Our December Sip and Read Club Pick Is "AphroChic: Celebrating the Legacy of the Black Family Home"

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

Welcome to the VERANDA Sip & Read Book Club! Each month, we dive into a new book and offer exclusive conversations with the author, along with a perfectly matched cocktail. This month's pick is AphroChic: Celebrating the Legacy of the Black Family Home. In their second book, Bryan Mason and Jeanine Hays celebrate the joy that is the Black family home by showcasing striking interiors from artists and creatives that defy stereotypes. Get caught up on our past book club selections here.

Bryan Mason and Jeanine Hays, the powerhouse duo behind interiors and lifestyle brand AphroChic, knew that their second book couldn't be an average design book—it needed to not only celebrate beautiful interiors, but also paint the picture of Black ownership in America. AphroChic: Celebrating the Legacy of the Black Family Home takes readers into the homes of sixteen luminaries whose spaces showcase the rich diversity of Black design and culture. In between each tour lies a history lesson on the obstacles Black families and homeowners have faced over the centuries. Here, Mason and Hays talk about what inspired them to write AphroChic and the lessons they hope readers take away.

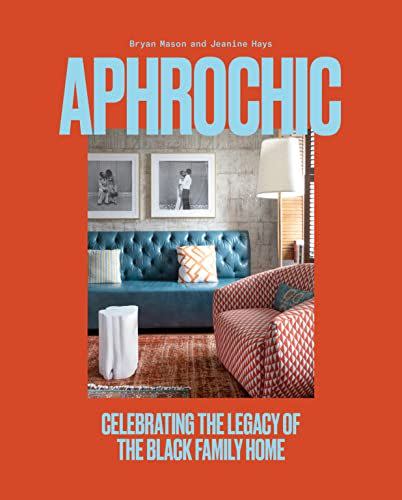

AphroChic: Celebrating the Legacy of the Black Family Home

amazon.com

$31.50

amazon.comIn your own words, what was the inspiration behind this second book, and what was the writing process like?

Bryan Mason: There were a few different things that came together to inspire this book. In 2020 when we signed to write AphroChic, we were at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic and the outset of the Black Lives Matter marches that defined much of the year. Around that time, we were reading about the experiences of enslaved African Americans at the moment of Emancipation. Turned out into the streets by former owners they were left to die en masse. Before that, many who made it to Union lines were either returned to the South, put to work by the Union army, or imprisoned.

We were also reading about the (then) current rate of homeownership for African Americans, which had dropped to its lowest level since the signing of the Fair Housing Act in 1968. That drop was predicated largely on the Great Recession of the early 2000s, itself caused by predatory subprime lending practices that disproportionately targeted Black homeowners and other people of color. We also saw the disproportionate impact that COVID was having on the Black community economically as well as medically as lost jobs and wages were translating into lost homes.

We saw, not for the first time, the ways in which American society shapes itself to ensure that people of color take the hardest and most enduring hit from any crisis or disaster, whether natural, medical, or financial. And we saw how the absence of the Black family home from nearly all public conversations or mainstream representations played a role in preserving that arrangement.

Jeanine Hays: At the same time, a few months earlier in 2019, we had begun AphroChic Magazine, our quarterly lifestyle magazine focused on the design, fashion, food, music, and culture of the African Diaspora. One of our recurring features, now titled "Black Family Home," focused on a home that has been in Bryan's family for several generations, having been purchased originally by his great-grandmother and great-uncle in the 1950s. We wanted to show, first, that these generational homes do exist in Black families and to represent the warmth, love, and joy of those spaces.

So as we [approached] this book, we welcomed the challenge of writing something that not only represented and conveyed the Black experience of home but also, showed that experience fully—its joys and its struggles—and in its full context, reconnecting it with the history from which it is so frequently excised with the hope of shedding light on the current moment.

How did you go about finding these incredible homes that flawlessly tell the story of Black homeownership in America? Were there certain criteria you were following?

BM: The homes that we curated for the book are all very different. That was important to us. In those moments where the Black family home does appear in popular culture or mainstream media, it tends to fall into one of the three tropes we outlined in the book. So one of the first things we needed to do was represent the diversity of Black homes and by extension that of Black experiences and Black life. But we still wouldn't call that a criteria because we didn't compare one home to another to see how closely they fit or set out to pick homes with widely divergent styles. We didn't have to. Instead, we looked for homes that clearly conveyed the person who lived in them. Because the people were different, the homes were too. Their connection to the history of the African American "journey to home" was equally organic. These homes are part of that history, so it was less a matter of finding homes with a particular connection and more of highlighting the connection that each home had.

JH: Many of them were people we already knew, and in the case of Danielle Brooks and Dennis Gelin, theirs was a home that we had designed. Some—like those of Bridgid Coulter, Ariene Bethea, and Colette Shelton—belonged to interior designers, but for the most part, they are the homes of people from all types of professional and personal backgrounds who have amazing style.

Rather than categorizing Black design in terms of eras or styles, you lay out five tenets: safety, control, representation, celebration, and memory. How do those tenets manifest in the homes featured in the book?

BM: There are a number of ways in which these tenets appear from one home to another. For example, memory, which is present in Alexander Smalls' home in gallery walls of photos is also present in Paul Suepat's home through the rough texture of the surrealist sculptures he creates and which remind him of the many textures he experienced and worlds he imagined in the woods behind his grandmother's home in Jamaica. In Joe and Camille Simmons' home, it's a toy plane that they bought for their son Milo, to remind him of the long history of careers in aerospace that both sides of his family have. And in Ariene Bethea's home, it's furniture that she grew up with and inherited from her mother and grandmother. Reading the stories that fill this book shows that for each tenet there are many tangible and intangible manifestations present in each home.

Throughout the book, every home embodies this sense of soul that you speak about in the introduction. How does one, when they start decorating their new home, instill this sense of soul or celebration? Is it less about the pieces and colors in the home and more about the intention that's put behind the decoration?

JH: One of the things that is so special about the homes in this book, is that each has its own flavor, its own style. This is an important component of African American culture, and it translates beautifully in these homes. There are no design rules here, but instead, the homeowners are utilizing the home as a canvas to express who they are, to remember their family history, and to build towards a brighter future. That's where the soul comes from. These homes are direct reflections of the inhabitants within.

What is one lesson that you hope people take away after reading this book?

JH: That the Black family home is a missing character in far too many of our mainstream media offerings. In most of our shelter magazines and books, design is only presented through a Eurocentric lens. Yet design is, by nature, diverse. It belongs to every culture. The work that goes into restricting design to a narrow and "normalized" cultural viewpoint lessens us. When we only present one cultural lens, we all lose. We hope that this book opens people's eyes to African American culture and creates a desire for more books that tell fuller stories of America, design, and history as a whole.

BM: The absence of the Black family home from pop culture representations and historical conversations is more than oversight or happenstance, and it's not a recent phenomenon. It is an important element in a construction of reality that euphemizes the oppression of one group of people as the "privilege" of another, that obliviates a history of aid programs and government assistance in favor of mythologized "bootstrapping" and ignores the continued impact of systemic racism, both past, and present, on the lives, health, and opportunities of a significant portion of the American population. There are no sidelines in oppression. Active participation and passive condonement strengthen it equally. We all have a responsibility to challenge this construction as we are all affected by it—especially those of us from whom it requires nothing but silence.

That the story of the Black family home is not just Black history or American history—it is history. Too often we're encouraged to view the present moment in isolation as if it is not only the most recent outcome of a number of ongoing historical and social processes. This makes it easy to think that "the way it is" is the way it always has been and makes it hard to challenge present circumstances.

You Might Also Like