My Decade of Temporary Homes

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

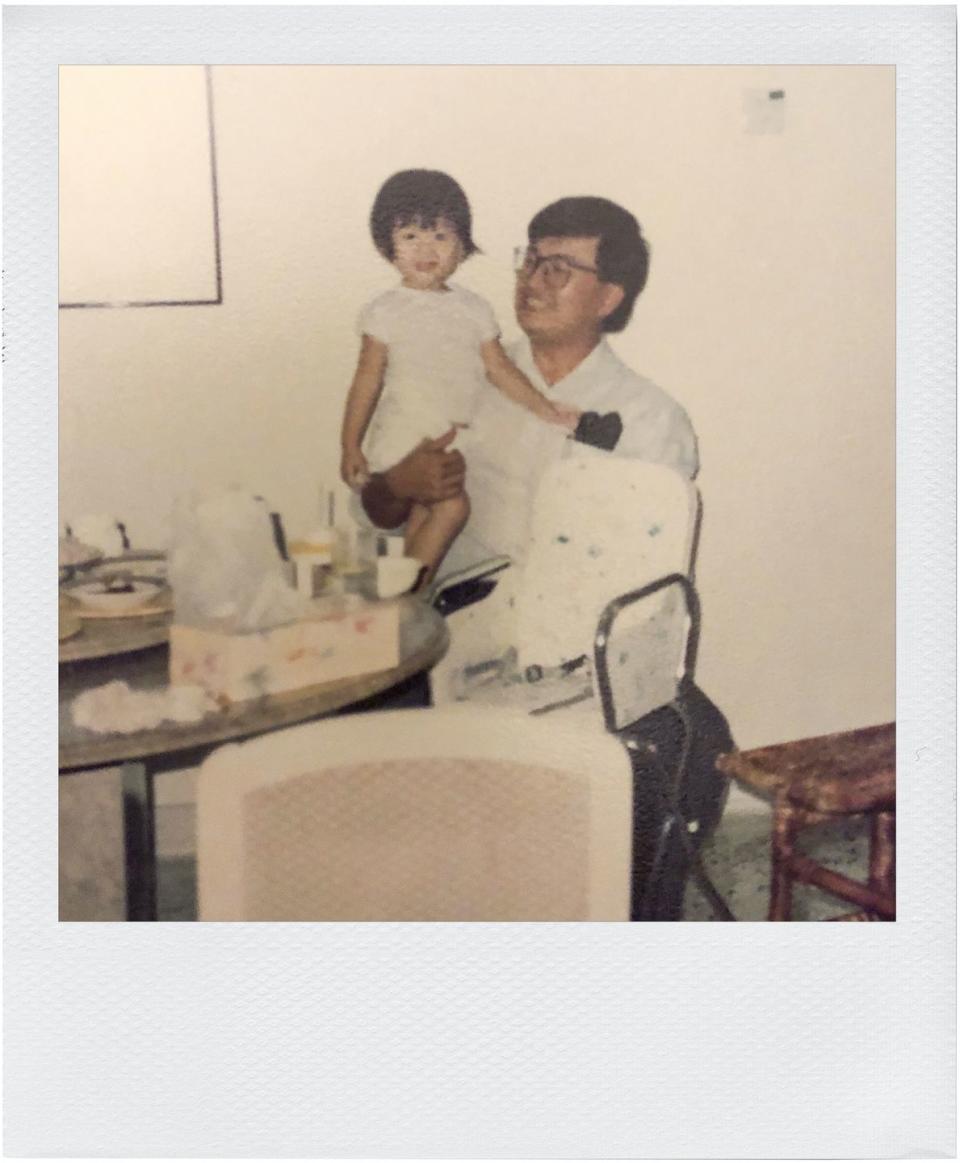

The first home I remember is the one we lost. It is startling and vivid in my memory, the way that childhood sensations are. The rounded corners on each step of the wooden staircase, on which I bruised my shins. The pink enamel bathtub in my parents’ bathroom, where my father once submerged me in scathing purple water to calm a massive outbreak of hives after being bitten by an ant. The rough terracotta tiles of the roof I’d climbed out onto from my bedroom window one evening, to the alarm of the family across the street who spotted me sitting out there calmly in the twilight.

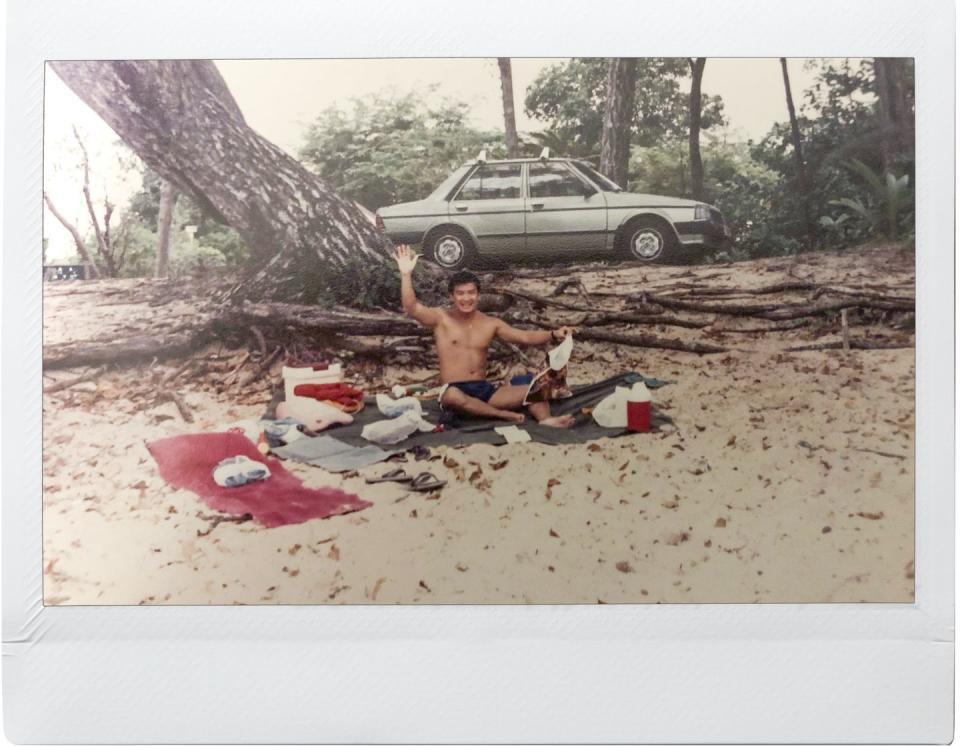

We lost this home when I was nine. In hindsight, the signs were clear. For years, our family holidays had been to destinations that featured casinos: cruise ships, Genting Highlands, Las Vegas. In my earliest memories I see my father standing before the dark television screen glowing with red and green numbers, stock market indices ticking up and down, up and down, as promising as Christmas itself. Another time, he gave me Roald Dahl’s The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar to read, a story about a gambler who, through intense meditation, masters the ability to see through playing cards and predict the future, then uses his powers to make a massive fortune in casinos. My father believed he was a kind of Henry Sugar, gifted with the power of a sixth sense. Before school exams, he would run through elaborate mantras and visualization exercises with me. Our minds, he explained, could bend reality, if we only tried hard enough.

Needless to say, I believed him, adored him, and would have done anything he said.

My father was a charming man. Large of belly and thick of neck, with an appetite for lard-heavy meepok, fried Spam, and braised pork belly. He could and did talk to absolutely anyone. He was my cousins’ favorite uncle and my classmates’ favorite Dad. In status-conscious and grades-obsessed Singapore, his humor and irreverence was a breath of fresh air. He made you feel like the strict rules that bound our society were of no consequence at all. He used to make fun of one particularly competitive aunt (all three of her children would not only become doctors, but also marry doctors) by saying she introduced people by their O-Level results, akin to introducing someone by their SAT score. This was easy enough for my father to mock; to him, academic achievement came easily enough. By dint of last-minute cramming, he’d done well enough to win a highly selective scholarship to study law, lifting him out of a childhood strained with financial difficulties. Amongst his peers in law school were men who would go on to become important judges and the legal counsel of powerful politicians. I see, in hindsight, how mastering the ability to see through cards did not seem like an impossible thing to him. He had made seemingly impossible things happen before.

When my father was a young man, my mother once told me, he would buy new TVs from electronic stores on credit, then sell them to used electronic stores, and pocket the cash to either gamble or pay off more pressing debts.

“How could he think that could possibly work out?” I asked bitterly as a young adult, a straight-A student assiduously trying to overachieve my way out of my past. My mother would only shrug in response and shake her head.

Miraculously, it did work out—for decades. Somehow my father was charming and resourceful enough to juggle his growing debts, all while rising through the ranks at his law firm and eventually making it to partner. From the outside, our family was a story of successful social mobility, a testament to Singapore’s rapidly rising standards of living. My mother had grown up in a wooden shophouse with a tarp for a ceiling, where rain would bring cockroaches floating in the water that leaked in, while my father was raised in cramped flats in which his mother routinely ran out of money at the end of each month. And here they were, in the nineties, in an entire house of their own, two children, a car.

Until it stopped working. My father vanished one afternoon, ostensibly traveling for business, but in reality, he had absconded. Years later, I would come to know that the debts he’d left totaled millions; that he had lost a great deal not only gambling in casinos but in stock markets rocked by the Asian Financial Crisis; that he had used his position as a senior lawyer to siphon off money from client accounts to pay his debts; that the police were involved and criminal charges were brought against him. Years later, I would find out he had borrowed money from literally everyone, from colleagues to classmates to distant relatives. From pawning jewelry to remortgaging the house, it was the television set ruse all over again. Years later, when I was in college, I would receive an email from him asking me for money to pay his medical bills.

But as a nine-year-old in 1997, all I knew was that my father was gone, that we had to move out of our home, and that, for some reason, most of our belongings were to be sold. Goodbye to the wooden staircase, the pink bathtub, the terracotta roof. Goodbye to the floral couch, the ixora bushes, the red plastic car I pushed around the garden. We visited once after everything had been cleared out, before the banks took it. I walked through that empty house, touching each wall and drawer, full of a feeling I couldn’t name that threatened to burst out of me at every turn. From my mother’s trembling voice, her lips pressed tight, I knew it was crucial that I show no sign of this. So I pushed it deep down and walked through the house as if it were nothing at all.

It is a lesson many of us learn eventually, I suppose—that a seemingly solid life can disappear in an instant. Misfortune, sickness, the death of a loved one all come sooner or later; no one is immune. Still, I mourn having learned this lesson so young. To be homeless and fatherless in a flash, bankrupt, adrift—still, my brain interjects at this point, there was no war, no violence or abuse, my mother remained, we had lost our home but we were not without shelter when we were taken in by relatives, et cetera et cetera. Not that bad. So goes the mantra of survival. Our minds can bend reality, if only we try hard enough.

Our second home, if you could call it that, was the living room in the small flat of an aunt. Thus began my years of sleeping on the floor. I did not feel it as a hardship. At nine, sleeping on the floor seemed fun, like camping, though I had never been camping.

I remember little about my aunt’s flat. When I think back on this time, I think of the slice of apple my mother had told me to eat that I secretly threw out the window. The next day, my aunt found it in the common corridor outside the front door, shriveled and brown, beset by ants. I remember the hot slick of shame as I lied that I had no idea how it got there. I was punished nonetheless, made to stand in a corner in this unfamiliar place, reflecting on my crime.

Our third home was the spare bedroom in my grandmother’s even smaller flat. Into this bedroom my mother moved the few belongings we had kept from our old life. My parents’ bed. The low white dresser and floor pillow, where my mother sat to put on make-up each morning. To that she added a set of plastic drawers that I’d never seen before to store our clothes, and a dining chair from the living room, on which she placed a small fan. She and my brother shared the bed, while I slept on a thin mattress at its foot that we propped up against the wall each morning so that there was space to walk. The mattress was stuffed with coconut husk, and lying on it, I could pretend to be a child in one of the books I’d read—a child on a farm in the English countryside, lying on a bed of hay.

Our bedroom faced a busy main road, and across the road, the elevated MRT tracks. Every five minutes a train would roar past. The trains measured the course of each day, waking us up before dawn, passing through all day, stopping at midnight. My grandmother had the other bedroom, which faced the back of the building, and was quiet but dark. Her room smelled of medicated oil and the musty, unfamiliar scent of her body, smells that filled me, for some reason, with dread. My grandmother spoke Hokkien, no English, and little Mandarin. I did not speak Hokkien and my Mandarin was poor, so we spoke little. I was scolded by her often. Though I remember little of the substance of her scoldings, I remember their tone well: aggrieved and indignant, which at the time I took for dislike, but now I understand to be love.

My grandmother was my mother’s mother. An illiterate woman and single mother herself (my grandfather had been a rag-and-bone man who’d died young after accidentally handling a land mine for scrap metal), she had not approved of my father when they’d first met, despite his education, charm, and higher social class. He was untrustworthy, my mother’s family had thought. There was a particular card game that my mother spoke of, in which her sisters were convinced my father had cheated. Still, my mother had married him. Eventually he’d won them over with his easy charisma and impressive lawyer job. As a child I wasn’t privy to my grandmother’s thoughts when everything fell apart, but I wonder now if she might not have been entirely surprised; if she blamed herself or my mother for not preventing what they saw coming so many years ago.

In addition to the bedrooms in my grandmother’s flat, there was a narrow living room no larger than a parking space and a kitchen in the back.

“Do you mind all this?” my mother asked me often, to which I would shake my head, embarrassed by the shine of her eyes.

It was true that I did not mind most of it. The loss of our home, my own bed, my own space. I remember thinking that adults did not understand at all what children minded and did not mind. I cared little for the material things that my parents thought important. Eventually I would grow to hate material things, to hate money—it was what had cost me my father, after all. At the same time, I would crave it desperately as the seeming solution to all our problems.

The one thing I did mind in my grandmother’s flat was the bathroom. It was a bathroom of the old sort, located at the far end of the kitchen behind a door of thin, clangy metal that latched with a dangling hook. In it there was a hole in the floor, a squat toilet that flushed with a chain. There was also a tap which released cold water into a large, plastic bucket which came up to my waist. In the bucket floated a scoop that we used to splash water on ourselves for showers. It wasn’t the squat toilet or bucket showers that bothered me, but rather the slime and rust that collected in every crevice. Singapore, land of eternal summer and hundred percent humidity, has always been a fertile environment for mosses, fungi, mosquitoes, beetles, lizards. Nowhere was that clearer to me than in my grandmother’s bathroom. I took my showers on tiptoe, trying to minimize the contact my feet had with the slimy tiles and black mold that coated the grout. I did my best not to look at the divot in a pipe close to the ground, filled almost entirely with deep green algae that was always wet and shining, on which houseflies perched. When squatting over the toilet to pee, my face would come uncomfortably close to that pipe, that frightening, slime-filled divot. Then there was the chain of the flush, caked with brown rust and seemingly always wet, that I pulled on as lightly as possible.

And yet I lingered in that bathroom. I spent hours behind the metal door, pouring tepid water over my naked body, long after I’d gotten clean. I’d developed a habit of staying in bathrooms by myself. At school, too, I spent the hour between the bus dropping me off and the morning assembly bell sitting in a cubicle in the girl’s bathroom. Sometimes I read. Mostly I did nothing at all. I was waiting, perfecting the skill of waiting. Years later, I see that I was waiting for something to change, to lift me out of the life that I still believed was temporary. Still, someone always knocked on the metal door. The school bell always rang. And I was plunged into my unchanged life again.

My fourth home was a three-bedroom flat located away from the MRT tracks with a regular commode toilet. Now my mother and grandmother each had their own rooms, with my brother and I in the third. We squeezed in two single beds, a desk, a bookcase, a small plastic chest of drawers. Each item of furniture was a Tetris piece, carefully fitted into place. Going between the beds required one to turn sideways and walk like a crab; to pull out a chair at the desk, you had to push the beds back. It still felt like luxury. It was ours, and I was no longer sleeping on the floor.

I would stay in that room, comforted by my brother’s loud snores, until I was eighteen and left for college in America. Though I spent half of my life up until then in that flat, I never thought of it as home. My mother, with her high school diploma and scant work experience, had taken a job as a receptionist at a clinic, and was making eight hundred dollars a month. The only reason we’d been able to move into that modest flat was that it had been bought by her boyfriend, an elderly man who smelled like my grandmother and lectured me about Christianity, whom I was told to call Uncle.

He was no uncle of mine, I thought, and this flat no home of mine. Those were the years I stopped waiting and committed myself to escape. I would depend on no one. No father, no family, certainly no man. Our minds could bend reality, if only we tried hard enough. I had been a good student up until then, but with some effort, I became an outstanding one, and by the time I graduated high school at eighteen, I had won several highly selective government scholarships to attend college abroad.

My fifth home was Columbia University. A series of dorm rooms with the names of dead people: Carman, Claremont, Wien, Woodbridge. At the end of each academic year, we packed our belongings in boxes and rolled them in plastic bins to the Manhattan Mini Storage just south of Morningside Park. Despite the temporariness of rooms, in New York I found a freedom and peace I had not felt for many years. I discovered that comforting cliché that has for centuries buoyed millions of errant souls who drift into the city’s vibrant, crushing vortex: here, I could be nobody, I could be anybody. I didn’t have to be fatherless, drifting, helpless. Home, in fact, meant little in this place where people came and left at the drop of a hat, where eviction was a fact of life and furniture lay brightly on curbs for anyone to take. Who cared if I’d once been a girl in my father’s arms, lowered gently into a pink enamel bathtub filled with iodine water? Everyone in this city had their own tragedies, mine but a paltry, privileged one in comparison.

One December morning, in the cold winter light of my senior year dorm room, I received an email. It was from a woman who said she was my father’s girlfriend. He was in hospital, she said, very sick and possibly dying.

I had received sporadic emails from my father over the years, wishing me happy birthday, congratulating me on my exam results, so stellar they had been publicized by the school online. Letters too, scrawled longhand on crumpled foolscap paper that came from a prison in Thailand. They arrived shortly after we moved into the flat bought by my mother’s boyfriend, and at first, I thought I should respond to them. But I found I did not know what to say, how to conduct a relationship with this fugitive man who claimed to have been undone by anyone but himself—the fake passport peddler who stole his money, the law firm partners who forced him to run, the relatives who wouldn’t help. Why he was in Thai prison was unclear; something to do with someone who had let him down, yet again. I had no idea, either, how to respond to his questions about school and friends and extracurricular activities. What was I to say to this father I knew and did not know, loved and despaired over, a remnant of a life I was trying to accept was truly over? It was easier not to respond, and beset by heavy guilt, I was silent. Still the emails kept coming, spottily, over the years. Happy birthday. Happy birthday to your brother. Congratulations on graduating. Congratulations on going to college.

Later, the emails got more fantastical. He wrote that he had taught himself Thai and Malay, and claimed to have escaped from prison by gaining the trust of the warden, who used him as a translator in court, and had one day left him unattended in the car on their way to a hearing. I opened the door and walked away. Of course, they said that I did all kinds of things. Beat him up, left him for dead by the roadside. But the reality was I opened the door and walked away.

Based on what I knew of my father, it was both believable and entirely not. Perhaps, thinking he was really going to die, he wanted to unburden it all to me. A convoluted and fantastical tale of the last decade: credit card fraud and casino gangs, the cockroaches that crawled over him as he slept on the floor in his prison cell, stolen cars, drugs. I believe he both exaggerated much and held back the worst of it.

I took up meth. To prove to this woman I was dating that I could start and then give it up. Of course, I couldn’t. Anyway, I stopped in prison. Not that you couldn’t get meth in prison. But it was expensive. I could either spend my money on meth or KFC. I wanted the fried chicken. So I gave up the meth.

Poor genetics aside, that was the reason for his weak heart. I didn’t know how to respond to any of this, and now, he was going to die. In my empty dorm—everyone had left for the winter break—I cried. How I cried—huge, terrible sobs, the kind I had not allowed myself since he first left. The years between then and now seemed never to have passed at all. I found myself thinking, like a child, over and over: I want to go home. I want to go home, I want to go home, I want to go home.

But where was home? Not New York, this anonymous, whirling place, as much of a new start it had offered me. Not my mother’s flat in Singapore, bought and beholden to her boyfriend, crowded with the unhappy bodies of my broken family trying to get on with life. Not my grandmother’s old flat, with its dying smells and moldy bathroom with the thin metal door.

The home I wanted to return to no longer existed. The house still stood, but strangers lived in it, hung their clothes in its wardrobes, sat in the shade of its small patio, opened and closed its windows each day and night. Wooden steps, pink bathtub, terracotta tiles—they were still there, but my family was gone, and our old life, never to return.

My father did not die then. He recovered from his surgery and lived another seven years in a remote Thai town, teaching English to young children. From the comments on his Facebook page, I gathered that he was a good teacher, and that his students loved him. His father, who’d died before I was born, had been an English teacher in Singapore too, and a decade later, after a winding road to becoming a novelist, I too would become a professor of English, teaching fiction writing at an American university.

After graduating, I moved to London for the government job that my college scholarship required me to do. Now I obsessed eternally about money. Earning it, saving it, investing it. Most of all, I loved having it in my bank account, sitting there and doing nothing at all. Though I had an almost obscenely well-paying job in private equity, working for the government’s sovereign wealth fund, I spent almost nothing day to day. I rented a moldy studio on the fourth floor of a walk up, with slanted, broken floors and windows that wouldn’t close. For lunch, I ate £1 bags of salad greens with nothing but the olive oil in my office’s communal pantry. I walked to save money on the tube fare. I continued to live the way I had learned to live growing up, as if I had nothing, as if all was temporary.

$23.80

amazon.com

Unexpectedly, all this and other frugalities allowed my boyfriend and I to buy our first apartment when I was twenty-six. It frightened me to buy something with him, to use up my hard-earned savings, but I put down two-thirds of the deposit, secretly glad to be the majority owner and thus safe if anything were to happen. I didn’t know what I thought would happen. Tragedy, I supposed; financial ruin of some kind. This way, I was not beholden to my boyfriend, and could afford to keep my own home if he were to go bankrupt or leave.

Happily, we painted it, bought IKEA bookcases, and decorated with plants. I had been with my boyfriend since our sophomore year of college. The life we were making together, in spite of myself, made me feel like I had a home again. Each day that we returned to our apartment and it was still there, each time I received a mortgage statement with the balance inching down, each night we fell asleep with our limbs gently intertwined beneath the covers, I felt the ground slowly solidifying beneath me.

The flats I’d called home after my father left were heavily subsidized public housing units in which many Singaporeans live. The government had the right to take back these flats—to knock them down and rebuild at their discretion. In the years that I was away at college, my grandmother’s flat by the train tracks was torn down by and replaced with newer, taller buildings. My mother’s flat, too, was requisitioned, and my family was made to move some streets over. For a long time, our old flat remained empty.

“I don’t know what they’re doing with them,” my mother said. “I’m sure they have a plan. Some science park or office building. Or maybe an extension of the university.”

But the years went by and the empty blocks remained. The entire estate would be dark when we drove by at night—a strange sight in densely populated, brightly lit Singapore. By day, stray cats roamed the void decks, and waxy grass grew tall between infrequent cuttings. Whenever I walked past, I thought of the empty rooms of my mother’s flat, the place that had always felt borrowed, beholden as it was to the strange man who was not my uncle. Still, it was the home in which I had spent the longest time, in which I’d grown up nonetheless.

One time, walking by, I noticed the window of my old bedroom was open, though the flats were still empty. I was struck by sudden worry that it was I who’d left it ajar, and my mother’s old admonishment about letting the rain in sprung to mind. Rain in Singapore, when it comes, is sudden and torrential, and on more than one occasion we’d returned home to realize we hadn’t closed a window, finding the floor flooded and the beds soaked through.

I had the urge to go into the flat and shut it. But I no longer had the keys, of course, and the flats were government property now, off limits to trespassers. So I stayed there on the ground floor, looking up at our old flat. Above, the window stayed open, dark and implacable as my dreams.

It was my father’s heart that killed him in the end. A few years later, after my boyfriend and I had just gotten married, after I’d quit my job and we moved to Texas for me to start a graduate program, the call came from his girlfriend, the same woman who’d emailed me out of the blue that first time. Again, he was very sick, in surgery.

My husband was away on a work trip, so I was alone in our new apartment when the next message from his girlfriend came the following day. The surgery had not gone well. He was in a coma now, she said. Are you coming? You should come. She gave me the name of the town, what airport I should fly to, what bus to take to get there.

I did not go. It would take me over thirty-five hours to make the trip from Austin, and I was afraid that I would get there to find that he had died. I did not think I could bear it, being alone in a strange place with my dead, fugitive father, whom I loved and missed so dearly, but had not known for decades.

We’d come to Austin with two suitcases, leaving our comfortable life in London behind. On the move again, we didn’t have American bank accounts yet, and we were on prepaid cell phone plans because we had no credit scores. In our empty rental apartment, there was a futon, some IKEA Billy bookcases, and an elderly cat, recently adopted. That was where I was when I woke up on the morning of November 2nd, 2017, to read the message saying that my father had died. He’d never woken from his coma and gradually, his body had shut down.

Grief: an impossible thing to describe to anyone who has never felt it, and all-too familiar to anyone who has. It slams into you like a wave, deafening and bone-shattering all at once. Takes the air from your lungs, the warmth from your hands, the steady rhythm from your stupid chest.

And again, here was that thought: I want to go home. What was I doing in this empty apartment under the blinding blue Texan sky? But that was that. My father was dead in a distant town, at the end of a life I knew almost nothing about. Any final illusions I had harbored, deep down, of the tragedy that was my family being resolved were obliterated. A part of me had still believed, like a child, that my father was Henry Sugar. That he would one day return to Singapore redeemed, reality made whole by the force of his will. That it would mean that I could return too; that home would be home again.

A few years after my father died, I visited my mother in Singapore. We drove past where our old flat, the one her then-boyfriend had bought, should have been. But all that remained now was empty space.

“Oh, you didn’t know?” my mother said. “They knocked them down a while ago. Who knows what they’re going to do with the land.”

We stopped the car, got out, and walked up the slope I used to walk every day when coming home from school. All that remained now was an enormous field of grass. The blocks must have been demolished some time ago, as my mother said, because the grass had grown so thick and green that you’d never have known there’d been buildings here at all. I thought of the bathroom in my grandmother’s flat, teeming with a similar green. In our hot, humid land, space was so quickly filled by all manner of living, creeping things, needing little more than light and air, determined to grow nonetheless. Even the buildings came and went, jostling for survival, no more permanent than the algae that bloomed after heavy rainfall and dried up under the next day’s scorching sun.

I tried to find the place in the grass where our flat had once stood. Where my bed might have been placed, where I might have sat, reading my father’s letters and emails and not knowing what to think. Then, I noticed the trees that remained. They had once lined the sidewalks that ran between each block, their broad, whispering canopies offering relief on especially hot days. Now, with everything gone, the trees were still in neat rows, forming a ghostly outline of where the buildings had once been, tracing the invisible shape of all the vanished lives that had crowded that place.

Following the trees, I found where I thought our flat might have been. I stood there in that rare empty space, looking up. Something would come along soon to fill it, I knew, but for now there was just this: my small, enduring self, the grass, the trees, the bright and unending sky.

You Might Also Like