Dashing and Debonair Design: Remembering the Late Paul Fortune

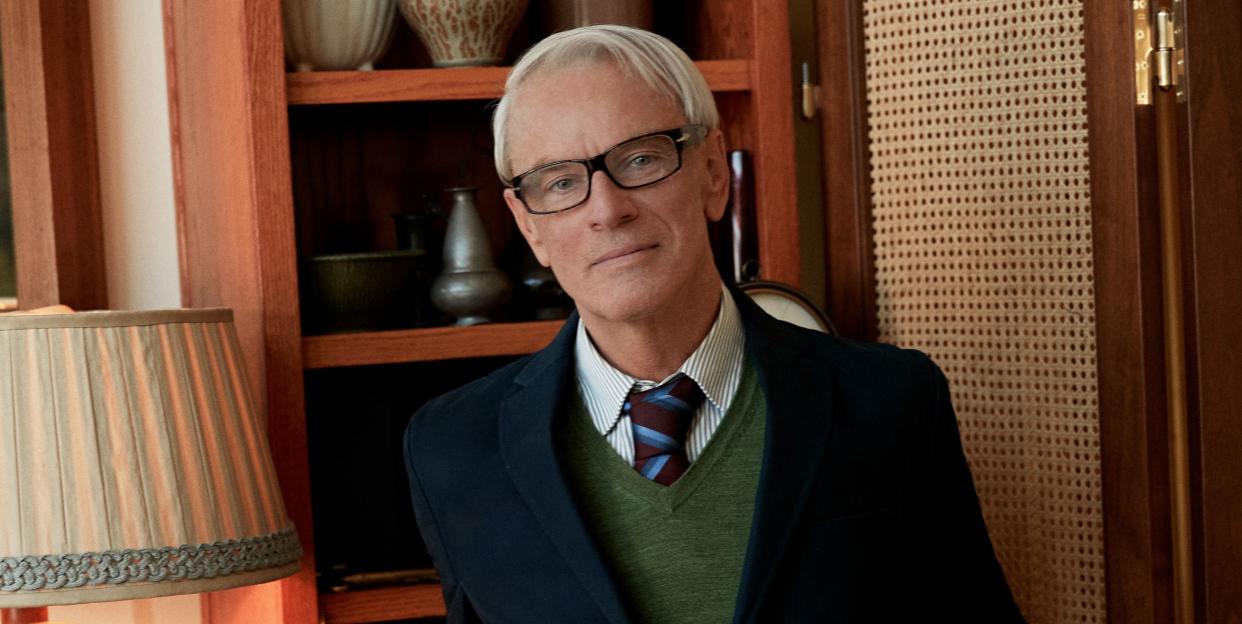

In the world of interiors, Paul Fortune was a cult figure, if not quite a household name. That, like everything about him, was by his own design. The British-born decorator, who passed away on June 15 at the age of 69 at his home in Ojai, California, eschewed social media. He kept a low profile, moving several years ago from his longtime home in Laurel Canyon—the elegant, atmospheric setting where he entertained friends like Rupert Everett, Angie Bowie, Marc Jacobs, and Marisa Berenson—to drop out in the lush hills north of Los Angeles with his longtime companion, ceramist Chris Brock. The ploy backfired. “He tried to disappear, but that only made him more in demand,” says his friend, the designer David Netto. “The more he tried to make himself obscure, the more people were beating a path to his door.”

I met Paul in the mid-1990s, when I worked at Condé Nast’s House & Garden magazine, where he was a contributing editor (and the personal designer to the company’s then–editorial director, James Truman). I had just arrived at the magazine when Paul was assigned to style a story on rectangular glass vessels. In a world of unlimited budgets for sets and flowers, Paul—dapper, with a dry sense of humor and a passing resemblance to David Bowie—ordered a crate of oranges, stacking the fruit into towers and the glass vases into geometric rows. “It’s all about the oranges, isn’t it?” Truman remarked of the simple but genius gesture. Like everything Paul did, the understatement conveyed a perfect sense of cool.

As a designer, Paul put the first vintage Cadillac through the facade of the Hard Rock Café and designed homes for Marc Jacobs, Eileen Getty, Sofia Coppola, and many others. When clients purchased Wilt Chamberlain’s 1970s Bel Air bachelor pad Ursa Major, he jettisoned the pink velvet–lined orgy room but preserved the retractable ceiling above the master bed. Along the way, he appeared in two movies (Sofia Coppola’s Marie Antoinette, as Duc Fortune, and Spike Jonze’s Adaptation), designed music videos and an album cover for the Eurythmics, created a line of Lucite cactus lamps and hand-painted cowskin rugs, and had a hand in two iconic L.A. nightclubs—the Fake Club of the early 1980s, in an old Trailways bus depot, and, with Michele Lamy, Les Deux Café, for which he moved an Arts and Crafts house across the street to create the kind of venue where his friend Joni Mitchell might show up for an impromptu late-night jam session.

Simon Doonan, the author and former creative ambassador at large of the late New York department store Barneys, met Paul in the late 1970s in Los Angeles. “I went to Maxfield, and this friend said, ‘You have to meet Paul Fortune—he is English too,’ ” Doonan says. “Although we were about the same age and only in our 20s, he was bizarrely sophisticated, whereas I was still quite feral and very punk rock. I remember going to his home and watching him effortlessly make boeuf bourguignonne for 25 people. And he brought that same sense of effortless ease to his interiors. He really invented that soigné, eclectic style.”

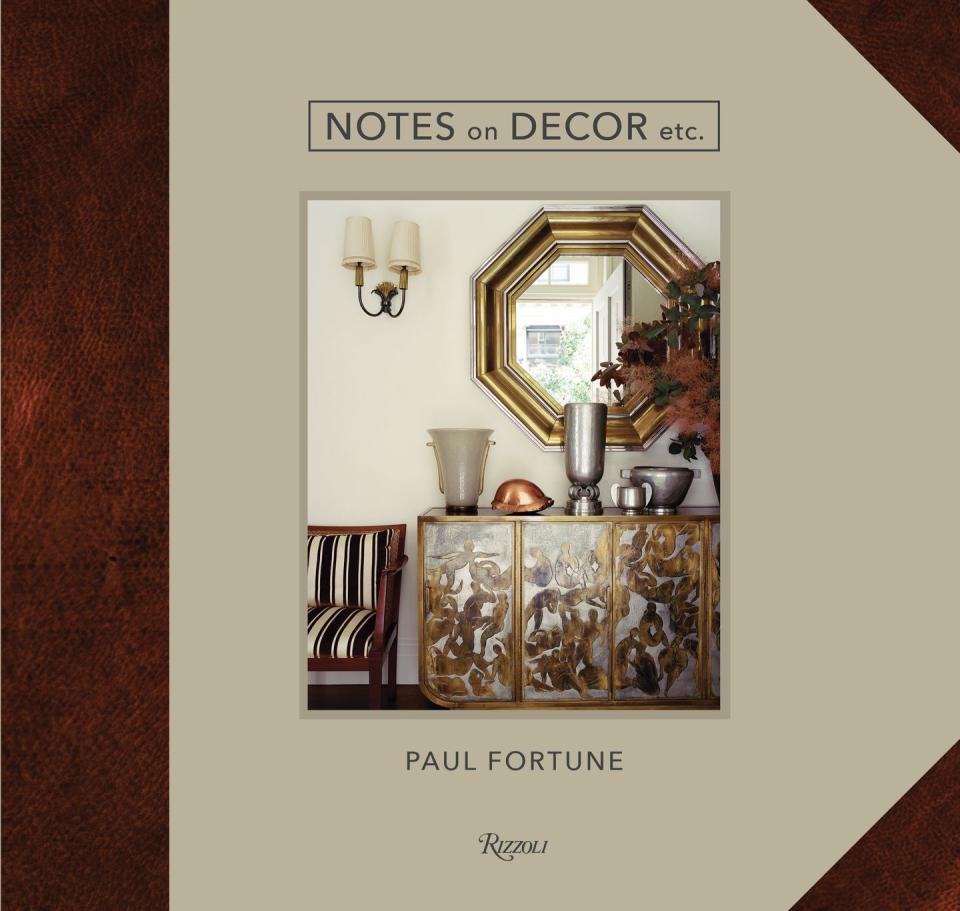

A Paul Fortune room was filled with dark wood and vintage furnishings, upholstered in leather or subdued stripes, and dimly lit (“Spotlights are the devil’s work,” he would say). His own home in Laurel Canyon—which he documented in his 2018 book for Rizzoli, Notes on Decor, Etc. (an opinionated tome that reads more like an autobiography than designer tips)—was “a laboratory for his evolving ideas on lighting and atmosphere,” Netto says. The ELLE Decor A-List designer was so taken with Fortune’s work that he hired him to codesign his Richard Neutra house in L.A. “People thought it was career suicide, but to me he was more than a decorator. Right now, I’m standing in a room he painted red to go with a tartan rug I picked out—which not too many people would have done in a Neutra house. I remember I was in New York when he e-mailed me and told me he had done it, and that ‘It looks really good.’ He was right.”

If anything epitomized Paul’s style, it was his 2005 overhaul of the Sunset Tower Hotel. The space was as subtle as it was urbane—in the lobby, in the Tower Bar, in Bugsy Siegel’s old apartment—a symphony in quiet beige, with pleated lampshade sconces throwing soft light onto white tablecloths and walnut-clad walls framing city views. “You would go there and see Tom Ford, but it was also a place where you could take your mother out for lunch,” Netto says. “L.A. finally had a dining room worthy of a film noir.”

My last full immersion into Paul’s world was on a visit to Ojai with my family in 2018. At dinner, he had my two teenage daughters enthralled with his stories about growing up in postwar England and his early days in the counterculture in New York and Los Angeles. “You knew Warhol, didn’t you?” I asked. “What were you doing in New York?” “Drugs,” was his nonchalant reply, before he regaled us with his memories and contrarian opinions on everything from politics to the AIDS crisis to drag culture and the recent Ojai fires that had forced him and Brock to flee their home. And design, of course.

Later, he wrote an essay for ELLE Decor’s December 2018 issue on his memories of a childhood Christmas in the north of England—one where he convinced his mother to redecorate the drawing room with trendy chairs and wall-to-wall snow-white carpeting, inspired by Hollywood musicals. “For one shining moment, I was digging Christmas,” he recounted. But then the guests arrived, the Scotch was poured, “Aunt Margot missed her drinks table and dropped her punch,” and the festivities got even more rollicking from there. “The carpet was cleaned after the holidays, and the kids were banned from the drawing room,” he wrote. “It became like a joke to us, a weird mausoleum to that last Christmas. Like a Hollywood set, it was only good for one scene.”

As tributes from friends pour in on the social media he hated (“Anyone can Instagram, but not everyone can cast a perfect spell,” he wrote in his book), it is clear that the sui generis Paul Fortune won’t soon be forgotten. “He was life-enhancing, hilarious, generous, and a visionary,” says Doonan, who last saw his friend for lunch in Manhattan in early March, when they shared some laughs and Paul spoke about the renovation of a Frank Lloyd Wright house in Rye, New York, that he was working on for Marc Jacobs. “As confident as he was, he was never a self-promoter,” Doonan observes. “He was always very languid. He would say things like, ‘I’m doing this little hotel.’ Everything with Paul was easy-breezy.”

You Might Also Like