The Day a Wild Stallion Tried to Kill My Horses on the Pony Express Trail

This article originally appeared on Outside

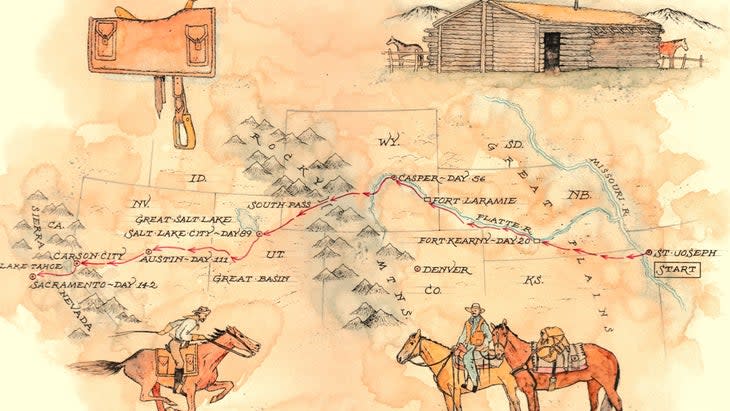

In May 2019, I set out from St. Joseph, Missouri, with two horses and a plan to ride 2,000 miles to Sacramento, California, along the Pony Express Trail. My book, The Last Ride of the Pony Express, is the story of what I saw, who I met, and what happened. I undertook the journey as a large-scale exercise in horsemanship. I wanted a boots-on-the-ground understanding of the famed Pony Express mail service. I also wanted to make a transect of the cultural West. I wanted to meet the people and learn about their lives in all the places along the trail that I'd never been to. The adapted excerpt below is an encounter I had in the desert southwest of Salt Lake City, Utah. I had been traveling for 92 days.

I watched the roan horse wallow in a mudhole a mile below me. You wouldn't have thought that amid all that wind and sky and rock of Utah's West Desert there'd be water enough to make a mudhole, but there in front of me on a yellow plain that seared under a high sun, the dusky horse flopped from side to side, kicking its legs in the air like a dog scratching fleas. The horse's solitude told me it was a stallion. Four hundred wild horses, known as the Onaqui herd, summer in this valley, and the only ones that range alone are mares about to foal, old horses about to die, and stallions without harems of mares.

This horse didn't look old and wild mares don't foal in August, so I assumed he was a stallion. He stood from rolling, and when he walked out of the mud, he appeared a much darker horse. He hadn't seen me and my two horses-- Chicken Fry and Badger--enter the valley from the east, but I figured it was only a matter of time.

Wild stallions will kill a domestic gelding, a castrated horse, in the same way that wolves will kill a domestic dog.

Chicken Fry and Badger showed no signs of agitation, but why would they? For the past three months, we'd been traveling west on rural roads, past farms and ranches and suburban subdivisions, and they'd seen many horses. But those horses posed no threat; they were domesticated. This one was different.

This was a wild horse, a mustang, a free-roaming member of feral equines that became part of the Western landscape after sixteenth-century Spanish conquistadors brought the first horses North America had seen since the last ice age, ten thousand years ago. The Spanish, and countless others since, lost horses that stampeded to freedom in the middle of the night or wandered off in search of fresh grass or otherwise untethered themselves from their owners. Those strays gathered in herds and became known as mestenos (Spanish for "escaped livestock"). The word was later anglicized into "mustang," and today it's a common term for a wild horse of the American West.

Over the centuries, one enduring trait of wild horses has been they're aptitude to harass domestic horses. The roan mustang before me posed a problem because I wanted to camp at a corral beside the mudhole that he'd just rolled in. That corral was the only safe haven for my horses for a day's ride in any direction.

Wild stallions will kill a domestic gelding, a castrated horse, in the same way that wolves will kill a domestic dog. Chicken Fry and Badger, therefore, were vulnerable. Mares may be absorbed into a harem, but geldings are a threat. And since domestic geldings rarely mature with the sparring and fighting that establishes social hierarchy within a wild herd, Chicken Fry and Badger would likely not last long.

They'd also be wearing their saddles and carrying my gear--trappings of domestication that would hinder their survival. I was more than halfway up the Pony Express Trail--92 days and more than a thousand miles out from its eastern terminus in St. Joseph, Missouri--and I hadn't come this far just to lose my horses in a running fight with a mustang stallion.

So I decided to take a nap. Better to do nothing and potentially avoid a wreck than walk right into one. I figured the situation might work itself out, that after an hour's doze the stallion would be gone. As I unlashed the panniers from the packsaddle, slid the bridle off Badger, and loosened the cinches on the saddles, both horses sighed with the prospect of a reprieve. I leaned against a tree and ran the lead ropes under my legs so that I could feel any sudden movement they made.

When I lifted my hat from my eyes an hour or so later, three mustangs stood on the plain. An old white horse with a swayed back, a black horse, beyond the white, that waved in mirage like a candleflame, and, nearest to us, the roan. The area around the mudhole had become a bachelor boneyard, and I could have listed things I would rather have seen.

I asked Chicken Fry and Badger if they had any ideas about scattering the congregation, but they only yawned and stretched like soldiers waking from a halt. So I came up with one: I would throw rocks. Rocks the size of lemons or baseballs. I'd wait to throw them until I could see the whites of the stallion's eyes.

I carried a lightweight .357 revolver in case I needed to humanely put down one of my horses due to some catastrophic injury, and I took the pistol from my saddlebag and slid it into my vest pocket. I didn't know what I would do with the gun--maybe shoot the ground in front of the roan-- but if I did that, Badger, sensitive as he was, would probably jerk the reins from my hands and take off across the desert. Which would leave me down a horse and in a world of trouble, assuming I could still hang on to Chicken Fry.

I readied my horses and hardened up the cinches on both saddles tighter than if there had been no mustangs in my future. I stepped onto Badger, and eased downhill into the furnace of an August afternoon. When I was halfway to the corral, the roan horse saw us. He jerked up his head from grazing, and I cursed him. He took a few halting steps, broke into a trot, and pretty soon headed our way at a run.

I slid from the saddle and informed Chicken Fry and Badger that we were about to have our first scrape with a mustang. The roan stallion made quick work of the distance between us, and when he was a hundred yards off, he vectored to the right, hammering over the dry plain on black hooves that looked and sounded as hard as the basalt cobbles beneath him. He arched his neck and swung his head in bold communication, and his posturing was not lost on me.

The author spent a lot of time singing to his horses on the trail. Check out this video.

Video loading...

He was a large horse, the color of rust, with a black mane and tail, and his head was dark and unrefined. Old scars on his back showed as gnarled lines and crescent moons--haired-over glyphs from that hierarchical herd sorting that betrayed him to be no colt, but a mature horse. The tops of his legs had the horizontal striping of ancient equine DNA, and though I knew he carried the distant pedigree of a domestic horse, he looked as raw and wild as the desert that made him.

I might as well have been camped on the African savanna with lions and leopards. The mustangs felt just as dangerous.

He wheeled a full circle around us at a gallop. In one hand, I held the reins to Badger and the lead rope to Chicken Fry, and had a rock in the other as he came in front of us, some forty feet off. I missed with my first rock. The second hit him at the base of his neck, and he shied violently, leaping forward into the air and pawing at the rock that had just invaded his space. I landed another rock in his flank, and he bucked, kicked his hindquarters straight out with a snap of hooves and muscle that looked like he might kick the door off heaven, and then he took off at a flat run in the other direction.

He charged another circle around us, but this time he appeared frustrated. He stopped square in front of us, again some forty feet off, looking right at me with his head held high and his nostrils flaring, and I figured that this was my chance to put one between his eyes, but I missed. The rock flew wide to his left, and he dodged right and disengaged, quartering away from us at a walk.

Chicken Fry and Badger were unfazed, and had stood quietly behind me while I held our ground. I filled my pockets with more rocks. Once the roan was about one hundred yards away, he lowered his head to graze. But he was not disinterested; I could see the insides of his ears. His ears turned toward us told me that we held his focus as I made for the corral afoot, leading Chicken Fry and Badger so that if the stallion made another run for us, I'd be ready.

I'd known there would be wild horses in western Utah. I'd known that wild horses would be a fixture of the range between the Rocky Mountains and Sierra Nevada. But I hadn't anticipated the acute threat they would pose to my horses. I might as well have been camped on the African savanna with lions and leopards. The mustangs felt just as dangerous.

For the past three months I'd seen the color of the West in shades of people and land and circumstance. I was passing through a continental theater where I found too little rainfall, too much of the original prairie broken up by the iron plow, too many old timers who remember heavy-snow winters like they don't get any more. I found too many invasive species, too much irrigation draining dwindling aquifers, too many small towns ready to fall off the map.

But what I found at the mudhole three days into the desert was different, more unsettling. Wild horses represent and signify a variety of rangeland aspects, but on that August afternoon, the roan stallion at Simpson Springs conveyed to me that the undiminished wildness of the West could be dangerous--beautiful and intriguing, but dangerous--and that not everything had changed since the days of the Pony Express.

To find out what happens next, get a copy of The Last Ride of the Pony Express, the author’s first book. Grant began at Outside as a fact checker in 2010. Since then, he's written numerous stories for the magazine involving horses, including a horse race across Mongolia, an expedition to find gold in Arizona, and a 400-mile ride across Wyoming. He currently lives on a farm outside Santa Fe, New Mexico, with his partner, Claire, five horses, three chickens, and two dogs.

For exclusive access to all of our fitness, gear, adventure, and travel stories, plus discounts on trips, events, and gear, sign up for Outside+ today.