow House Beautiful on Instagram.

Maria C. Hunt is a journalist based in Oakland, where she writes about design, food, wine, and wellness. Follow her on instagram @thebubblygirl.

You Might Also Like