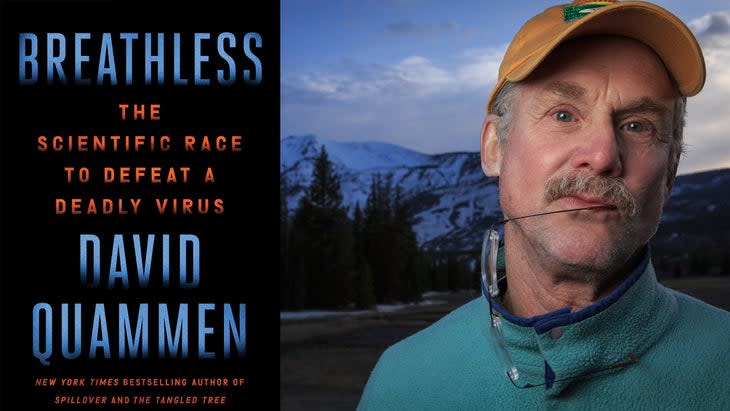

David Quammen’s ‘Breathless’ Is a Riveting Account of the Race to Understand SARS-CoV-2

This article originally appeared on Outside

Editor's note: Outside will be hosting a live Q&A with David Quammen on Thursday, October 13, at 6 P.M. Mountain Time. Join us on Zoom by registering here.

In March 2020, I was busy devouring The End of October, a novel by Lawrence Wright about a deadly new virus that shuts down the globe as epidemiologists engage in a frantic race to isolate the pathogen. That plot, of course, was also playing out in real life at that very moment. Nearly three years later, we have a compelling new nonfiction scientific thriller about SARS-CoV-2: Breathless: The Scientific Race to Defeat a Deadly Virus by science writer David Quammen.

The book is already a finalist for the National Book Award, and for longtime Outside readers, it's something of a dream come true (even though it's about a nightmare). With more than four decades of reporting on the natural world under his belt--starting as Outside's Natural Acts columnist in 1981--Quammen was perfectly placed to listen in on the conversation as scientists and virologists began rapid-fire pinging each other in December 2019--at first with rumors of an unidentified pathogen, and then with snippets of genetic code--trying to get a bead on something that, said one, looked "very, very similar to a SARS coronavirus."

The emergence of a "novel" virus was, of course, a surprise to none of them. As Quammen wrote in 2012 in his similarly terrifying book Spillover, infectious disease scientists have been warning for years about the very real possibility of a pandemic caused by a virus "spilling over" from the nonhuman world. That's what caused AIDs, Ebola, Marburg, MERS, Nipah, West Nile, and others serious maladies that Quammen chronicled in in the book. (The main lesson I took from Spillover: never, ever go anywhere near a bat cave.)

In Breathless, Quammen writes that virologists "had for decades seen such an event coming, like a small, dark dot on the horizon of western Nebraska, rumbling toward us at indeterminable speed and with indeterminable force, like a runaway chicken truck or an eighteen-wheeler loaded with rolled steel."

That's the third line of the book. It only gets crazier from there.

Quammen would probably disagree with describing Breathless as a thriller. "This is a book about the science of SARS-CoV-2," he writes. "The medical crisis of COVID-19, the heroism of health care workers and other people performing essential services, the unjustly distributed human suffering, and the egregious political malfeasance that made it all worse--those are topics for other books." (For those stories, try The Premonition, by Michael Lewis, or The Plague Year, by Lawrence Wright.)

Quammen writes clearly, accurately, and even conversationally about the science, from the nomenclature conventions of virus variants to a virus's "receptor binding domains." One of the COVID-19 virus's most nefarious adaptations is something called a furin cleavage site, which signals the infamous spike protein to change shape, as Quammen puts it, "like a Transformer robot metamorphosing suddenly into a truck."

As Quammen warns us at times, the scientific going can get tough--some of the explanations are very technical. But just when your eyes glaze over, he is there to gently shake you awake. At one point, after I'd zoned out reading a calculation for herd immunity ("threshold = 1 - 1/R0,"), he began the next paragraph with the words: "He prints equation. Eyes roll back in heads. But no, wait, look how easy this is."

He demonizes no animal, not even the horseshoe bat from which SARS-CoV-2 likely emerged, nor the critically endangered pangolin, a group of whom died in a Chinese wildlife rescue center of an unknown respiratory disease, "inactive and sobbing."

One of the best things about Breathless is Quammen's familiarity with the remote areas where viruses tend to emerge. His beat, after all, has always been the wild. He has traveled with disease cowboys, as they're sometimes called, into caves and around remote villages, looking for viral hosts. He has seen the crowded markets full of palm civets, pangolins, and raccoon dogs, with "multiple animals packed into small cages, stacked atop one another, sharing their fears and their bodily fluids, while hundreds of people worked and lived and ate amid the jumble, toddlers ran back and forth amid offal from butchered animals, [and] families slept in cramped lofts above their shops."

That global experience gives him compassion for countries where virus spillovers tend to happen, and sympathy for world leaders angry that Americans are getting fourth and fifth shots while many low-income countries have had none. He demonizes no animal, not even the horseshoe bat from which SARS-CoV-2 likely emerged, nor the critically endangered pangolin, a group of whom died in a wildlife rescue center of an unknown respiratory disease, "inactive and sobbing." Even viruses themselves get their due. They are like fire, he writes, "the dark angels of evolution, terrific and terrible," without which "the immense biological diversity gracing our planet would collapse like a beautiful wooden house with every nail abruptly removed."

The heart of the book is a meticulous investigation into the origins of SARS-CoV-2, and Quammen turns over every stone. In what will likely be the most provocative part of the book, he spends serious time examining and debunking the theory, ultimately rejected by scientists, that SARS-CoV-2, escaped from a lab.

Likewise, he doesn't merely roll his eyes at the early claims surrounding cures like the anti-parasitic drug ivermectin. Ivermectin, he writes, is a trusted tool among veterinarians and a medicine that won its inventors a Nobel Prize. Very few authors could write the following sentence: "I've taken the stuff myself, in small dosage, when I was walking across swamps and forest in the Republic of the Congo and Gabon, being bitten continually by blackflies, and hoping to avoid river blindness."

It just doesn't work on COVID-19.

Luckily for the easily scared, some of the most unsettling revelations about SARS-CoV-2, are already behind us: the realizations that the virus was airborne and that asymptomatic people could silently spread it; those early CDC tests that didn't work; the long months without effective treatment or vaccine.

And yet, there is still terror to be found in these pages. Breathless introduced me to perhaps the two scariest words in virology: "sylvatic cycle." After the first spillover of a pathogen from the animal kingdom to humans, humans can then infect pets or farm animals, which can then infect wild animals, providing a hiding place for the virus to mutate again. As Quammen writes: "A virus with a sylvatic cycle is two-faced, like a traveling salesman with another wife and more kids in another town."

That is already happening, right here in the United States. During the 2020-2021 hunting season, Iowa wildlife researchers studying chronic wasting disease found SARS-CoV-2 in 82.5 percent of the 97 deer carcasses they tested. The United States, Quammen reminds us, is home to an estimated 25 million white-tailed deer.

This is the world we live in now. "One thing is nearly certain, I believe, amid the swirl of uncertainties," Quammen writes. "COVID-19 won't be our last pandemic of the twenty-first century. It probably won't be our worst."

And it isn't over yet. On October 4, when Breathless was published, the author was at home with COVID-19.

For exclusive access to all of our fitness, gear, adventure, and travel stories, plus discounts on trips, events, and gear, sign up for Outside+ today.